PDD-25 and the Genocide in Rwanda: Why Not a Task for the United States?

According to newly uncovered files at the Clinton Library, American policies in Somalia and Rwanda were parallel rather than consequential.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

According to newly uncovered files at the Clinton Library, American policies in Somalia and Rwanda were parallel rather than consequential.

Newly uncovered files at the Clinton Library suggest there was no linkage between the US experience in Somalia and its reluctance to later intervene in the Rwandan genocide

I believe the historical evidence clearly demonstrates that peacekeeping is not a task for the United States.

These are the words of former CIA analyst Frederick Fleitz, from his book Peacekeeping Fiascoes of the 1990s. By many accounts, Fleitz’s statement captures America’s experience with UN missions and broader relations during the 1990s.

The successful US action under the UN umbrella in 1991’s Operation Desert Storm generated much enthusiasm that the United Nations could finally become an efficient mechanism, at disposal of the United States, to settle international crises. In 1993–1994, however, a series of events tested America’s commitment to peacekeeping missions and humanitarian interventions.

Most notable was the death of 18 US soldiers on October 3, 1993, during a long and devastating battle in Mogadishu, Somalia. Gruesome images of a dead American soldier being dragged through the city’s streets by a jubilant crowd shocked the US public. This incident, often remembered as “Black Hawk Down,” provoked President Bill Clinton to withdraw troops from the UN intervention in the Somali civil war and humanitarian crisis by the end of May 1994.

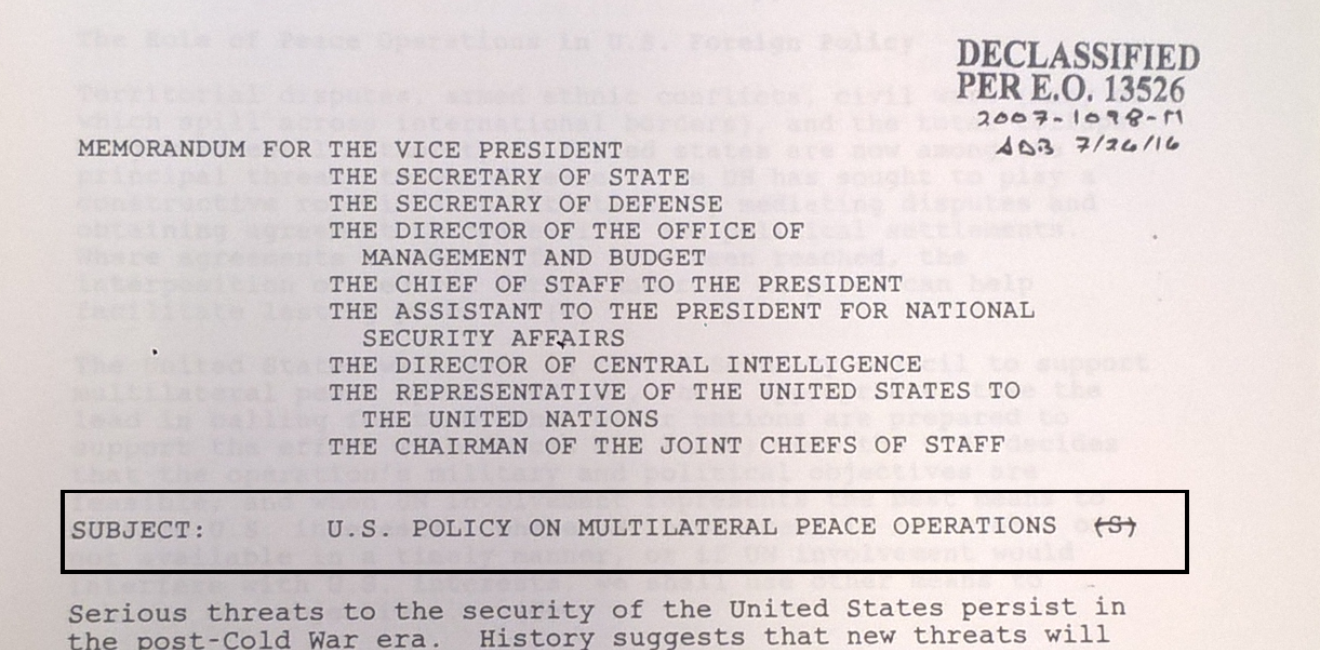

Earlier in February 1993, the Clinton Administration had launched a review of US participation in peacekeeping operations. This process ended on May 3, 1994, with the release of Presidential Decision Directive 25 (PDD-25). The document established onerous requirements on US support for and participation in UN peace operations abroad.

Not long thereafter, when a brutal genocide took place in Rwanda in April 1994, Washington maintained a very low profile and showed a reluctance toward any UN attempt to intervene and halt a massacre that eventually caused 800,000 deaths.

A “linkage” between these developments seemed clear to all observers. The “fiasco” in Somalia cooled down America’s appetite for involvement in other UN peacekeeping missions and produced the restrictive criteria of the PDD-25. US inaction during the Rwandan genocide was a direct consequence of the experience in Somalia and became emblematic of Washington’s U-turn from previous commitments to UN multilateral interventions.

However, newly declassified documents produced in the 1990s do not substantiate the “linkage” theory. In fact, they depict a very different scenario.

The Clinton Presidential Library has recently declassified one of the earlier drafts of PDD-25, produced in September 1993, several weeks before the Black Hawk Down incident. A comparison between this draft and the final version of PDD-25 released in May 1994 clearly shows that the events in Somalia in October 1993 did not really influence the content of PDD-25. Its strict guidelines were already on paper and part of American peacekeeping policy prior to the fiasco in Mogadishu.

More importantly, some Department of State files show how in July 1993 the Clinton Administration evaluated the possible deployment of a UN mission to Rwanda using the provisional first draft of PDD-25 during the earliest stages of the crisis. This indicates that the criteria contained in PDD-25 had become an integral part of the decision-making process for American policy in Rwanda long before the Mogadishu incident.

In sum, there is no linkage.

What happened in Somalia in October 1993 undoubtedly affected the Clinton Administration’s willingness to be involved in another complex crisis in Africa. However, it was certainly not the impetus for the restrictive language of PDD-25, nor the reason for inaction in Rwanda.

If, as Fleitz claims, peacekeeping is not a task for the United States, the “historical evidence” for this statement is to be found before the Mogadishu disaster.

The withdrawal from UN missions was part of the broader reformulation of Washington’s relations with the United Nations after the Cold War. In the aftermath of the Gulf War, President George H.W. Bush talked about the advent of a "New World Order" in which the United Nations could finally "performs as envisioned by its founders." A few years later, the Clinton Administration coined the concept of “assertive multilateralism” to promote a foreign policy based on multilateral engagement and US leadership within collective bodies, primarily the United Nations.

However, a more attentive analysis of these ostensibly optimistic and positive approaches and policies demonstrates that they actually already encapsulated the seeds and assumptions of the restrictive criteria of PDD25. In this sense, the Rwandan crisis did not signal a dramatic change in US peacekeeping policy, one which started in Somalia and was sealed by PDD-25. Rather, Rwanda was consistent with a longer-term pattern that had characterized American foreign policy since the early 1990s.

American policies in Somalia and Rwanda were parallel rather than consequential. Revisiting their linkage is the first step to correct an historical inaccuracy.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more