New Discoveries and Implications from the Records of the Historic Sino-Japanese Meetings in 1972

In 1972, Japan's leaders underestimated significance of moral and emotional elements in Sino-Japanese relations.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

In 1972, Japan's leaders underestimated significance of moral and emotional elements in Sino-Japanese relations.

How Japan's leaders underestimated the moral and emotional elements of Sino-Japanese relations

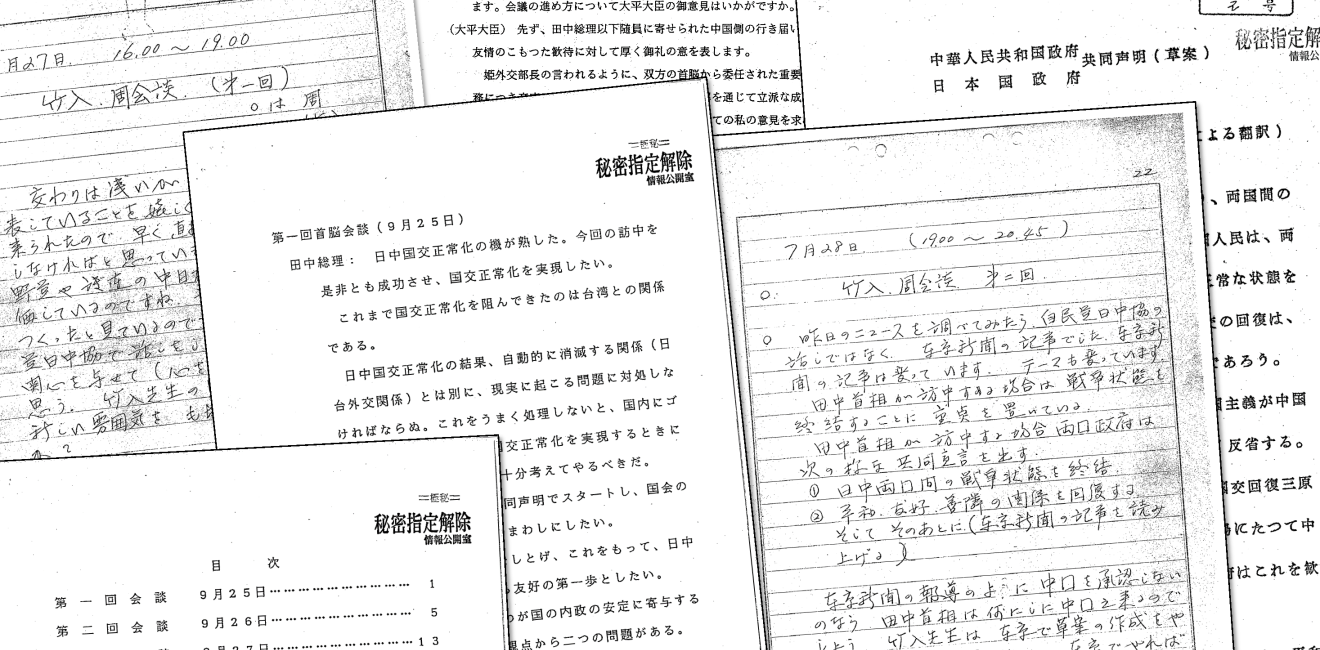

The newly published records of the historic meetings between Japanese and Chinese leaders unveil the very last phase in the process of the normalization of Sino-Japanese diplomatic relations in 1972.

Readers can clearly see the personalities of two nations’ leaders. Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, particularly in his discussion with Japanese Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei, showed his broad view of international affairs as well as his detailed knowledge of Japanese internal politics, even though there were no official connections between Tokyo and Beijing by that time.

On the other hand, Tanaka repeatedly emphasized his difficulties in persuading anti-PRC, pro-Taiwan lobbyists in his Liberal Democratic Party that Japan should establish ties with Beijing. This might have been a typical diplomatic tactic so as to make the Chinese believe in Japan’s inability to compromise, but it also indicates that the China question was more a domestic issue than an international one in the minds of the Japanese leader.

Not surprisingly, Zhou Enlai’s statements in these records show that the primary external concern of the Chinese was the threat of the Soviet Union. While it is debatable whether it was necessary or not, Zhou unilaterally made a long speech to Tanaka and his Foreign Minister Ohira Masayoshi offering a detailed history of the Sino-Soviet split.

Interestingly, Tanaka did not conceal from Zhou his hatred of Moscow, even though the United States—Japan’s principal ally—avoided taking sides with either Beijing or Moscow at that time. At the end of Zhou’s long speech, Tanaka agreed with Zhou’s position, stating that Japan did not trust the Soviet Union because “they kicked open the gallows’ trapdoor,” referring to Soviet participation in the war with Japan in August 1945. The Chinese side seemed to be impressed with Tanaka’s attitude. Chairman Mao Zedong later cited this metaphoric expression from Tanaka in his conversation with Henry Kissinger in 1973.[1]

In the Joint Communique of Japan and China published on the last day of Tanaka’s visit, they agreed that “both countries will oppose other countries or groups of countries that seek to establish hegemony,” which many people, including the Russians, interpreted as implicitly declaring their common anti-Soviet stance. Tanaka’s successors had to make every effort to deny such implications of this agreement.

Yet, as these records show, it is impossible to believe that Tanaka and Ohira accepted this clause in order to stand together with the Chinese against the Russians. To be sure, Tanaka was personally anti-Soviet, and his administration was not eager to approach Moscow after constructing ties with Beijing.

However, on the basis of these records, it would be more natural to consider that the Japanese side accepted this clause only because they failed to understand the implications of this phrase, whereas the Chinese did not intend to demand it strongly. As early as two months before Tanaka’s visit to China, Zhou told Takeiri Yoshikatsu that if “the wording of the section on hegemony is thought to be too strong…we will not have anything to include,” indicating that the Chinese side was even ready to compromise if Japan wished to avoid being involved in China’s strategic position. Also, in the negotiations between the Chinese and Japanese foreign ministers, it was Ji Pengfei who suggested to add the phrase “Japan-China relations is not exclusive, and that it is not aimed at a third country” to the “anti-hegemony” clause. Oddly, to Ji’s suggestion, Ohira responded by saying “We are not particular about this.” Ohira seemed unaware of the implications, while the Chinese were even more sensitive than the Japanese to the effect of this statement on the Japanese strategic position.[2]

The Taiwan problem, which had generally been an extremely sensitive issue for the Chinese, did not cause difficulties during the process of normalizing Sino-Japanese relations. The Japanese idea of establishing the new “citizen-level” relations between Tokyo and Taipei was smoothly accepted by the Chinese side. After hearing Ohira’s plan for new Japanese-Taiwanese relations after the breakup of diplomatic ties, the Chinese side “all looked relieved” and Zhou even recommended that Japan “take the leadership role and establish an office in Taiwan first.”

According to these descriptions, it might even be possible to imagine that the Chinese had expected the Japanese to be more demanding on this issue. Zhou and his followers might have been ready to negotiate, or even compromise to some extent, with Tanaka and Ohira. Of course, we need to wait for the Chinese records to be disclosed so as to know what exactly the Chinese position on the Taiwan question was.

Although there were frictions over Tanaka’s “embarrassment” speech, the “history problem” was not as major an issue as it would be in later decades. However, it is significant to note that the Japanese side “hope[d] that problems relating to the liquidation of abnormal relations between Japan and China in the past, including war, should all be solved by this conversation and its result, the Joint Statement, thereby leaving no backward job in the future.”

Already in 1972, the Japanese understood the potential seriousness of the “past” issue, and believed that it was possible to block the beginning of the history problem only by agreeing the Joint Statement. This implies that, as was common in later decades, Japanese leaders overestimated the power of legal agreement in diplomacy, whereas they underestimated the significance of moral and emotional elements in Sino-Japanese relations.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more