A blog of the Latin America Program

Left Off the Bread Line

COVID-19 has bludgeoned Latin America. Though the region is home to only 8 percent of the world’s population, it accounts for almost half of COVID-19 deaths. The virus is ravaging countries that adopted aggressive public health responses, and also those with notoriously lackadaisical policies.

President Alberto Fernández of Argentina and President Martín Vizcarra of Peru imposed some of the world’s strictest lockdowns, while President Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil and President Andrés Manuel López Obrador of Mexico maintained a recklessly laissez-faire approach. Predictably, the outbreaks in Brazil and Mexico are out of control. But despite their best efforts, the strict social distancing in Argentina, Peru and elsewhere has failed to stem a rapid growth in cases. (On August 26, Argentina registered 10,550 new cases, a record increase, and Peru now has the world’s highest rate of COVID-19 deaths.) Stay-at-home measures, meanwhile, have not come without a cost. “The lockdowns in Latin America were effective enough to kill the economy, but not effective enough to stop the virus,” the chief Latin America economist at Oxford Economics, Marcos Casarin, said.

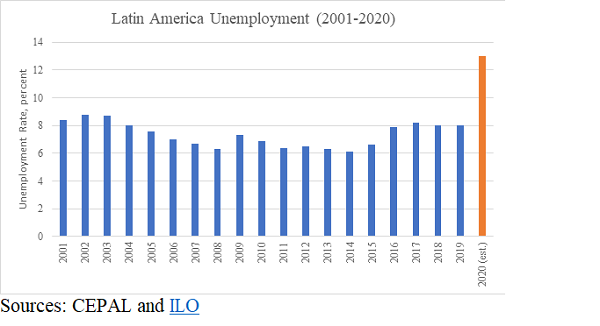

The cumulative economic impact of COVID-19 on the region is unclear, but forecasts predict the worst economic contraction in history. As a result, Latin America will see unemployment increase from 26 million in 2019 to 41 million this year. Even that does not fully capture the crisis, as millions of workers have given up the job search and no longer count as unemployed.

A better measure is the total number of jobs lost. The latest data from the Inter-American Development Bank shows over 26 million people have lost their jobs, 3.1 million in the formal sector. That figure likely underestimates the total job losses, as many countries have yet to provide their latest employment figures. Even before the pandemic, Latin America was experiencing slow growth and a worsening employment picture. This crisis will likely push the region into a prolonged period of high unemployment and poverty, with serious social consequences.

Daily Bread

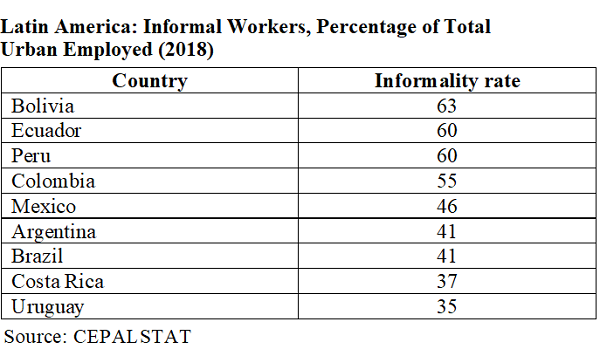

Almost 90 percent of the jobs lost during the pandemic were in the informal sector. This presents policymakers with a particular challenge. Since many countries in the region struggle to administer enough COVID-19 tests and implement contact tracing, they rely upon lockdowns as a blunt instrument to stem the spread of the virus. But lockdowns disproportionately affect the poorest, many of whom work in informal jobs – such as street merchants, construction workers or domestic employees – and have no telecommuting option.

Unlike in advanced economies, Latin America has a persistently high level of labor informality. Even in its relatively wealthy countries, formal jobs are scarce. As a result, millions of workers toil outside the social safety net, losing out on benefits such as unemployment insurance. Worse still, many of these workers have little savings to survive a lengthy interruption in earnings. As a result, dire forecasts show poverty and hunger surging in the region, despite an historic increase in government spending to address the social and economic costs of the crisis.

Budget Buster

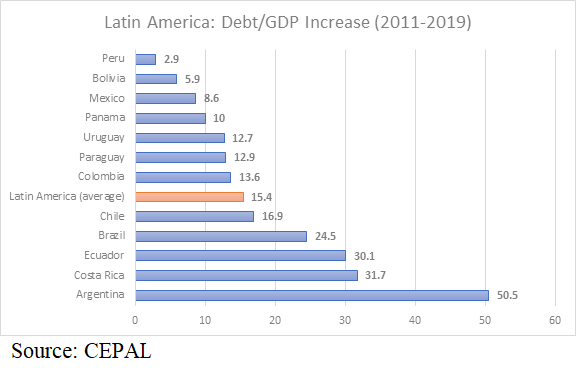

Many governments in the region have implemented large fiscal stimulus measures to mitigate the impact of the pandemic and lockdowns. So far, COVID-19-related spending accounts for 3.2 percent of the region’s GDP. Countries with records of responsible budget management, like Chile and Peru, have accessed cheap credit to cover the emergency spending (5.7 percent of GDP and 4.8 percent of GDP, respectively). Others with a history of spendthrift populism are financing their stimulus programs almost entirely by printing money, such as Argentina, where the cost of stimulus has reached 4 percent of GDP.

In either case, this massive expansion of spending comes at a bad time. Prior to the crisis, governments in Latin America were experiencing serious fiscal challenges. Revenues stagnated after 2014, as commodity prices, including energy, slid. But governments did not press the brake pedal on spending. A combination of slower growth, dampening international trade and spending inertia saw the region’s average fiscal deficit grow from 1.7 percent of GDP in 2011 to 3.1 percent of GDP in 2019. As a result, the region’s average debt to GDP ratio ballooned from 30 percent of GDP in 2010 to over 45 percent of GDP in 2019. It is little surprise that the region’s most credit hungry countries, Argentina and Ecuador, have already had to renegotiate their onerous debts.

Off the Books, Over the Ledge

This extraordinary fiscal effort is unparalleled in Latin American history. But governments had little choice, since so many of the newly unemployed fall through the cracks of existing social programs. There are exceptions. Uruguay’s total emergency spending is below 1 percent of GDP, as its pre-pandemic welfare system, including unemployment insurance, had wide coverage, thanks to relatively moderate levels of informality. Unfortunately, Argentina is a more typical case for Latin America.

Argentina’s response managed to protect many formal sector workers, including a prohibition on layoffs. (“I’m going to be tough” on businesses, Mr. Fernández said, “because if the pandemic has to teach us anything, it’s solidarity.”) Argentina’s business owners and powerful unions agreed to a reduction of salaries of 25 percent to give firms breathing room as they navigate the crisis. Finally, the government subsidized formal sector employment through its Assistance to Work and Production program, which covers part of workers’ wages. Still, in Argentina and elsewhere, informal workers are bearing the brunt of the economic ruin. After all, prohibitions on layoffs do not help these workers, who also lack protections from union contracts. The results are dramatic: 70 percent of all job losses are in Argentina’s vast informal sector, according to a report by the Social Observatory of the Catholic University. To cover millions of informal workers, Argentina created a temporary basic income program known as the Emergency Family Income, which distributes 10,000 pesos to families per month, or about a fifth of the basic needs for a family of four. Nevertheless, poverty is headed to levels not seen since Argentina’s 2001 economic meltdown.

Red Ink

Latin America is unlikely to see a V-shaped recovery; the scale of the recession this year is unprecedented, even for a crisis-prone region. This means the region’s fiscal accounts will remain in the red for the foreseeable future, as many emergency programs transform into permanent supports.

Given the social needs, that makes sense. There are political rewards, too. Mr. Bolsonaro’s approval rating, for example, has increased in the midst of the world’s second-worst COVID-19 outbreak, thanks in large part to a popular Emergency Aid (Auxílio Emergencial) grant that gives informal workers as much as $120 per month, or 60 percent of the minimum wage. The government’s generous support has caused poverty in Brazil to decline to historically low levels. Seeing the uptick in his approval rating, Mr. Bolsonaro’s hostility to social programs has softened, so much so that he vetoed his own finance minister’s plan to offset new social spending by shrinking other welfare programs, saying, “I can’t take from the poor to give to the poorest.”

But the expansion of welfare programs to the formerly excluded will be burdensome, particularly as rising debt burdens dent credit ratings in the region and raise the cost of borrowing. In the long-term, Latin America’s governments will need to advance reforms to formalize their economies, to generate higher income tax receipts and incorporate workers in traditional pension and social welfare programs. For now, however, continuing to care for informal workers will require tough choices – and all under the looming threat of social outbursts, such as those that convulsed Chile in 2019.

Author

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Argentina Project

The Argentina Project is the premier institution for policy-relevant research on politics and economics in Argentina. Read more

Explore More in Weekly Asado

Browse Weekly Asado

Dengue Haunts South America’s Summers

Lessons from Costa Rica’s Economic Transformation

Women and Latin America’s Digital Revolution