A blog of the Latin America Program

Pandemic Tipple

By Lucy Hale

Argentina imposed one of the world’s longest pandemic lockdowns, a disruption that devastated critical sectors of the economy. The country’s iconic wine industry was not among them.

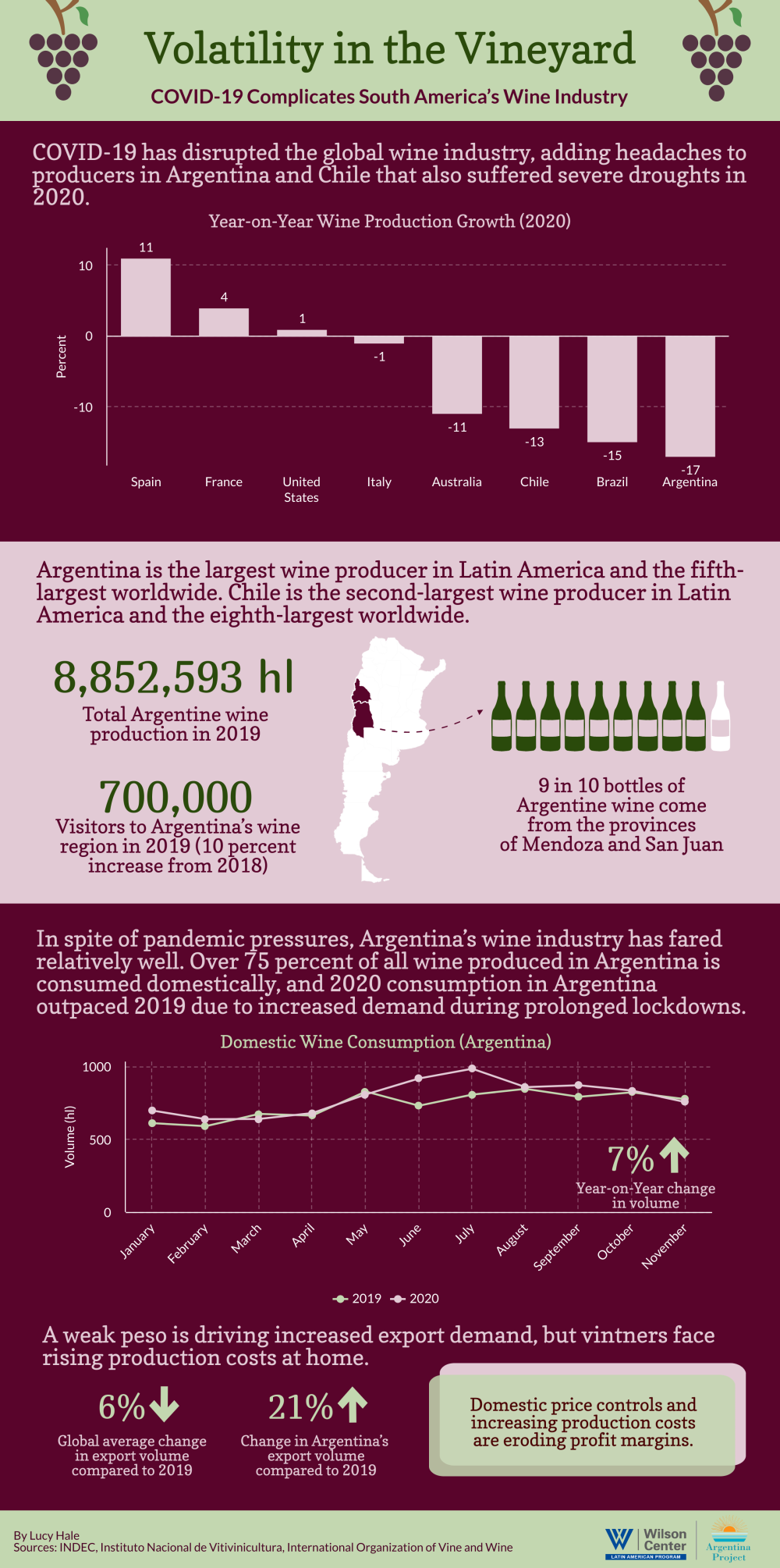

Wine consumption in Argentina was 7 percent higher in 2020 than in 2019, as homebound Argentines sought ways to fight the coronavirus gloom. That was a godsend for winemakers. In contrast to neighboring Chile, Latin America’s second-biggest wine producer, which exports three quarters of its wine production, Argentina sells only a quarter of its wine abroad. Given the Italian and Spanish roots of many Argentines, “wine is part of the dinner table in Argentina,” Juan Carlos Pina, executive director of the industry association Bodegas de Argentina, said in an interview.

The country’s wine exports also performed well in 2020, boosted by a rapidly depreciating peso. Though the sector is not a major employer, the government has pointed to its performance as a potential driver of post-pandemic recovery. In all, the volume of Argentine wine exports grew by 21 percent from January to November, compared to a global decline of nearly 6 percent, according to Argentina’s Instituto Nacional de Vitivinicultura. Argentina was the only South American country to experience an increase in export volume in 2020; Chile’s export volume declined by 13 percent between January and August.

The industry’s performance does not reflect broader trends in Argentina, where the economy contracted in 2020 by an estimated 10 percent. But the wine sector is symbolically important, given the beverage’s centrality to Argentina’s culture and global image. Argentina is Latin America’s top wine producer, and the fifth largest in the world. Its wine growing region, in Andean mountain valleys, is often compared to California’s Napa Valley. The provinces of Mendoza and San Juan, the country’s wine powerhouses, are internationally known for Malbec as well as Bonarda, Syrah and Cabernet Sauvignon.

Special treatment from the national government has helped insulate winemakers from the economic tumult. In an interview, Francisco do Pico, of Grupo Peñaflor, praised Argentina’s designation of winemaking as an essential activity, which allowed most of Argentina’s wineries to operate uninterruptedly throughout the year despite lengthy national COVID-19 lockdowns. Chile also designated winemaking as an essential activity and imposed salary protections to support temporary farmworkers.

Despite Argentina’s robust domestic sales and growing exports, however, 2020 brought significant challenges for its wine producers. The collapse in tourism, for example, cut into revenues for large and small wineries alike. Large wineries often rely on tourism to increase brand recognition and draw customers to upscale vineyard restaurants. For many smaller producers, tourism is a critical sales channel. In 2019, Argentina’s Mendoza province attracted a record number of tourists, nearly 700,000, a 10 percent increase from 2018. For much of 2020, however, Argentina kept its borders closed and even restricted domestic travel.

To take advantage of pent-up demand for travel, the Argentine and Chilean tourism ministries are jointly organizing the “longest wine route in the world,” a boozy, 800-mile expedition from La Serena, Chile to Santiago Del Estero, Argentina. But for now, as Argentina and Chile endure a second wave of the virus, a tourism rebound seems distant. Some winemakers are making use of underutilized facilities to support pandemic response, such as Viña Concha y Toro, which owns 56 vineyards in Chile and ten in Argentina and has adapted its research laboratory to process COVID-19 tests.

Even before the pandemic, Argentina’s wine industry was warning of diminishing profitability. Though Argentines are drinking more wine, price controls for popular vinos de mesa are cutting into revenues. That has made it difficult to pass on increasing production costs to consumers, including the rising price of transportation, Magdalena Pesce, of the industry association Wines of Argentina, said in an interview. South American winemakers are also harmed by increasingly unfavorable weather conditions related to climate change. Although harvests were largely uninterrupted by pandemic lockdowns, both Argentina and Chile saw double digit declines in production volume in 2020 as a result of drought conditions.

Now, the worsening pandemic is threatening potential labor shortages, should new travel restrictions deprive Argentina of temporary laborers, including Bolivians, during the grape harvest that began this month. Anticipating a scarcity of workers, Mendoza is recruiting 10,000 unemployed provincial residents to register for farm labor.

Still, all in all, given the economic wreckage in most other Argentine industries, the pandemic performance of Argentina’s winemakers remains the toast of the town.

Author

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Argentina Project

The Argentina Project is the premier institution for policy-relevant research on politics and economics in Argentina. Read more

Explore More in Weekly Asado

Browse Weekly Asado

Dengue Haunts South America’s Summers

Lessons from Costa Rica’s Economic Transformation

Women and Latin America’s Digital Revolution