A blog of the Latin America Program

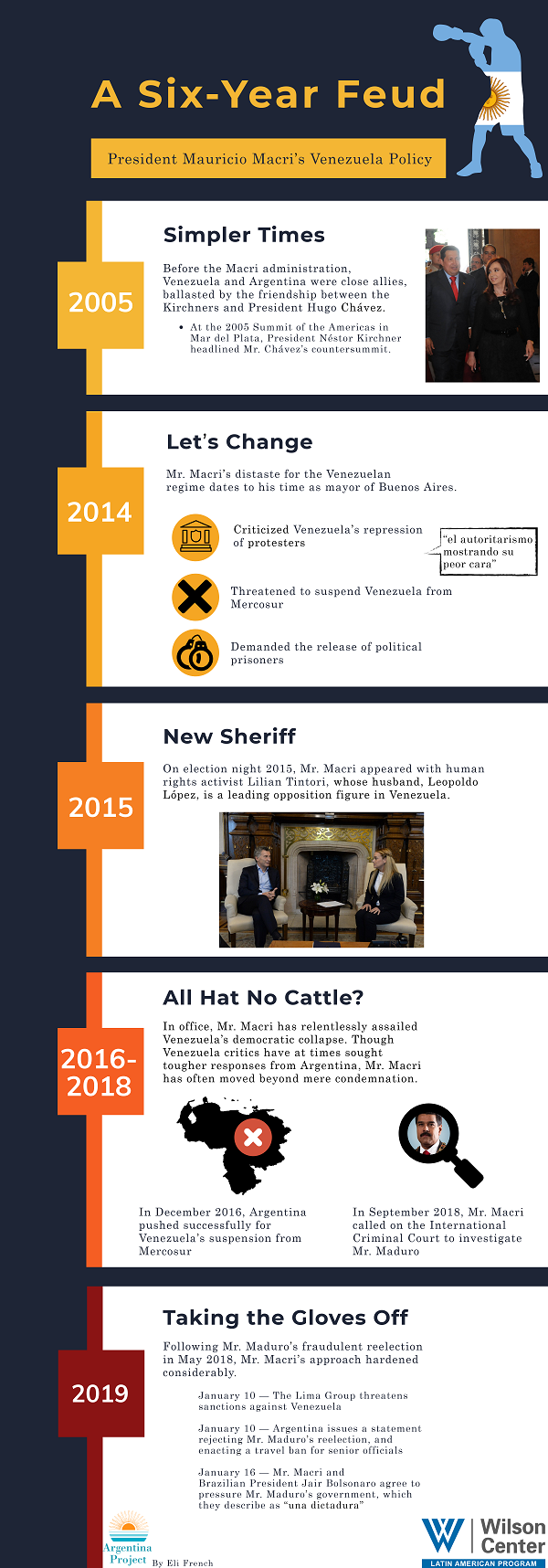

For a decade, Hugo Chávez and the Kirchners were as thick as thieves. At the 2005 Summit of the Americas in Mar del Plata, President Néstor Kirchner headlined Mr. Chávez’s countersummit. Later that year, Mr. Kirchner recognized Venezuela’s friendship, and financing, in a historic speech about Argentina’s multibillion dollar prepayment to the International Monetary Fund – a political masterstroke that unburdened Mr. Kirchner’s government of a “constante vehículo de intromisiones.”

Today, the IMF is back in Buenos Aires and Venezuela is out in the cold.

Since the 2015 election of the center-right Mauricio Macri, Argentina has transformed from a steadfast ally to Caracas’s top antagonist. Mr. Macri is leading a regional effort at the International Criminal Court to prosecute Mr. Maduro – the very same leader to whom Cristina Fernández de Kirchner awarded the Orden del Libertador San Martín in 2013.

Mr. Macri’s critics are unimpressed. Even those who have soured on Mr. Maduro accuse Mr. Macri of cynically piling on only to parrot President Donald Trump’s hard line. After all, at home, Mr. Macri’s human rights record is mixed.

Sure, tightening the screws on Venezuela is a way to win friends on the National Security Council. But Mr. Macri’s distaste for the Venezuelan regime is longstanding. In fact, it predates not only Mr. Trump’s election, but also Mr. Macri’s presidency. As Buenos Aires mayor, he criticized Venezuela’s repression of protestors ( “el autoritarismo mostrando su peor cara”); threatened to suspend Venezuela from Mercosur; and demanded the release of political prisoners. The night of his presidential election, he appeared publicly with human rights activist Lilian Tintori, whose husband, Leopoldo López, is a leading opposition figure in Venezuela.

In office, Mr. Macri has relentlessly assailed Venezuela’s democratic collapse. Admittedly, the Palacio San Martín has not always kept up. Mr. Macri’s first foreign minister, Susana Malcorra, was a candidate for UN secretary general, and she was considered hesitant to alienate Venezuela’s Latin American allies. Nevertheless, under Ms. Malcorra, Argentina elbowed Venezuela out of Mercosur, in late 2016. At the United Nations, Ms. Malcorra’s deputy, Carlos Foradori, explicitly rejected Latin America’s noninterference political culture. (Argentina, he said, adopts the principle of “non-indifference.”) Indeed, in his own UN speech last September, Mr. Macri expressed “una vez más nuestra preocupación por la situación de los derechos humanos en Venezuela,” and he called on the ICC to investigate Mr. Maduro’s misconduct.

Until recently, Argentina’s approach was mostly limited to strident criticism and symbolic acts, such as removing Mr. Chávez’s portrait from the Casa Rosada. But that has begun to change. The latest declaration from the Lima Group not only rejected Mr. Maduro’s reelection, it also threatened sanctions. On January 10, the day of Mr. Maduro’s inauguration, Argentina issued its own statement on Mr. Maduro’s discredited reelection, condemning the “ruptura del orden constitucional”; recognizing the opposition-led congress as the country’s “único órgano democráticamente electo”; and announcing unilateral actions, including a travel ban for senior officials, and steps by Argentina’s financial intelligence unit to limit access to Argentina’s financial system by Venezuelan state-owned enterprises.

After Mr. Macri met with his new Brazilian counterpart on January 16, Ms. Malcorra’s successor, Foreign Minister Jorge Faurie, said the two governments would “defend freedom and the recovery of democracy in Venezuela.”

Love the one you’re with: Back to the base

Populists like Donald Trump and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner count on a hyper-loyal and mobilized base of supporters, even though their radicalism wears on most voters. In the Argentine political lingo, they have “un piso alto, pero un techo bajo.” President Mauricio Macri has opted for the opposite approach; he is usually willing to alienate his base to expand his electoral coalition. For his first two years in office, that strategy was paying off, as Mr. Macri retained his core supporters while literally going door-to-door to win over Peronists.

But as this year’s election approaches, Mr. Macri’s approach looks increasingly risky. In Argentina’s election system, candidates rely upon a highly engaged base to survive the first round of the presidential election, then broaden their appeal in the head-to-head contest. The question is whether Mr. Macri will get a shot at the ballotage, when he would presumably enjoy the fruits of his big tent politicking. After all, his economic management and decision to tackle divisive social issues have disappointed his conservative base, raising the grim possibility of a first round defeat.

Macri voters are considered more conservative and wealthier than supporters of his leftist predecessor, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. Indeed, Mr. Macri finds his base among older Argentines (32 percentage point advantage over Ms. Fernández de Kirchner, according to Poliarquía); residents of the capital city (20 percentage point advantage); and in the interior (16 percentage point advantage).

Last year was rough for Mr. Macri’s base, and his policy priorities have often been unkind to his core supporters. In December 2017, for example, he successfully pushed pension reforms that alienated older voters. Next, he gave the green light for a divisive congressional debate on abortion rights. That legislation passed in the Lower House, but failed in the Senate. Still, the issue provoked one of the most fractious debates in modern Argentine history. It also divided Mr. Macri’s Cambiemos coalition, with a narrow majority of coalition lawmakers voting against it. Over all, voters were split nearly evenly on the issue, but 57 percent of Mr. Macri’s core supporters opposed legalization, according to IPSOS.

That said, in the land of the asado, Mr. Macri has offered some red meat to his base. In particular, he has consistently favored expanded police powers, including greater authority to use deadly force. He has also given a platform to Patricia Bullrich, the security minister widely admired by Mr. Macri’s base. Indeed, her controversial policy change regarding the rules of engagement for police, pleased 84 percent of Macri’s supporters, according to Poliarquía. However, it is not yet clear whether Mr. Macri has struck the right balance between courting poor and working-class Peronists and restoring the enthusiasm of the voters whose exhaustion with Ms. Fernández de Kirchner led them to take a chance on a longshot third party candidate in 2015.

Three years later, Ms. Fernández de Kirchner remains a lightning rod. Widespread anger at the former president has not dissipated – an enduring advantage for Mr. Macri. But admiration for Ms. Fernández de Kirchner among her base has also endured. Ms. Fernández de Kirchner has retained the support of one-third of voters, despite a remarkable pileup of corruption charges. That gives her a strong chance of making it to the second round of this year’s election (though it is unlikely she retakes the presidency).

What about Mr. Macri? His supporters are unlikely to defect to Ms. Fernández de Kirchner. But they are potentially at play. They have seen the economy stumble; pro-market reforms – such as a labor code overhaul – repeatedly falter; and unpopular legislation, such as pension reform, become law. That has created an opportunity for opponents on the center-left, including traditional Peronists such as Sergio Massa and Juan Manuel Urtubey, and on the far-right, such as a Bolsonaro impersonator from Salta, Alfredo Olmedo. That helps explain why, after three years of poaching Peronists, Mr. Macri is turning his attention to voters still waving their yellow balloons.

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Argentina Project

The Argentina Project is the premier institution for policy-relevant research on politics and economics in Argentina. Read more

Explore More in Weekly Asado

Browse Weekly Asado

Dengue Haunts South America’s Summers

Lessons from Costa Rica’s Economic Transformation

Women and Latin America’s Digital Revolution