This is a co-publication with the National Security Archive at The George Washington University.

The Jupiter Missiles and the Endgame of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Part II

Sealing the Deal with Italy and Turkey

Reluctant Turkish Military Needed Special Incentives to Cooperate

Air Force’s Operation Pot Pie Made Jupiter Missiles “Unidentifiable”

Sixty years ago, during April 1963, the US Air Force took steps to implement the final stage of the secret US-Soviet deal that helped resolve the Cuban Missile Crisis with the dismantling of the Jupiter missiles deployed in Italy and Turkey. While Air Force leaders had no knowledge of the secret agreement, they had instructions from the Defense Department and the Joint Chiefs of Staff to remove the Jupiters and to render them “unidentifiable,” according to the Air Force’s declassified “Plan for the Withdrawal and Disposition” of the Jupiter system published here today for the first time by the National Security Archive and the Wilson Center's History and Public Policy Program. The Air Force dubbed the dismantling operations Pot Pie I (Italy) and Pot Pie II (Turkey).

Getting to the point where Pot Pie could be implemented was not easy. While negotiations with Italy had been relatively straightforward, Turkey’s Chiefs of Staff were reluctant to move forward on dismantling the Jupiters. According to a declassified State Department memorandum, US officials worried that the “crisis of confidence” could lead Turkish defense officials to “stall” parliamentary approval of the operation or unnecessarily delay “technical level” understandings on Jupiter removal. Especially concerning to the State Department was that a plan then in the works to cut levels of US military aid could upend Turkish confidence. Secret talks between US and Turkish military officials in March 1963, however, improved the atmosphere with assurances of higher levels of aid. Within weeks, the US and Ankara signed off on a dismantling agreement.

As necessary as removing the Jupiters was to fulfill the secret deal, top policymakers did not want to shine a spotlight on the matter. As preparations were underway to dismantle the missiles, on March 30, 1963, the State Department reminded the US embassies in Ankara and Rome of the need to “avoid fallacious comparison between Jupiter dismantling and withdrawal [of] Soviet missiles from Cuba.” To minimize that risk, neither the US, Italy, nor Turkey should provide “official facilitation [to] press or photo coverage of missile dismantling.” To prevent too much “mystery” over the dismantling, however, the State Department advised against any Italian or Turkish efforts to block the photography of trucks carrying missiles away from military bases.

Today’s posting by the National Security Archive and the Nuclear Proliferation International History Project (NPIHP), a part of the Wilson Center's History and Public Policy Program, is the second of a two-part series on the execution of the secret deal that helped settle the Cuban Missile Crisis. The arrangement made by Attorney General Robert Kennedy and Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin stipulated that, in exchange for the Soviet withdrawal of missiles from Cuba, the US would reciprocate with a non-invasion pledge and the withdrawal of the Jupiter missiles from Turkey in “four or five months.” The Dobrynin-Kennedy conversation did not mention the Italian Jupiters, but the US had to remove them to make the Turkish deal less conspicuous. As both Part I of this posting and today’s Part II indicate, the process of removing the missiles from Italy and Turkey was not easy, automatic or effortless. Both countries had seen the missile deployments as symbols of a US security commitment, making it necessary for the Kennedy administration to persuade Italian and Turkish leaders that what they would receive in place of the Jupiters would be beneficial to their security.

Part I of the posting illuminated Italian and Turkish reactions to US proposals for removal of the Jupiters. Turkish Defense Minister İlhami Sancar was concerned about the adverse impact on his country’s “confidence” in the US, while Italian Defense Minister Giulio Andreotti worried that it represented a “graphic step backward” for Italy’s role in nuclear deterrence. Rome and Washington, however, reached a high level understanding relatively quickly, expedited by the January 1963 meeting between President Kennedy and Prime Minister Amintore Fanfani, in which the latter agreed to the “modernization” of NATO nuclear forces by substituting Polaris patrols in the Mediterranean for the Jupiters and by replacing obsolete Corporal missiles in Italy with up-to-date Sergeant missiles. While Turkey’s Foreign Minister Feridun Erkin announced in January 1963 that his government had accepted the withdrawal of the Jupiters and their replacement with the Polaris patrols, his was not the final word on the matter, and it was still necessary to convince the Turkish military.

Part II of the posting on the Jupiters covers the last phases of US action to remove the Jupiters through official agreements with Italy and Turkey, notifications to the North Atlantic Council, tricky negotiations with the Turkish military, and the dénouement: the US Air Force’s implementation of Operations Pot Pie I and II. Like Part I, this posting includes declassified documents that have not been published before, including material from the files of Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Maxwell Taylor and the records of the US Embassy in Italy. The editors intended to include several Italian archival documents but permission to do so has either been refused or not yet granted.

Among the new documents are the final agreement between the US and Italy on the Jupiter dismantling, notifications to NATO on the Jupiter/Polaris “modernization” arrangements, strategic retargeting requirements dictated by the removal of the Jupiters, and a memorandum from JCS Chairman Taylor to Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara quoting General Lauris Norstad’s opposition to the Jupiter withdrawal as “weakening our nuclear capability.” Other documents detail the plans for Polaris submarines patrols in the Mediterranean, including a submarine visit to Turkey’s port of Izmir. The latter was seen as a demonstration of the US commitment to Turkish security, especially to address concerns that the Polaris system had a “remoteness which lessens its appeal.”

An especially striking item is a translation of excerpts from a history of the Jupiters in Italy prepared by retired non-commissioned officer Antonio Mariani and published by the Historical Office of the Italian Air Force. The excerpts detail the role of the Air Force in the missile dismantling process, including the emotional reactions of personnel who had been closely involved in the Jupiter deployment: “A frenetic destructive activity pervaded the military community which, almost with anger and a certain sadism, destroyed and reduced to useless remains everything on which it had studied, worked and operated.”

Getting to an agreement with the government of Turkey was a crucial development that is documented in Part II. It was the Jupiters in Turkey that had most aggravated Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev when they were first deployed, and their removal was essential to realize the secret deal.[i] Just as was the case with Italy, the US had to find a way to carry out its end of the trade “without appearing to do so” and without antagonizing the Turkish government.[ii] As noted in Part I, the US tried to ease suspicions by characterizing the arrangements as the “modernization” of nuclear forces. While the details were different in the Italian and Turkish cases, the crucial point for both was the US proposal to substitute up-to-date and relatively invulnerable Polaris submarine launched ballistic missiles for obsolete and vulnerable Jupiter missiles. Securing Italian, Turkish, and NATO support for the modernization plan was the Kennedy administration’s key objective.

In dealing with the more demanding Turkish government, US Ambassador Raymond Hare played a central role, and his job was difficult. Unlike the Italian case, there had been no direct interaction between heads of state that could expedite the process. While Hare could reach agreement in principle with Foreign Minister Erkin, the latter acknowledged that the military had the “final word." That problem made a US military role in the talks essential. To encourage Turkey’s General Staff to accept the dismantling of the missiles, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara tasked General Robert J. Wood, the director of Defense Department military assistance programs, to negotiate with them, which he did during March 10-13, 1963.

The full story of Gen. Wood’s negotiations with the Turkish military cannot be told from the available archival records. For example, the memoranda of conversations of the talks with the Turkish General Staff are classified top secret at the US National Archives, although a declassification request by the National Security Archive may eventually lead to their release.

Gen. Wood and Turkish military officials may have discussed delays in the availability of nuclear weapons to Turkey since President Kennedy had required the installation of Permissive Action Links (PALs) to prevent unauthorized use. The declassified record also indicates that Washington disabused Ankara of the notion that Turkish officers or sailors would have a role in the operations of the Polaris submarines patrolling the Mediterranean. As previously noted, Washington would not accept this arrangement, but it did agree that a Polaris submarine would visit a Turkish harbor and that Turkish and Italian officers at SACEUR (Supreme Allied Commander Europe) headquarters would play a role in selecting targets for Polaris missiles.

Another element of the agreement with Turkey was the early delivery of F-104 nuclear capable fighter-bombers to Turkey, which, from the beginning of the negotiations, Washington saw as a “carrot” to expedite Turkish cooperation. But Turkey wanted a third squadron, and what the US promised remains unknown. One major element of the overall understanding is clear, however: As a confidence building measure, the White House decided to reverse scheduled cuts in the Military Assistance Program (MAP) and provide the Turkish armed forces with higher levels of aid.

In Ambassador Hare’s words, the Wood mission provided “reassurance” to the Turkish military, thereby playing a “large role in obtaining [their] cooperation” in the details of the “missile substitution.” Wood also accepted a Turkish proposal of a Polaris submarine visit the port of Izmir. The US Navy objected to Izmir for technical reasons, but the State Department and General Wood believed that it was suitable enough and successfully pressed Defense Department higher-ups to accept it.

In the weeks after General Wood’s talks, the Jupiter dismantling operation began to fall into place. In late March, the US and Italy exchanged notes on the Jupiter-Polaris arrangement, while John McNaughton reported to McGeorge Bundy that the dismantling in Italy would begin on April 1 and in Turkey on April 15. Early that month, the US and Turkey exchanged notes, although the agreement remains classified. During early April, the dismantling of Jupiter missiles in Italy began. On April 15, dismantling began in Turkey. The day before, as part of the arrangements, the Polaris submarine USS Sam Houston stopped at Izmir for a multi-day visit that provided positive media coverage. On April 25, 1963, Secretary of Defense McNamara sent a brief note to President Kennedy that the last Jupiter in Turkey “came down yesterday.”

For the US Defense Department, General Counsel John McNaughton played a directing role in the implementation of the Jupiter removals. According to McNaughton’s oral history with the Kennedy Library, in early 1963, he was given overall responsibility for removal of the Jupiters and their replacement with Polaris patrols. In the interview, he asserted that the Jupiter/Polaris operation had nothing to do with the missile crisis settlement. Robert McNamara, who gave McNaughton his assignment, did nothing to enlighten him on that point. He later recalled that he instructed McNaughton not to ask why he was getting the assignment because “I’m not going to tell you.” Unfortunately, McNaughton’s records as general counsel are not available, and his name appears in few of the declassified records, although notably in document 25.[iii]

The importance of the secret deal makes it worthwhile to understand how it was implemented, but it also had a broader significance that is worth noting. As historian Philip Nash has argued, by removing Soviet missiles from Cuba and Jupiter missiles from Italy and Turkey, the Cuban missile swap deserves recognition as a trailblazing arms control agreement, the “first arms reduction agreement” of the Cold War. Nash contends that even though it was “verbal, informal, secret, spontaneous,” and part of a larger tacit arrangement, the secret deal was the “first agreement in the history of the arms race under which both sides dismantled a portion of their operational nuclear delivery systems.”[iv] It would take nearly ten more years before Washington and Moscow would agree to the new dismantling decisions that were incorporated in the SALT I agreement in 1972.

By then, the secrecy surrounding the deal over the Jupiters was beginning to erode. In 1970, former Turkish president and prime minister İsmet İnönü made an extraordinary statement to the Grand National Assembly, saying that, during 1963 “we … learned that [the US] had made a deal with the USSR.” Exactly how Turkish officials learned this remains obscure. Robert F. Kennedy’s memoir of the crisis, Thirteen Days, did not acknowledge an explicit agreement but recounted how he had told Soviet Ambassador Anatoli Dobrynin that the president wanted to remove the Jupiters, and that, “within a short time after this crisis was over, those missiles would be gone.” Even though Kennedy had denied to Dobrynin that there was a quid pro quo, Harvard University government professor Graham Allison surmised, in 1971, that “it could not have been plainer” that there had been one.[v]

During the 1970s, enough material had been declassified at the Kennedy Library, including detailed summaries of the ExCom discussions and State Department documents, for Stanford University historian Barton J. Bernstein to conclude that Robert F. Kennedy “privately offered a hedged promise … to withdraw the Jupiter missiles from Turkey at a future time.” More information became available during the 1980s, but it was not until 1989 that John F. Kennedy’s speechwriter/counsel, Theodore Sorensen, made his “confession” that he had altered Robert Kennedy’s memoir to conceal the fact that removing the Jupiters had been part of the agreement with the Soviets. The release from Russian archives of Ambassador Dobrynin’s telegraphic report of his meeting with Robert F. Kennedy provided essential confirmation of the secret quid pro quo.[vi]

Background Documents

Talking Paper for the Chairman, JCS, for Discussion with the Deputy Secretary of Defense on 26 December [1962]: 'Planning Requirements Resulting from the Nassau Pact and the JUPITER Decision'

JCS Chairman Maxwell Taylor was aware of Kennedy’s Jupiter decision, but it is not clear when the other Chiefs learned of the “closely held decisions.” This paper, approved by General Paul S. Emrick, director of Plans and Policy for the Joint Staff, gave an overall look at the “planning requirements” necessitated by the Jupiter decision and the recent Nassau conference between President Kennedy and UK Prime Minister Harold Macmillan. Among the issues presented by the withdrawal of the Jupiter missiles were retargeting requirements, Sergeant missiles for Italy, the number of Polaris submarines patrolling the Mediterranean and their basing, and the speeding up of F-104G deliveries to Turkey.

JCS Telegram 7947 to USCINCEUR [Commander-in-Chief European Command], CINCLANT [Commander-in-Chief Atlantic Command] and DSTP [Director Strategic Target Planning Staff], Offutt Air Force Base, Info for CINCSAC [Commander in Chief Strategic Air Command]

This urgent message “of the highest sensitivity” from the Joint Chiefs to top commanders began with a misrepresentation of President Kennedy’s decision: “serious consideration [is] being given to withdrawal of JUPITERS from Italy and Turkey.” The recipients—General Lyman Lemnitzer [CINCEUR], Admiral Robert Dennison [CINCLANT], and General Thomas Power [DSTP]—were to assume that Italy and Turkey had agreed to the decision, that withdrawal of the Jupiters would occur by April 1, 1963, and that Polaris submarines would be in the Mediterranean by that date. Both USCINCEUR and DSTP, who directed work on the SIOP, were to consider retargeting requirements once the Jupiters went offline. CINCLANT was to consider the feasibility of deploying one, two, or three submarines.

Memorandum from Maxwell D. Taylor for the Secretary of Defense [Robert McNamara], 'Withdrawal of Italian and Turkish JUPITERs'

Taylor forwarded to McNamara the views of USCINCEUR, CINCLANT, and the DSTP on targeting and submarine deployment issues. According to CINCLANT Admiral Dennison, it was feasible to deploy up to three Polaris submarines in the Mediterranean. They could regain the same “operating efficiency” that they had achieved in their previous Norwegian Sea deployment. In Lemnitzer’s absence, General Lauris Norstad, who was departing as CINCEUR, opposed the withdrawal of the Jupiters as “weakening our nuclear capability” by reducing target coverage and by “destroying” the Jupiter’s “psychological” impact. DSTP General Power was also concerned about target coverage but did not foresee “basic problems as long as Free World missiles are targeted as an integrated package.”

JCS Telegram 8283 to USCINCEUR and CINCLANT, 18 January 1963, Top Secret

This message conveyed several decisions that McNamara had detailed in a memorandum on “The Replacement of Jupiter and Related Matters.” One Sergeant missile battalion would be deployed in Italy to replace Corporal missiles. The U.S. would not transfer to Italy “operational responsibilities” for nuclear weapons currently deployed to the Southern European Task Force [SETAF]. The U.S. would not deploy Pershing missiles to Italy. Planning would begin for the assignment of three Polaris submarines to the Mediterranean beginning April 1, 1963. Finally, plans would be made to deliver 14 104-G’s to Turkey during April 1963.

Memorandum for the Record by Lt. Colonel R. B. Spilman, Assistant Secretary, 'Summary of Discussions by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Deputy Director, STPS [Strategic Target Planning Staff], Regarding Retargeting to Cover Withdrawal of JUPITER Missiles from Turkey and Italy'

The Joint Chiefs met with Admiral Roy L. Johnson, the deputy director of the Joint Strategic Targeting Planning Staff [JSTPS], to discuss how to cover the target gap left by the dismantling of 45 Jupiter missiles and also the gap that would be caused by the temporary absence of one Polaris submarine during its transit from Holy Loch (Scotland) to the Mediterranean. Johnson saw the missile shortage as one that would be of “decreasing significance after July 1963” when more ICBMs would be entering the nuclear arsenal. To complete retargeting of the previous Jupiter targets would take 90 days while retargeting of the Polaris submarines, which involved “cutting new cards for the computers,” would take several months. Johnson reviewed in detail the problems involved in providing coverage of the previously targeted bomber bases, military control centers, and other targets.

JCS Chairman Taylor emphasized the importance of assuring General Lemnitzer that retargeting would not injure NATO’s position and that the U.S. would retain the “present level of missile attacks” against Soviet missile and bomber bases that threatened NATO. Johnson made suggestions for “alternative criteria” to provide coverage of Soviet threat targets, while the Chiefs conveyed their criteria for retargeting, such as the same level of damage expectancy for the Jupiter targets.

Written on top of this document is the word “SIOP [Single Integrated Operational Plan]” because the targeting problems that the Chiefs were discussing with Admiral Johnson were integral to the U.S. nuclear war plan.

“Carrots” for Turkey While Avoiding “Undue Pressure”

OSD [Office of Secretary of Defense] Telegram 020123Z to Department of State, 1 February 1963, Secret

By late January, the negotiations with Turkey were bogged down, with Defense Minister Sancar asking for a Turkish military presence on the Polaris submarines as well as delivery of nuclear weapons for the F-100 Super Sabres before the Jupiters were replaced. Without a formal agreement on the Jupiters, the U.S. government held back from a decision on another matter: the delivery of F-104G fighter-bombers. Nevertheless, Defense Department officials approved a decision to “provide first available aircraft” in April 1963, which was necessary to authorize the Air Force’s “preliminary preparatory actions.” The U.S. would preserve its “bargaining position” by informing Turkey in writing that an “accelerated delivery date will become firm upon satisfactory conclusion of current US/Turkey negotiations.”

Department of State Telegram 680 to the American Embassy Ankara

The State Department remained concerned about reaching an agreement with Turkey in “principle without unfulfillable conditions of replacement Jupiter.” To move the negotiations along, this communication authorized Ambassador Hare to use as a “carrot” the Defense Department’s conditional approval of F-104 deliveries. It also advised him to avoid any “undue pressure” that could harm the negotiations.

Department of State Telegram 1490 to the American Embassy Rome

In this overview of the state of the Jupiter/Polaris negotiations and the next steps, the State Department instructs Ambassador Hare to lead the negotiations with Turkey and to inform U.S missions that McNamara’s letter to Andreotti on the Polaris and Sergeant deployments was in the works; that Turkish “conditions” were not clear; that the U.S. and the two countries had to formally notify NATO of the “modernization” program; that bilateral agreements with Ankara and Rome on the Jupiter/Polaris arrangement would need to be negotiated; that steps had to be taken to prepare Polaris submarines for missions in the Mediterranean by April 1; and that the U.S. needed “considerable lead time” to prepare for the removal of the Jupiters. The negotiation of Turkey’s conditions for the Jupiter removal should not hold up notifying NATO or cause delay of the U.S.-Italy arrangements. On the use of the naval base at Rota, Spain, for stationing Polaris submarines, several NATO governments had objected (because of the Franco dictatorship), and so far Madrid had rejected U.S. proposals.

American Embassy Ankara Telegram 911 to the Secretary of State, Washington, DC

In this telegram, Hare asks Foreign Minister Erkin where things stand and informs him that the U.S. would be ready to “take speedy implementation action” on the Jupiters once Turkey had decided. Alluding to the military’s pivotal role in important government decisions, Erkin says that the military has the “final word,” and he would let Hare know once he has heard from them.

JCS Message 8569 to USCINCEUR, 8 February 1963, Secret

The Joint Chiefs sent General Lemnitzer this outline of the current plans to remove the Jupiter missiles. The main points are that the Jupiters should be inactivated by April 1 (although that was more likely for Italy than for Turkey), that one Polaris submarine should be in the Mediterranean by March 28 and a second one by April 10, that the JCS are taking steps to retarget weapons for when the Jupiters are offline, and that guidance on the Italian and Turkish role in the targeting of Polaris missiles has been prepared.

Memorandum for the Secretary of Defense from Major General John M. Reynolds, Vice Director Joint Staff, 'Withdrawal of Jupiter Missiles,' 9 February 1963, Top Secret, Excised Copy

The Joint Staff prepared a detailed and lengthy report in response to a request from the Defense Department’s Office of International Security Affairs for an “outline plan for withdrawal and complete disposition” of the Jupiter missiles. A number of options were considered and rejected, including other military uses, offering the Jupiters to other agencies as a space booster, storing the missiles, and destroying them “without reclamation.” As there was “no identifiable requirement for the missiles,” the most appropriate option was “promptly dismantling and removing [them] from operational launch site.” While the warheads should be speedily returned to the United States, other useful components could be reclaimed, and the rest could be salvaged. The process would prevent the loss of high value components that were still usable, such as rocket motors, fueling trailers, and electronic devices. Such an outcome required decisions on the final disposition of Jupiter assets.

Department of Defense Briefing Book, Mr. Gilpatric’s Visit to Rome 11-12 February 1963

Deputy Secretary of Defense Roswell Gilpatric visited Rome in February 1963 for meetings with Prime Minister Fanfani and Defense Minister Andreotti. The Jupiter missiles were on the agenda and this lengthy briefing book conveys the tacit linkage between the Jupiter dismantling and the range of nuclear and conventional forces issues that were then under discussion. They included, among others: the possible deployment of Polaris aboard the cruiser Garibaldi, “with the US retaining custody of the warheads”; the long-standing Italian quest for help in the development of a nuclear-powered submarine; and the conclusion of an arrangement for a co-production of M-113 armored personnel carriers in Italy.

Perhaps the most striking part of this compilation is the paper reviewing the Italian experiment to use the cruiser Garibaldi as a delivery vehicle for Polaris missiles. According to the briefing paper, the main U.S. objection to the Garibaldi proposal had less to do with its technical aspects than with the broader NATO context. The problem with a bilateral deal was political, namely the Garibaldi’s potentially negative impact for the creation of a multilateral NATO force, including the potentially adverse repercussions for Turkey and West Germany.” The former could see it as an “unfair advantage to Italy ... in the matter of [the] adequacy of a replacement for Jupiter missiles,” while the latter could see it giving Italy “some of preferred status.”

Not included in the copy that went to the State Department are the probably more sensitive papers on Polaris forces and the “Assignment of Forces” to NATO.

American Embassy Rome Telegram 1612 to the Secretary of State, Washington, DC

Detailed records of the conversations between Gilpatric and top Italian officials have yet to surface. The sole source is a telegram from the Rome Embassy summing up the talks with Fanfani. On February 11, Gilpatric and Ambassador G. Frederick Reinhardt met with Prime Minister Fanfani. Gilpatric reviewed U.S. plans for three Polaris submarines assigned to SACEUR to patrol the Mediterranean and the projected visit to Rome by Ambassador Livingston Merchant to discuss the multilateral force proposal. In that connection, Fanfani said that Italy had given up the proposal to equip the Garibaldi with Polaris missiles. Gilpatric discussed some of the negative implications of French President Charles De Gaulle’s 14 January 1963 press conference, which included statements critical of NATO. This raised concerns in Washington that if the American people felt “unwanted” in Europe, there might be pressure to take a “more restrictive” position on the U.S. military presence in Europe. Fanfani agreed that it was “more important than ever for … the alliance to strive for greater unity.”

Department of State Telegram 1150 to the American Embassy Paris

To bring NATO officially on board, the State Department sent this draft paper to U.S. ambassadors in Italy, NATO, and Turkey for use with the North Atlantic Council and with SACEUR. Just as the three governments had informed the Council of the Jupiter deployment plans in the late 1950s, they would brief the NAC on the purposes of the Jupiter-Polaris arrangement and its military implications, including retargeting requirements for the “timely damage” of Allied Command Europe targets.

American Embassy Paris Telegram NIACT POLTO 77 to Rome

Responding to the State Department proposal for a memorandum to NATO on the Jupiter/Polaris arrangements, Ambassador Thomas Finletter writes that Italian officials suggested that government approval would be expedited if the draft were “altered to become a United States memorandum” in which the Italian and Turkish representatives “simply concur.” When Finletter suggested that the proposal was not workable, the Italians responded that their government would “accept present text.” NATO Secretary General Dirk Stikker did not see any serious problem, even if the substitution of Polaris for Jupiters caused “some reduction in target coverage.” Stikker asked that the U.S. “squash [the] rumor” that Polaris would be based at Rota, Spain (which was in fact the U.S. objective).

It is not clear exactly when the North Atlantic Council received this memorandum, but it may have been on February 22, 1963, the preferred date, from the State Department’s perspective, for avoiding delays in the removal of the Jupiters.

American Embassy Ankara Telegram 970 to the Secretary of State, Washington, DC

A number of issues raised by Defense Minister Sancar about the Jupiter agreement were unresolved. While some in the Turkish government wanted to withdraw Sancar’s letter to McNamara, President İnönü was reluctant to do that, wanting it understood that what Sancar had written “were not conditions but rather expression of Turkish needs and desires.” During a meeting, Foreign Minister Erkin told Hare that he was trying to clear the proposed memorandum to the NAC in time for its meeting on February 20. On the sentence about Polaris submarines operating in the Mediterranean, Erkin suggested this wording: Polaris was being “especially assigned” to Italy and Turkey. That would speak to the “Turkish feeling” that “Polaris has remoteness which lessens its appeal.”

Later that day, Hare wrote that the Turkish government was apparently willing to sign on to the statement to NATO. That Turkey had already made the “political decision” to dismantle the Jupiters made it necessary for the U.S. to address Sancar’s concerns, such as the nuclear weapons for the F-100s, the delivery of a third F-104 squadron, access to the facilities at Cigli, and Turkey’s role in the Polaris submarines. Hare also favored a positive response to Sancar’s proposal for negotiations between U.S. and Turkish representatives.

Memorandum from JCS Chairman Maxwell Taylor to the Secretary of Defense, 'Deployment of POLARIS Submarines to the Mediterranean' 21 February 1963, Top Secret

Consistent with the concerns about target coverage, the plan for Polaris patrols required the presence of at least one submarine in the Mediterranean. The overlapping patrols would begin when the U.S.S. Sam Houston entered the Mediterranean on March 28, followed by the U.S.S. John Marshall on April 10, and the U.S.S. Ethan Allen on 1 June. The Sam Houston could make a port call in Turkey, but the stopover had to occur when another submarine was in the Mediterranean. Taylor recommended the port of Glock as the site of a two-day visit, one day for a visit by officials and the second for a “daylight indoctrination cruise by designated observers.” The latter would be barred from sensitive “spaces” used for communications and nuclear propulsion.

Trying to Nail Down Final Agreements and Obstacles Encountered

Department of State Telegram 1659 to the American Embassy Rome

The State Department sent the embassies in Ankara and Rome the text of a draft note to be used in negotiations with both countries for formal agreements on the removal of the Jupiter missiles and their replacement with Polaris submarines operating in the Mediterranean. The dismantlement of Jupiter sites in Italy would “begin concurrently with the arrival of the Polaris submarines in the Mediterranean” around April 1, while the dismantling in Turkey would begin with the arrival of the second Polaris submarine on or about April 15.

American Embassy Ankara Telegram 1030 to the Secretary of State, Washington, DC

Hare delivered McNamara’s response to Sancar’s letter to Erkin, who found it “very good, very constructive.” While reading it, Erkin observed that Sancar had been difficult, not for “reasons peculiar to him” but because there was a “general uneasiness” that “things may be happening which affect Turkey, but to which GOT is not privy.” That perception had an impact on Sancar’s “desire … for physical [Turkish] presence on Polaris.”

Department of State Telegram 800 to the American Embassy Ankara

The U.S. had hoped that an exchange of notes with Turkey on the Jupiter/Polaris arrangement would facilitate a technical level approach to the Turkish military on the “mechanics of Jupiter dismantling.” But with parliamentary approval of the notes delayed, and not likely to occur until later in the month, the U.S. needed to make an approach on dismantling so that it occurred in conjunction with the arrival of Polaris submarines in the Mediterranean. With dismantling scheduled to begin on April 15, the Department would like Hare’s advice on whether a technical approach could be made “without running unacceptable political risk.”

General Wood’s Mission

Department of State Telegram 808 to the American Embassy Ankara

Following up on earlier ideas about direct talks with Turkish officials, General Robert Wood, the director of Military Assistance Programs at the Department of Defense, would be visiting Turkey for talks. This State Department message notes that in light of proposed overall cuts of foreign aid, projected military aid to Turkey would total $120 million, and U.S. officials would emphasize Washington’s “continuing long term interest” in Turkey’s military capabilities. Issues for Hare’s consideration include the “adequacy” of the proposed approach and what needed to be done to bolster Turkish “confidence and morale” and to prevent any “stalling” on the Jupiters.

American Embassy Ankara Telegram 1060 to the Secretary of State, Washington, DC

The Embassy reports to the State Department that the ratification of an exchange of notes by the Grand National Assembly would not prevent the U.S. from early initiation of a “technical level” approach on dismantling the Jupiters. No “unacceptable political risks” would be involved. Turkey’s participation in the presentation to the NAC meant that “we can probably take it for granted we have final answer and proceed accordingly up to point of physical removal.”

Memorandum from NEA [Assistant Secretary for Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs] Philips Talbot to G [Deputy Under State of State for Political Affairs Alexis] Johnson, 'FY 1964 MAP Levels as Basis General Wood’s Discussions in Turkey'

According to Talbot, an impasse in the impending talks between General Wood and the Turkish General Staff could have damaging implications for the removal of the Jupiters and for U.S.-Turkish relations. A key issue is the level of Military Assistance Program spending for the modernization of the Turkish Armed Forces, with the Turks believing that they “need and deserve” a higher modernization rate than the U.S. had programmed. For the Turkish military, $120 million would represent a “sudden and catastrophic decline.” Citing the importance of keeping the military “in line,” Talbot cites Ambassador Hare’s argument that “it would be difficult to conceive a worse time for making a significant reduction in MAP” and urges Johnson to authorize Gen. Wood to start with a “base of least” $150 million.

American Embassy Ankara Telegram 1063 to the Secretary of State, Washington, DC

Concerning levels of military aid, Hare warns that “abrupt and negative action on our part could have certainly foreseeable reaction detrimental not only to proper resolution of existing problems but also to our fundamental relationship” with Turkey.

Department of State Telegram 820 to the American Embassy Ankara

The Kennedy administration found it necessary to solve the problem raised by Ambassador Hare lest military assistance cuts delay or prevent action to dismantle the Turkish Jupiters. After the Wood mission left Washington, in accordance with NSC 1550 (setting requirements for foreign aid funding decisions), the State Department undid the cuts by authorizing Wood to discuss specific quantities of approved equipment that could be delivered during FY 1963 and quantities and types of equipment that could be provided during FY 1964. For the latter, equipment could be provided up to a level of $150 million (thus providing the modernization resources sought by the Turkish military), but Wood was not to mention any dollar values during the talks.

John W. Bowling, GTI [Bureau of Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs, Office of Greek, Turkish, and Iranian Affairs] to Mr. Kitchen, G/PM [Office of Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Political-Military Affairs], 'General Wood’s Visit to Turkey'

Having accompanied General Wood on the mission to Turkey, Bowling provides Kitchen with a copy of the top secret record of the discussions with the Turkish General Staff (which remain classified). According to Bowling, Wood “accomplished his mission” by conducting the talks with “great skill and vigor”: “There will be no stalling on Jupiter removal from the Turkish military.” With the Turkish Chiefs of Staff “badly shaken up” by the implications of the Jupiter removal, Wood helped check “the slide in … morale” by addressing concerns about MAP funds, Turkish participation in Polaris targeting, the selection of a port for the Polaris visit (with Izmir preferred by Turkey), and the disposition of facilities at Cigli.

Department of State Telegram 1772 to the American Embassy Rome

The State Department instructs the Embassy to inform Italian authorities that if the Jupiter dismantling was to be completed within the first 25 days of April, as the Italian government requested, military officials needed to be notified accordingly. According to the Deputy CINCEUR, Italian military officials had not yet received authorization on the dismantling. The State Department hoped that Italian military personnel would be available for the operation “notwithstanding Easter holidays."

American Embassy Ankara Telegram 1097 to the Secretary of State, Washington, DC

Hare informs the Department that, in light of the Wood mission, the Turkish military would not request any changes in the text of the notes to be exchanged on the Jupiters/Polaris arrangement. It might be possible for the Turkish government to sign an “executive-type” agreement instead of taking the matter to parliament. With the U.S. willing to talk with Turkish officials and provide “reassurance,” the Wood mission “played large role in obtaining Turkish cooperation” in the details of the “missile substitution.”

Moving Forward on Dismantling and Finalizing Agreement with Italy

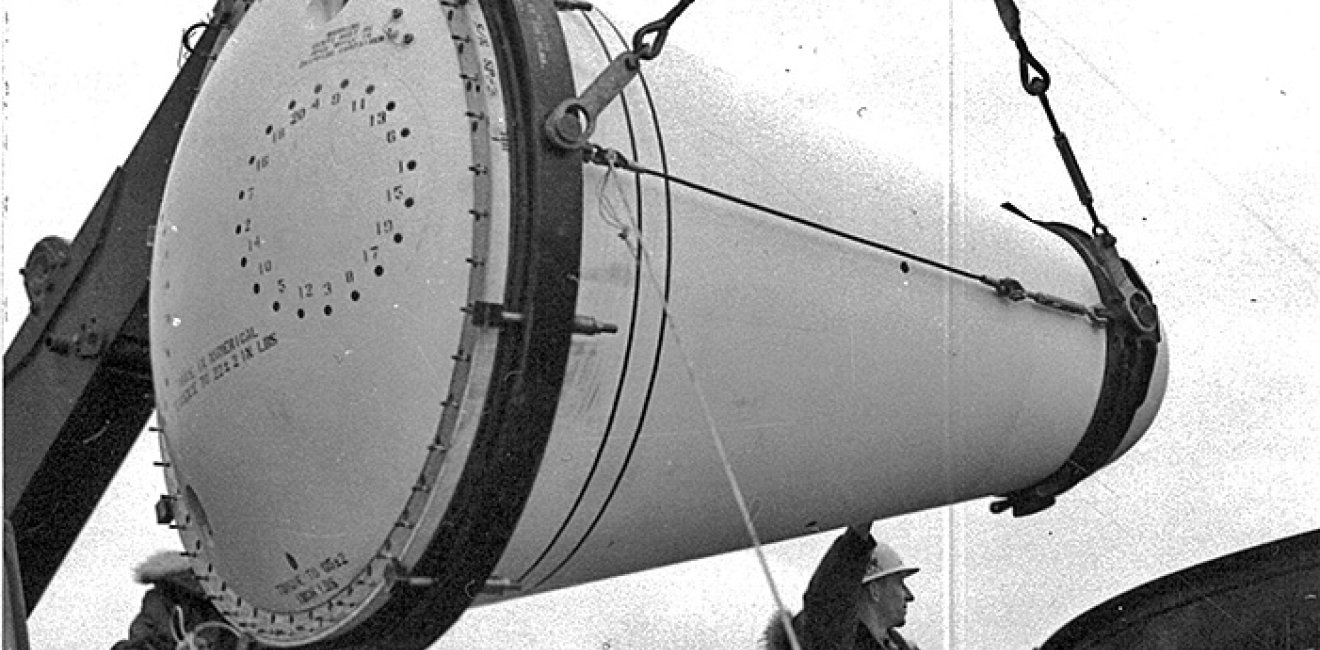

Memorandum from Major General W. O. Senter, Assistant Deputy Chief of Staff, Systems and Logistics, U.S. Air Force, with attachment 'A Plan for the Withdrawal and Disposition of the SM-78 (Jupiter) Weapon System from Italy and Turkey [:] Operation Pot Pie'

The Joint Chiefs of Staff had appointed the Air Force as “Executive Agent” for taking charge of the Jupiter removal from Italy and Turkey, and Air Force General William Senter signed off on the plan of action. Under the plan, the Jupiter’s classified components, including the warheads and guidance systems, would be returned to the United States, while remaining portions of the missiles were to be rendered “unidentifiable,” the meaning of which was described in detail (PDF p. 7): removal of the missiles from launching areas, separating the engines from the missiles, dismantling “sub-systems,” and “orderly disposition of the remaining components.” This was consistent with the Joint Staff’s recommendations for salvage procedures to ensure that both Italy and Turkey had access to useful non-sensitive equipment and parts. Under the plan, various U.S. military organizations, including the Italian and Turkish Air Forces, would have specific responsibilities, which were described in detail as were procedures for the return of the warheads, re-entry vehicles and guidance systems to the United States.

The dismantling operation in Italy, nicknamed Pot Pie I, would begin on April 1, while the operation in Turkey, Pot Pie II, would begin on April 15, with a “minimum of publicity” in both countries. The plan would be classified as “Confidential NOFORN,” although, as noted, elements of it were to be shared with Italian and Turkish officials.

American Embassy Rome Telegram 1890 to the Secretary of State, Washington, DC

The Embassy had informed the Italian Foreign Office of the need to coordinate the dismantling with military officials, but, according to the U.S. military assistance mission, Ministry of Defense officials were without instructions. An “early exchange of notes would help button up matter promptly.” The Embassy made the point that the “action to be completed within 25 days includes removal from Italy of nose cones, warheads and guidance systems, and laying missiles in horizontal positions, but that salvage of missile hulls and disposal of assorted administrative equipment … might take as long as six-eight months.”

American Embassy Rome Airgram A-1368 to State Department, 'Exchange of Notes Affecting Replacement of Jupiter Missiles in Italy'

On March 22, 1963, through an exchange of notes, the U.S. and Italy confirmed the final agreement on the dismantling of the Jupiter missiles and their replacement with patrols of Polaris submarines assigned to the Supreme Allied Commander Europe. The Polaris patrols would begin on April 1, 1963, and the dismantling operation would occur during the next 25 days.

Memorandum from John McNaughton, General Counsel, Department of Defense, to McGeorge Bundy

One of the few pieces of declassified evidence showing John McNaughton’s role in the Jupiter removal process, his report to McGeorge Bundy concerned the “physical operation” to remove the missiles and the related press management. Dismantlement actions would begin on April 1 in Italy and April 15 in Turkey. For both countries, the dismantled missiles would go to a “graveyard.” The arrival of Polaris submarines during April would be publicized along with a visit to Turkey around April 14-15. No photographers would be allowed on site, but no “special limitations” would apply when the missiles were in transit. One of McNaughton’s concerns was that the dismantling operation be handled in a way that “reduced[d] … erroneous comparisons with Cuba.”

Department of State Telegram 1905 to the American Embassy Rome

The State Department instructs the embassies in Ankara and Rome of the importance of avoiding “fallacious comparison between Jupiter dismantling and withdrawal Soviet missiles from Cuba.” To help do that, the embassies should ensure that “no official facilitation will be given press or photo coverage of missile dismantling.” In response to any press queries, the embassies could state that “dismantled missiles will be transported over period several weeks.” To avoid an “air of mystery” around the dismantling, the Department opposed efforts to block media coverage of missiles in transit. The embassies should approach Italian and Turkish officials “along [those] lines.”

The Last Steps and the Polaris Submarine Stop at Izmir

American Embassy Paris Telegram 4035 to the Secretary of State, Washington, DC

Walter Stoessel, Political Adviser to SACEUR General Lemnitzer, informs the State Department that Secretary of Defense McNamara has written to Turkish Minister of Defense Sancar that a Polaris submarine “on duty” in the Mediterranean would visit the port of Izmir, in compliance with Sancar’s recommendation. Sancar was also informed that, during the Polaris visit on April 14-15, “selected guests will be accommodated.”

American Embassy Ankara Telegram 1208 to the Secretary of State, Washington, DC

The Embassy informs the Department of last-minute developments concerning the exchange of notes on the Jupiter/Polaris arrangement. Hare confirmed with Foreign Minister Erkin that the dismantling would begin on April 15, and that was “reconfirmed … at working level.”

American Embassy Paris Telegram 4136 to the Secretary of State, Washington, DC

A SHAPE news release would announce the “courtesy call” by the Polaris submarine, U.S.S. Sam Houston, to Iszmir, Turkey, beginning on April 14. The visit will “provide an opportunity for distinguished Turkish officials to view this latest weapon system to be assigned to the defense of Allied Command Europe.”

American Embassy Ankara Telegram 1234 to the Secretary of State, Washington, DC

The U.S. Embassy in Ankara informs the State Department that the exchange of notes has been completed. The agreement text has yet to be declassified.

American Embassy Ankara Telegram 1270 to the Secretary of State, Washington, DC

Reporting on the visit of the Polaris submarine U.S.S. Sam Houston to Izmir, the Embassy finds it to be a “success from all points of view.” The press provided “maximum favorable coverage,” with one headline stating that the “Submarine which scares Soviets is in Izmir.” The press coverage emphasized the “power of atomic sub weapons as deterrent,” the “warmth of welcome extended to ship,” and the “importance of the dignitaries” who visited the ship.

This document is possibly an incomplete cross reference copy, and the original version was not found.

Note from Secretary of Defense McNamara to President Kennedy

In a hand-written note, McNamara reports that the last Jupiter missile in Turkey “came down yesterday” and that “The last Jupiter warhead will be flown out of Turkey on Saturday.”

Antonio Mariani, La 36ª aerobrigata interdizione strategica. Il contributo italiano alla guerra fredda [The 36th Strategic Interdiction Brigade: An Italian Contribution to the Cold War]

These excerpts from the memoirs of a former member of Italy’s 36th Air Brigade, published by the Italian Air Force, provides fascinating perspective on the shock felt by officers when they received the dismantling instructions and then how they planned and carried out their tasks. The following sentences convey the emotional reactions: “The dismantling, for those who experienced it, was a real demolition. A frenetic destructive activity pervaded the military community which, almost with anger and a certain sadism, destroyed and reduced to useless remains everything on which it had studied, worked and operated.” As the excerpts makes clear, not everything was destroyed and junked. Consistent with the Joint Staff’s original proposals, sensitive components, such as the warheads were returned to the U.S., while other parts of the missiles were salvaged and made available to other organizations. Some equipment went to Italy’s “San Marco” space research program, just as Prime Minister Fanfani had proposed to President Kennedy during their meeting in January 1963.

To what extent the dismantling procedure in Turkey paralleled the one in Italy remains unclear, at least on the basis of available documentation.

Notes

[i]. For studies of the Jupiters in Turkey, see Nur Bilge Criss, “Strategic Nuclear Missiles in Turkey: The Jupiter Affair, 1959–1963,” Journal of Strategic Studies 20 (1997): 97-122; Philip Nash, The Other Missiles of October: Eisenhower, Kennedy, and the Jupiters 1957-1963 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), and Süleyman Seydi, “Turkish–American Relations and the Cuban Missile Crisis, 1957–63,” Middle Eastern Studies 46 (2010): 433-455.

[ii]. Barton J. Bernstein, “The Cuban Missile Crisis: Trading the Jupiters in Turkey?”, Political Science Quarterly 95 (1980): 107.

[iii]. Nash, The Other Missiles of October, 152. In the Kennedy Library interview, McNaughton alluded to a diary, but whether any diary material for 1963 survived is unknown. For the McNaughton diaries during the Vietnam War escalation, see Benjamin T. Harrison and Christopher L. Mosher, “The Secret Diary of McNamara's Dove: The Long-Lost Story of John T. McNaughton's Opposition to the Vietnam War,” Diplomatic History 35 (2011): 505-534.

[iv]. Nash, The Other Missiles of October, 149.

[v]. Don Munton, “Hits and Myths: The Essence, the Puzzles, and the Missile Crisis,” International Relations 26 (2012): 312-315. For İnönü’s statement see Süleyman Seydi, “Turkish–American Relations and the Cuban Missile Crisis, 1957–63,” at 451.

[vi]. Bernstein, “The Cuban Missile Crisis: Trading the Jupiters in Turkey?”, 97–125.