A blog of the Latin America Program

Life in the Villas

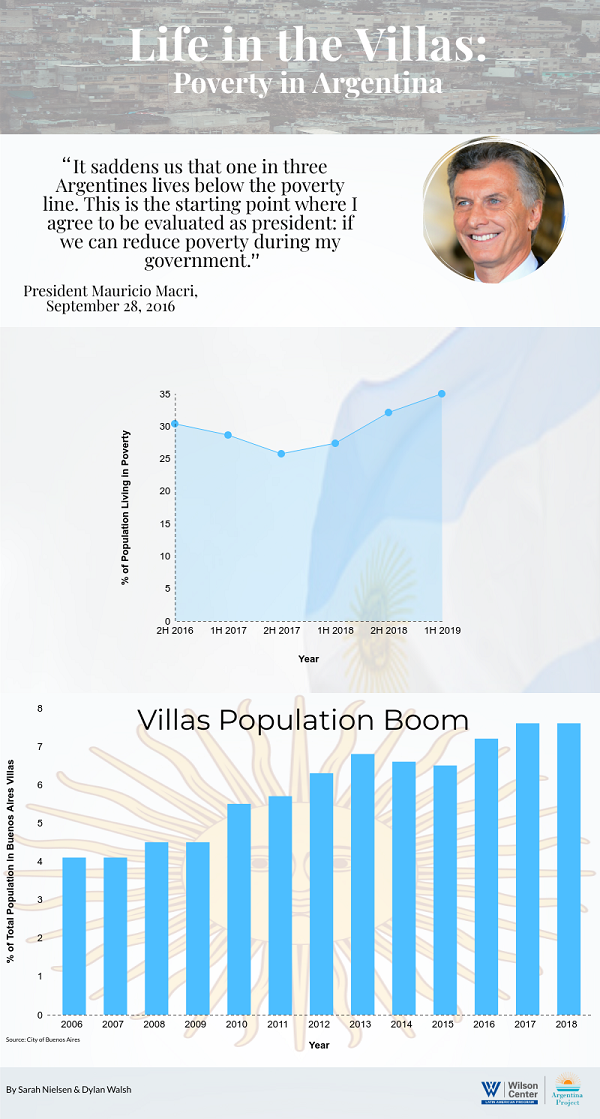

One of President Mauricio Macri’s signature promises in his 2015 campaign was to put the country on a path towards “zero poverty.” That goal, he said, would be the best way to measure his government’s success.

From the start, critics questioned Mr. Macri’s commitment, as the former businessman sought to reduce public spending that had ballooned under his populist predecessors. But he received generous support from international development institutions, including the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank.

Prior to the 2018 crisis, the government saw modest initial success reducing poverty. A showcase of Mr. Macri’s anti-poverty agenda was the revitalization of Villa 31 — Buenos Aires’s largest shantytown, located behind the Retiro railway station, next to Argentina’s richest neighborhood, Recoleta.

Between 2015-2019, the Buenos Aires city government invested over 13 billion pesos revitalizing and urbanizing informal settlements in the capital, including 6 billion for Villa 31. Much of those funds paid for 1,200 new housing units.

The long-term impacts on Villa 31 remain to be seen. But so far, the most direct beneficiaries appear unimpressed.

In Argentina’s August primaries, Villa 31 residents overwhelmingly voted against Mr. Macri and his Cambiemos coalition. The president attracted only 17 percent of the Villa 31 vote, and the Buenos Aires mayor, Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, who spearheaded the ambitious revitalization projects, lost by nearly 47 points to the Frente de Todos candidate, Matías Lammens.

The electoral defeat was no doubt disappointing for Mr. Macri, who has long emphasized infrastructure in his efforts to reduce poverty.

As mayor of Buenos Aires (2007-2015), Mr. Macri also focused on improving living standards in the capital’s slums. In 2011, for example, he created a secretariat of habitat and inclusion (SECHI) to incorporate informal settlements into the city through a policy of “urban acupuncture.” He established community centers, plazas and sports facilities in Buenos Aires shantytowns.

But even then, some critics questioned his approach, pointing to a perceived lack of consultation with community leaders, and complaining about the SECHI’s small budget – $19 million, or less than 1 percent of the city’s budget.

Mr. Rodríguez Larreta extended Mr. Macri’s efforts in 2016 by inaugurating “30 and All,” which also aimed to improve living conditions in Villa 31. During the launch, he said his goal was “to ensure that all neighbors have access to the same quality of services” in education, healthcare, parks, transportation and security.

In addition to investments in infrastructure and housing, Mr. Rodríguez Larreta focused on broader efforts to help Villa 31 residents escape poverty. In 2017, he opened an office of the city government in Villa 31 to be symbolically present in the long-forgotten community.

The city government attracted significant financing and investment for the shantytowns; in 2017, for example, the IDB approved two loans for a total of $550 million for urban integration, social inclusion and education. Recently, the mayor participated in a ceremony as McDonald’s broke ground on its first restaurant in Villa 31 and promised to hire more than 100 local employees.

Ultimately, however, the efforts by Mr. Macri and his protégée in Buenos Aires did not win over Villa 31 voters, who are beset by high inflation and rising unemployment. Workers in Villa 31 labor mostly in the informal sector, with few protections and little ability to renegotiate their wages to keep up with rising prices.

In addition, concerns about gentrification are raising tensions, and drawing criticism of well-intentioned projects, such as a new IDB headquarters designed to create a physical bridge between Recoleta and Villa 31. The conflict has again raised questions about whether the government is doing enough to involve community leaders in the urban planning process.

If the primary election results are any guide, public officials have a long way to go in meeting the needs of Villa 31 and the city’s other informal settlements.

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Argentina Project

The Argentina Project is the premier institution for policy-relevant research on politics and economics in Argentina. Read more

Explore More in Weekly Asado

Browse Weekly Asado

Dengue Haunts South America’s Summers

Lessons from Costa Rica’s Economic Transformation

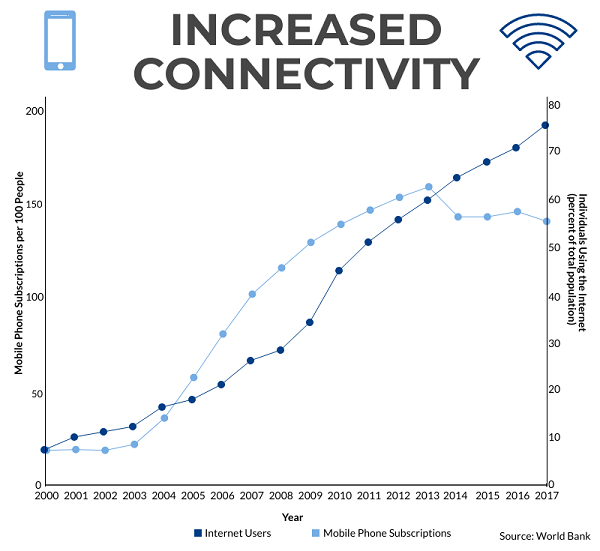

Women and Latin America’s Digital Revolution