A blog of the Kennan Institute

BY ANDRIAN PROKIP

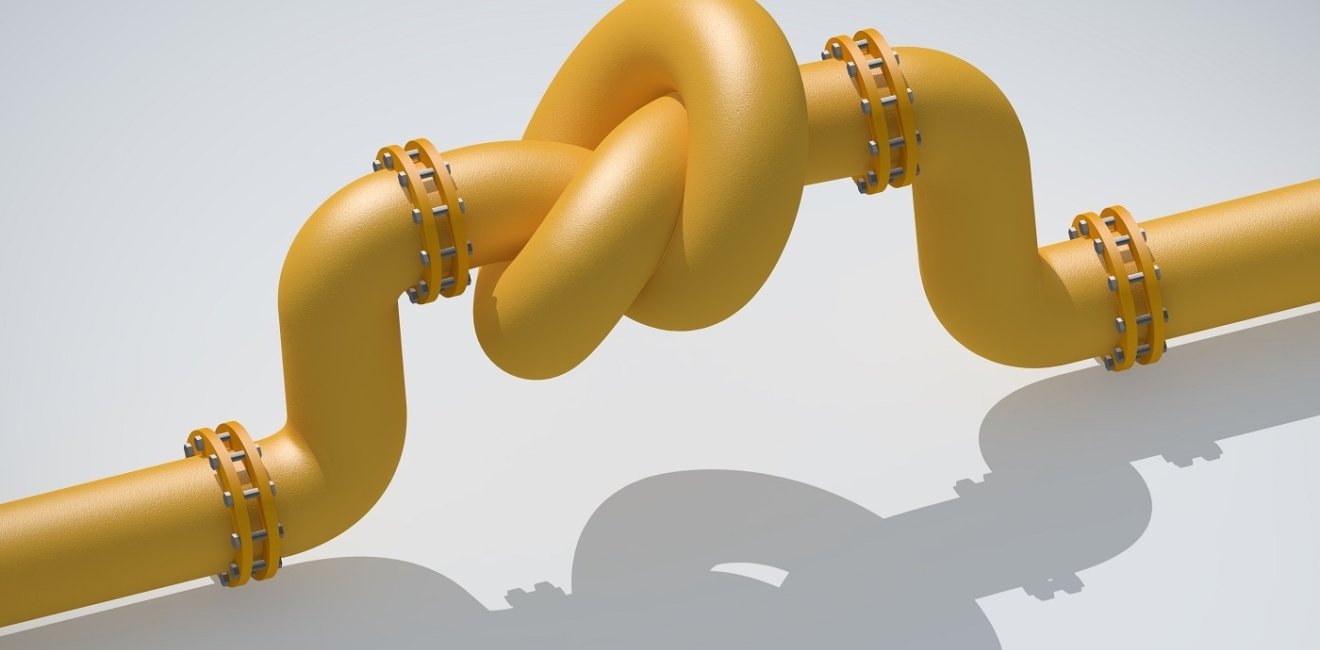

After Russia launched a full-scale military invasion of Ukraine on February 24, Europe’s dependence on fossil fuels from Russia became an issue of top importance. After the immediate tit-for-tat in response to Western sanctions, Russia has moved on to more serious wagers on its blackmail menu, requiring payment in rubles and preparing to use fuel transit as its latest bargaining chip. It has imposed sanctions against Poland’s pipeline and sabotaged Ukraine’s transit infrastructure, either of which would be almost necessary to continue flowing gas to Gazprom’s European customers, then claimed that “bottlenecks—of its own creation—are preventing the fulfillment of contractual obligations. The political one-upmanship that Russia is playing with Ukraine over gas transit adds another important dimension to what has the taint of crooked dealing.

Russia Raising Its Bets

The invasion of February 24 ignited a quick EU-Russia confrontation in energy relations. The EU approved an embargo on Russian coal and started discussions on restricting gas and oil imports. The German government took control of Gazprom’s subsidiary in that country, Gazprom Germania GmbH, with the goal of safeguarding energy supplies against the Kremlin’s whims, according to economic minister Robert Habeck. Germany also launched an investigation to determine whether the subsidiary had been manipulating the market to affect prices last year. The UK is considering the same step, taking over a British subsidiary of Gazprom, after a nontransparent change in ownership.

Russia then demanded that “unfriendly states” pay for energy supplies in rubles, which could violate EU sanctions and, critically, threaten the entire settlement procedure, leaving counterparties to contracts for Russian gas unable to defend themselves in court. Bulgaria refused to accede to that demand, as did Poland, which earlier had imposed sanctions against Gazprom. Russia announced the suspension of gas supplies to these countries, a move that President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen characterized as energy blackmailing by the Kremlin. On May 21, Russia halted natural gas exports to Finland after that country announced it wanted to join NATO.

Earlier, on May 11, Russia imposed sanctions against thirty-one companies operating in Europe, including former Gazprom subsidiaries now controlled by European national governments, which means those thirty-one entities are now unable to conduct trade operations. The Austrian government threatened Gazprom with nationalizing its gas storage, one of the biggest in Europe, if the subsidiary does not meet its contractual obligations. Last year Gazprom’s failure to fill German storage facilities contributed to the rally in gas prices in Europe. Germany is now similarly considering nationalizing Russian assets in Germany.

Europe has sought to restrict Russian energy supplies as a way to rein in the Kremlin’s aggressive militarism and to decrease Europe’s own energy dependence on Russia. Russia, for its part, has worked hard to convey the message that Europe cannot survive without Russian fossil fuels. But the confrontation may ratchet up soon as Russia tries to block some gas transit corridors, of a piece with its overall blackmailing gamble.

Russia’s Gas Deliveries to Europe

In 2021 Russian pipeline gas exports amounted to 210 billion cubic meters (bcm), most of which traditionally went to Europe, along with 40 bcm of liquefied natural gas (LNG), making Russia the fourth largest global exporter of LNG. Gazprom was to supply 183 bcm to Europe, including Turkey, but delivered only 177 bcm. To do so, Russia used a few established transit routes:

- The Ukrainian route, the oldest one, with a 146 bcm annual transit capacity;

- The Yamal-Europe pipeline, which passes through Belarus to Poland and Germany and has a 33 bcm capacity;

- The Blue Stream pipeline, which passes under the Black Sea to deliver gas to Turkey and has a 16 bcm capacity;

- Two legs of TurkStream, which deliver gas to Turkey and on to some southeastern European states and jointly have a capacity of 31.5 bcm (in operation since 2020 and 2021); and

- Nord Stream 1, comprising two pipelines that pass under the Baltic Sea to deliver gas to Germany, with a combined capacity of 55 bcm (in operation since 2011).

Last year, 58 bcm of Russian gas reached the EU through the Nord Stream 1 pipelines, 37 bcm through Ukraine’s pipelines, 33 bcm through the Yamal-Europe pipeline, and 9 bcm through Turkey; an additional 16 bcm were delivered as LNG.

Hence the lion’s share of exports goes through two countries currently experiencing bad relations with Russia and trying to distance themselves and decrease their dependency on energy imports, Poland and Ukraine. And Russia has preferred to use both these countries’ pipelines as little as possible. In 2021 the Belarus-Poland route (Yamal-Europe pipeline) transited 8.6 percent less than in 2020, and the pipelines through Ukraine transited 12 percent less, while other routes transited at the same level or higher.

When the war started, Germany refused to certify the Nord Stream 2 pipelines, which were almost ready to be operationalized. If Russia chose to, it could halt transit either through Poland or through Ukraine, but not both, and still deliver gas to the EU. In mid-May, Russia banned use of the Yamal-Europe pipeline, a move intended to apply political pressure on Belarus, which lost transit revenues. The war has caused major problems with using the Ukrainian route, but here a different political chess game is playing out.

Ukrainian Transit during the War

For some time after February 24, gas transit through Ukraine remained stable. The ongoing transit of energy supplies from an invading country through the country being invaded confused many in Ukraine and abroad. Another puzzling factor was that at times, the volumes transited were higher than the minimal volumes agreed on. Russia may have speculated that Ukraine would be happy to realize some transit revenues despite the invasion.

But if Ukraine itself were to halt transit despite the contracts with Europe to deliver gas, it could be interpreted as a form of blackmail, as an attempt on Ukraine’s part to pressure Europe into speeding up the imposition of sanctions. Such an explanation for the ongoing transit of Russian gas was subsequently forwarded by Ukrainian representatives, who said that Ukraine would stop the transit if Russia’s European customers said they did not need that gas.

Thus Ukraine continued to transit Russian gas during hostilities, in the face of clear and present danger. On March 10, however, Russian forces invaded the gas transit facilities in Luhansk and Kharkiv oblasts and interfered with the equipment, threatening transit operations. More such actions were reported later. Ukrainian representatives warned that damaging these facilities could cut existing transit capacities by 30 percent. And Naftogaz reasonably suspects that pro-Russia separatists in Donbas have been stealing gas.

On May 10, Ukraine sent Gazprom a force majeure memo notifying that Ukraine was unable to transit gas through the occupied territories because of interference from the occupiers and proposed using other entry points to maintain the volumes of gas transited. Russia refused, saying that the alternatives were technically impossible, but Ukraine showed the falsehood of this argument.

What’s Next?

If Russia wants to maintain adequate transit capacities, it has options: it could protect Ukrainian infrastructure from interference, it could use alternative Ukrainian pipelines, or it could refrain from imposing sanctions on Poland and banning use of the Belarus-Poland route. Instead, Russia is whitewashing the situation and its role in the energy crisis by claiming it is unable to use Ukrainian and Polish routes.

All of this may be merely preparing the ground for a new round of gas wars and a new effort to erode EU opposition through energy blackmail. Moreover, with reduced Russian gas supplies reaching Europe, there may be another rally in gas prices, which would help Russia’s coffers. Russia could also cite “bottlenecks” in the Ukrainian and Polish routes as a reason to push for using the Nord Stream 2 pipelines. Unfortunately, all that is happening now with respect to EU-Russia energy relations is basically a result of not learning lessons from the past about energy dependence, something I discussed in a previous Focus Ukraine column.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.

Author

Director, Energy Program, Ukrainian Institute for the Future

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Wilson Center is proud of its historic connection to the Kennan Institute and looks forward to supporting its activities as an independent center of knowledge. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in Focus Ukraine

Browse Focus Ukraine

Talking to the Dead to Heal the Living

Ukrainian Issue in Polish Elections