A blog of the Kennan Institute

Just ten years ago it would have been hard to imagine that the crackdown on civic activism in Russia would target religious communities, not just NGOs. And yet it is happening. The Russian state persecutes Baptists, Pentecostals, and Adventists and closes down Orthodox parishes that are not part of the Moscow Patriarchate. For the first time since the Soviet Union collapsed, preachers are now being fined for proclaiming God’s word outside church buildings. And a recent Supreme Court decision has opened the door to liquidating Jehovah’s Witnesses communities in Russia.

“Traditional” versus “Nontraditional” Religions

Russia divides all faiths into “traditional” and “nontraditional.” This concept, while absent from the Russian Law on Religious Freedom (although mentioned in the law’s preamble), has been introduced under pressure from the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) and Patriarch Kirill personally. Orthodox Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and Buddhism are deemed “traditional,” while Old Believers, Catholics, various Protestant denominations, and many others are not.

The concept of traditional religions not only pits worshippers against each other, it also ignores the religious diversity of Russia. Today there are some 15 million practicing Orthodox believers in Russia, 10 million Muslims, 3 million Protestants, 500,000 Buddhists, 200,000 Jews, 175,000 Jehovah’s Witnesses, 100,000 Hindus, and 100,000 followers of other religious faiths (e.g., there are an estimated 10,000 Mormons in Russia).

The ROC has usurped the right to a close relationship with the government and accuses Catholics and Protestants of proselytizing in the territory that it considers its own. As for Muslims, the ROC accepts as “traditional” only those who are loyal to the government.

The ROC’s concern is understandable. According to the Russian Ministry of Justice, ROC organizations are the most numerous in the country (around 16,000 communities), while Protestants and Muslims are second and third (5,000–6,000 communities each).

However, polls show that Protestants and Muslims may be twice as numerous as official figures suggest. For example, evangelicals are now the second largest Christian denomination in Russia after Orthodox Christians in terms of numbers and presence throughout the country. In fact, in many regions of Siberia and the Far East, the number of Protestant communities and active parishioners is higher than the number of practicing Orthodox believers. In light of this, Patriarch Kirill has repeatedly urged the authorities in the Far East to “fight against sects” and support the Orthodox projects.

Tightening the Screws

The path toward tightening the screws on various nontraditional religions began in 2012, with the “foreign agent” law limiting the activity of foreign-funded noncommercial organizations. Furthermore, the law on meetings and demonstrations was also tightened. And in 2015 a new directive was introduced specifying that all religious groups must inform authorities of their existence.

Then, in June 2016, the State Duma adopted a series of laws known collectively as the Yarovaya Law. Named after Duma Deputy Irina Yarovaya, who initiated it, the law amends Russian public safety and anti-extremism legislation. The part of the law that has already come into force and has received the broadest coverage consists of the statues regulating liability for failure to report “extremist activity”—a very broadly defined set of activities under Russian law, ranging from calls for violence to the vague “incitement of racial, nationalist and religious hatred” and “propaganda of exceptionalism” based on religion or nationality.

The part of the Yarovaya Law that has received much less attention is the provision imposing new restrictions on missionary work. The law now imposes a fine of 50,000 rubles on a private citizen for illegal preaching and up to 1 million rubles on a religious organization. Illegal preaching may mean preaching in a building that is not designated for such purposes and lacks proper signage. As a result, the police and the prosecutor’s office now consider the activity of religious groups lacking official registration as illegal—a change from the recent past.

Targeting Jehovah’s Witnesses

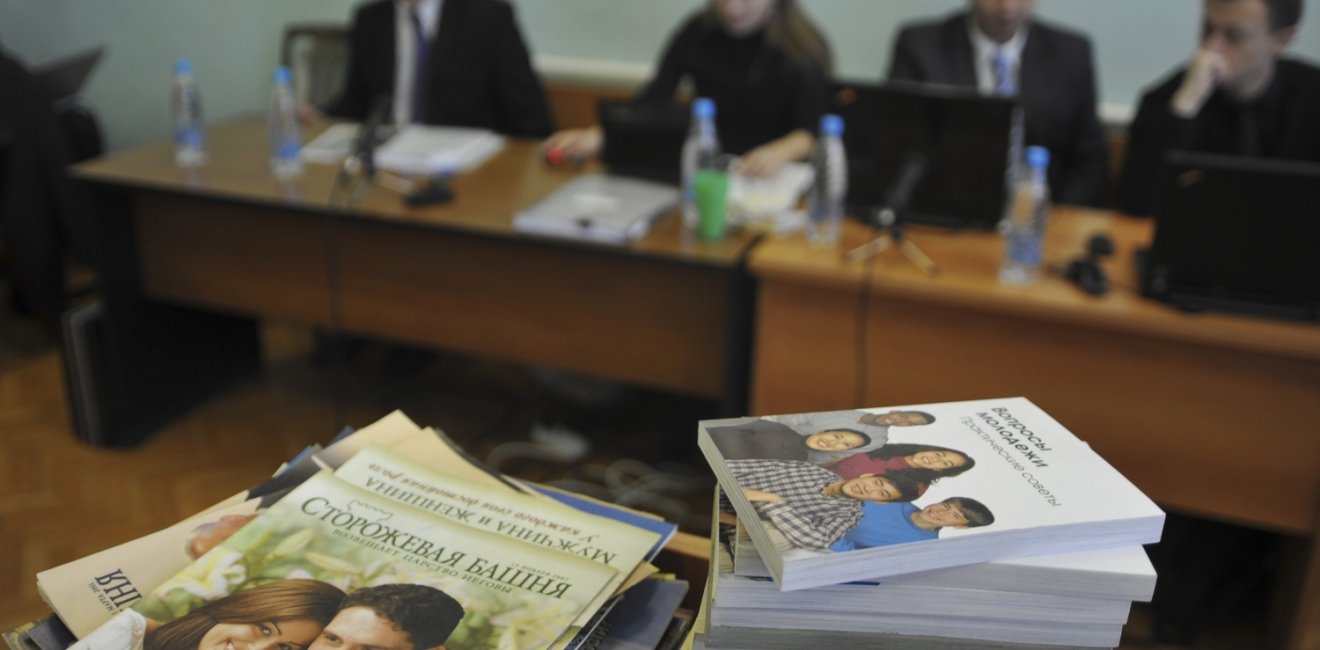

The recent court proceedings against Jehovah’s Witnesses are a case in point. The campaign against Jehovah’s Witnesses began in 2009, during the still relatively liberal Dmitry Medvedev’s premiership. In a number of cases the courts, relying on poorly and unprofessionally conducted evaluations, concluded that Jehovah’s Witnesses’ literature could be defined as “extremist,” referring as it did to the faith as the only true faith.

The adoption of the Yarovaya Law, therefore, opened the door to liquidating Jehovah’s Witnesses communities on the basis of their possessing “extremist” literature.

On April 20, 2017, on the basis of the totality of these cases, the Russian Supreme Court ruled to liquidate the Jehovah’s Witnesses Management Center and all of the regional organizations. On July 17, 2017, a Supreme Court panel declined the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ appeal, and the decision entered into force.

The decision means prohibition of activity for over 400 Jehovah’s Witnesses organizations all over Russia and criminal prosecutions of more than 170,000 believers if they continue to gather and read faith publications and the Bible in their specific translation. (There are more than 2,000 groups engaged in this activity in Russia.) On top of that, because Jehovah’s Witnesses organizations are now judged “extremist,” the state is confiscating the profession’s assets: 118 buildings in fifty-seven regions whose total value is 1.9 billion rubles.

For the West, it was specifically the prohibition against Jehovah’s Witnesses that came to symbolize pointless religious discrimination in Russia and a drastic reduction of religious freedoms in the country. The EU’s Office of Foreign Policy, the U.S. State Department, and the U.S. Helsinki Committee have all broadly criticized the move and called on Russia to rescind it.

On top of that, Jehovah’s Witnesses has filed a complaint with the European Court of Human Rights. It is clear in advance that the judgment won’t be in Russia’s favor. Taking into account the losses sustained by the faithful, the fine that the Strasbourg court will impose on Russia for the benefit of Jehovah’s Witnesses may reach astronomical heights.

The fact is, authorities’ fight against nontraditional religions and religious denominations, which they peg as weird and scary sects, takes ugly, almost caricature forms. Journalists, politicians, and Orthodox activists accuse those of other faiths of activities that constitute the core religious activities of all faiths, including the ROC itself: collecting donations, engaging in prayers with emotional overtones, and instructing followers, including children, in the tenets of the faith. In the context of the massive anti-West hysteria, xenophobia, and search for spies, all of these generally normal activities become a crime.

Most politicians and public figures, both conservative and liberal, readily jump on the bandwagon, portraying unfamiliar “sects” as threatening to the secular state and even citizens’ psychological health. And the media ignore the persecution of those targeted under the Yarovaya Law. There are now more than 100 court cases challenging the imposition of fines against religious communities and individual faithful, yet they are proceeding unnoticed by the general public.

Who Benefits?

Many assume that the suppression of religious dissent automatically benefits the ROC. But that is not necessarily the case. Representatives of the Moscow Patriarchate are torn by irreconcilable contradictions. On the one hand, there are those who would like to prohibit all sects legislatively and in that way eliminate all competitors. (They are particularly troubled by the evangelicals in the Far East, who at this point exceed the number of the Orthodox.)

On the other hand, many experts note that as soon as the word “sect” is introduced into the law, half the Orthodox communities could be prohibited. Rank-and-file priests and believers have stated that the antimissionary statutes of the Yarovaya Law could also be used to prevent Orthodox sermons and missions among youth.

In Russia, the gap is growing between the discriminated-against non-Orthodox Christians and the Orthodox, between the ROC bureaucracy and Orthodox activists of different persuasions, between the ROC’s leadership and the pro-democracy-minded part of society, between the desires of law enforcement organs and the aims of the missionaries of different churches, including the ROC.

These conflicts are getting sharper because Russian society betrays more civility than the Russian state. Ordinary Russians are much more tolerant of those professing different beliefs than are the police and the prosecutor’s office. And the trend toward aligning the government’s policy with the interests of the ROC produces a boomerang effect: civil society criticizes priests and bishops from the Orthodox standpoint, not from an atheistic one. This is why the state has decided to safeguard itself against independent religious authority by heavily regulating it.

Author

Senior Researcher, Institute of Philosophy, Russian Academy of Sciences

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in The Russia File

Browse The Russia File

Chechnya as a Model of Modern Russia

Russia’s Indigenous Communities and the War in Ukraine

Gas and Power in a Changing US–Russia Relationship