International cooperation is not a means to easy victories, but is necessary to manage intractable problems, share burdens, and avoid disasters. The 70th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War last week is an opportunity to reflect on this truth. That this anniversary should occur in an era of renewed “America first” thinking makes this anniversary all the more pertinent.

Few presidents understood the importance of international cooperation as well as Harry Truman. The newly-sworn in president personally attended the signing ceremony of the United Nations Charter in San Francisco in June 1945, and two days later told an audience in his home state of Missouri that he was “anxious to bring home to you that the world is no longer county size, no longer state-size, no longer nation-size. It is one world . . . It is a world in which we must all get along.”

Truman supported the creation of the UN because he recognized that even though the United States was the only country to emerge from World War II stronger, unilateralism was not in the interests of the United States. The challenges of the post-war world were too great and its problems too complex.

Truman knew this firsthand, because his administration authored some of these problems. His State Department had suggested the joint occupation of Korea in August 1945, hoping a period of joint Soviet-American trusteeship for Korea would ensure the peninsula did not fall into the Soviet orbit. But Koreans were violently opposed to anything short of immediate independence, and the Soviets were unwilling to cooperate on any trusteeship formula besides a communist dominated government.

After nearly two years of trying to compromise with the Soviets and trying to convince Koreans to accept trusteeship, the Truman Administration gave up in the fall of 1947. In an act of desperation, but also wisdom, Truman passed the Korean issue off to the United Nations General Assembly, then meeting in only its second session. An elegant solution quickly emerged: the Korean people should be consulted. The UN created a Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK) to supervise a general election across the peninsula to form a representative Korean government. No US-Soviet compromises necessary. No trusteeship needed. Over the strenuous objections of the Soviet Union and its bloc, resolutions enacting this solution passed easily in the UN general assembly.

The division of Korea could have been solved by UNTCOK in May 1948, but the Soviet Union thwarted UNTCOK at every turn, tried to discredit it as a tool of American imperialism, and refused to let the commission enter its zone. The result was elections in only southern Korea and the creation of the Republic of Korea (ROK).

Truman has been criticized for pushing the issue of Korea onto the UN on the grounds that he unburdened a problem the United States no longer wanted onto an organization that was too weak to bear it. There is some merit to this criticism. The UN was no more able to overcome Soviet intransigence than the US, but the UN did have a store of international legitimacy that both the US and the Soviet Union, because of their growing animosity, lacked. Truman recognized that building a consensus in the UN offered the best hope of success, and the best insurance in case of failure. Korea would no longer be just a US-Soviet problem.

UNTCOK lingered on in the ROK after the elections to seek a permanent solution to Korea’s division. Within hours of the North Korean invasion of the ROK on 25 June 1950, UNTCOK military observers were able to inform the UN Security Council that a full scale invasion was underway and that it had been unprovoked. These reports allowed the Security Council to quickly pass a resolution naming North Korea the aggressor and recommending member states furnish military assistance to the Republic of Korea (ROK).

The United States and 15 other member states answered the Security Council’s call to come to the defense of the ROK. This unprecedented international cooperation did not mean equal burden sharing, nor did it result in a decisive victory. The US and the ROK bore the brunt of the costs of the war in terms of blood and treasure. While the UN intervention surely saved the ROK, China’s entry into the war blunted UN forces attempts to reunite the Korean peninsula and the conflict ended almost exactly where it began three years earlier.

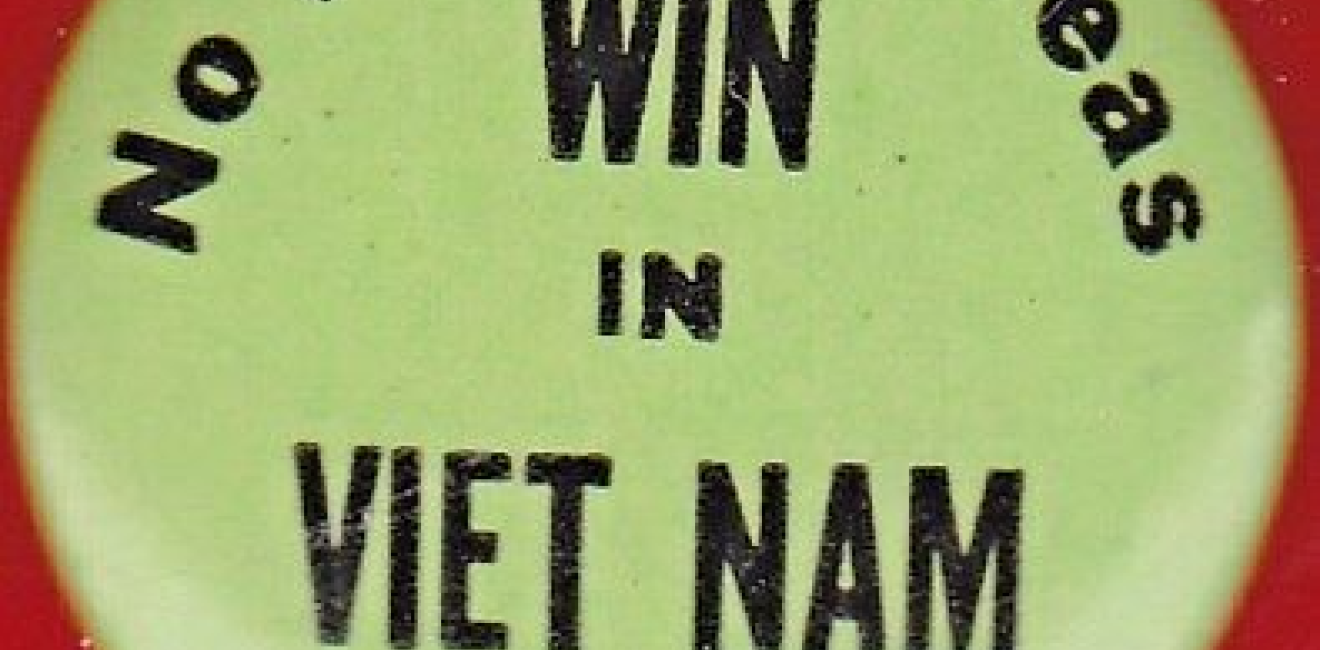

The Korean War was an unprecedented example of international cooperation and collective defense, but this impressed few Americans at the time, especially in the absence of victory. From 1953 through the Vietnam War, which would last until 1975, the Korean War was anything but the “forgotten war.” Before “No more Vietnams” became a slogan of the anti-war movement in the United States, “No more Koreas, win in Viet Nam” was the slogan of those who wanted the US to fight to a decisive victory in Southeast Asia—alone if necessary.

Such slogans failed to grasp that while the outcome in Korea was far from satisfying, worse outcomes were possible. The US spent three years fighting to a stalemate with the backing of the international community in Korea. It would spend more than a decade fighting with far fewer allies in Vietnam with the result being a decisive defeat. The Vietnam War would cost the US much more than Korea by almost any measure. It would also do serious damage to the legitimacy of American leadership.

It takes little imagination to see how a similar disenchantment with internationalism and imperfect solutions propelled Donald Trump into the White House. The international situation in 2016 was full of complex and intractable problems. International trade deals had cost American jobs. North Korea’s continued pursuit of nuclear weapons was frightening. Chinese mercantilism and theft of intellectual property hurt American companies. The nuclear deal with Iran left many issues unaddressed.

The efforts of previous administrations to address these issues was plodding and incomplete. Donald Trump took a different approach: using American power to pressure competitors and allies alike into acquiescing to solutions that placed American interests first—as the administration defined them. After nearly four years it is far from clear whether this strategy has produced any tangible gains, but it has cost the United States in terms of legitimacy and good will with the dozens of alliance partners the United States depends on for its own security and prosperity.

The 70th anniversary of the Korean War highlights the fact that not every international problem has a clear or quick solution, but there is an obvious strategy to deal with such intractable problems: seek allies and build consensus. This was a clear difference between Korea and Vietnam and is a clear difference between policies pursued by President Trump and his predecessors. Such a strategy is not always satisfying. It does not guarantee victory or necessarily provide a perfect solution, but it does ensure the burden will be shared and frequently prevents more costly disasters.