A blog of the Latin America Program

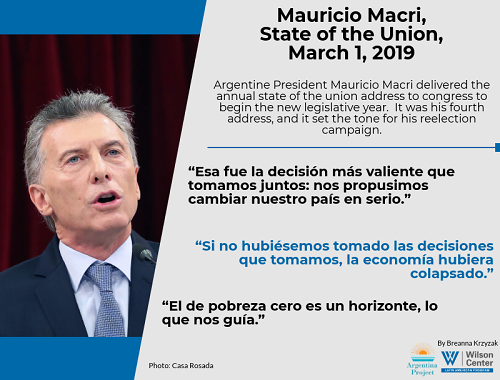

On March 1, Argentine President Mauricio Macri delivered the annual state of the union address to congress, a speech designed to highlight the achievements of his presidency since coming to office in December 2015. But according to polls and the opposition response, it appears the speech spoke mainly to the president’s base. That’s a problem; Mr. Macri is running for reelection in a hotly contested race, and he needs to expand his electoral coalition to be competitive against his archrival, former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, and a potentially formidable traditional Peronist candidate, such as former Finance Minister Roberto Lavanga.

In his remarks, Mr. Macri’s core message was, “Argentina está mejor parada que en el 2015.” In his judgement, Argentina is a stronger democracy, which welcomes a “pluralidad de voces” in politics and the media; enjoys improved infrastructure; and has recaptured a leadership role, “en la region y en la escena global,” as demonstrated by its hosting late last year of the G-20 summit, its protaganism in the Lima Group in addressing the Venezuela crisis, and Mr. Macri’s 130 meetings with leaders from 48 countries.

On the other hand, there is the economy. Mr. Marci’s gradualismo strategy faltered last year, as a run on the peso spiraled into a recession and steep devaluation. GDP declined by 2.6 percent last year, amid soaring inflation. The crisis forced the government to increase sharply interest rates and negotiate a $57 billion International Monetary Fund bailout that requires painful budget cuts and tight monetary policy. In his state of the union, Mr. Macri did not ignore these unfortuante events: “Todo nos agarró a mitad de camino, porque recién estábamos saliendo,” he said.

Indeed, Mr. Macri said, the currency crisis had high social costs, and “la pobreza ha vuelto a los niveles de antes.” Nevertheless, Mr. Macri reaffirmed his “pobreza cero” campaign promise, saying reducing poverty remained “lo que nos guía.” To compensate for the backsliding, he promised a 46 percent increase in the country’s cash transfer program for low-income families, the Asignación Univeral por Hijo.

Nevertheless, in discussing the economy, Mr. Macri seemed on the defensive. Recognizing that vulnerability, his speech pivoted to areas where his approval rating remains high: anti-corruption and crime. Argentina, he said, is “un estado que combate las mafias y previene la corrupción,” and he cited his recent executive order permitting government seizure of illegally obtained assets, “un reflejo de la clara postura que los argentinos tomamos” in fighting corruption. He also emphasized his tough-on-crime agenda, including efforts to reform the federal penal code.

Not surprisingly, given the political calendar, the opposition reacted negatively to the speech, arguing that it had deepened polarization. Agustín Rossi, leader of the leftist Frente para la Victoria bloc in congress and a former economy minister under Ms. Fernández de Kirchner, described Mr. Macri as “enojado e irascible.” For his part, Miguel Ángel Pichetto, the Senate president and a mainstream Peronist, called the speech a missed opportunity. “Se dejó pasar una nueva oportunidad de unir a los argentinos,” he said.

Throughout the president’s remarks, opposition lawmakers jeered and shouted insults. Mr. Macri dismissed the interruptions, saying, “los gritos, los insultos, no hablan de mí, hablan de ustedes,” but the lack of decorum highlighted the high tensions. As the former president of the Supreme Court, Ricardo Lorenzetti, said afterward, nowadays, the only way to draw attention to important issues in Argentina is “gritar, insultar, denunciar, disfrazarse o escandalizar.”

As for the public reaction, more than 60 percent of Argentines viewed the speech negatively, according to a Centro de Estudios de Opinión Pública survey. Yet despite the criticism, Mr. Macri appears optimistic. As in 2015, Cambiemos’s strategy is to persuade voters that Mr. Macri’s team remains Argentina’s best hope for resolving its chronic economic problems. He ended his state of the union with passionate calls of, “¡Vamos, Argentina!”

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Argentina Project

The Argentina Project is the premier institution for policy-relevant research on politics and economics in Argentina. Read more

Explore More in Weekly Asado

Browse Weekly Asado

Dengue Haunts South America’s Summers

Lessons from Costa Rica’s Economic Transformation

Women and Latin America’s Digital Revolution