The Taste of Chocolate: A Child of the Korean War Remembers

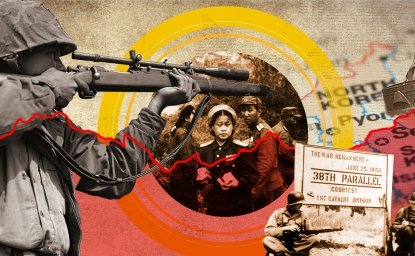

This blog post is part of the Korea Center's new collection − Stories Untold: Remembering the Korean War.

A blog of the Indo-Pacific Program

This blog post is part of the Korea Center's new collection − Stories Untold: Remembering the Korean War.

“GI, GI, give me chocolate, give me chocolate! GI, hello! Hello!”

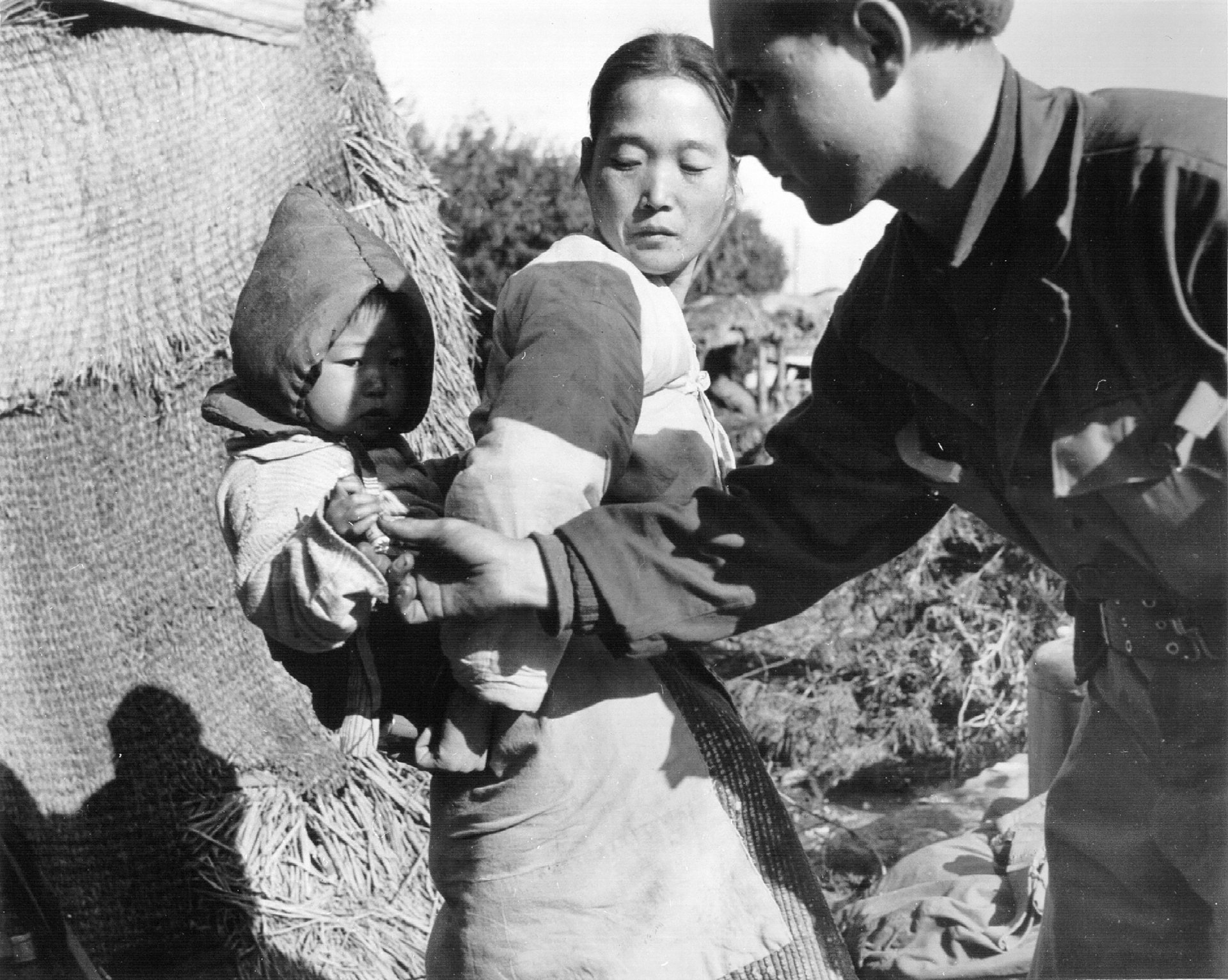

Maija Rhee Devine, in an interview with the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Oral History Program, recalls hearing South Korean children call out in broken English as they swarmed around American soldiers, hoping to get a taste of American chocolate. With the onset of the Korean War in 1950, these kinds of interactions had become commonplace.

Maija, also a young child at the time, stood with her mother and watched from afar as American soldiers took off their hats, filled them with chocolates and passed them around to the elated Korean children.

As Maija quietly observed the scene, one of the American soldiers gestured to her. Unfamiliar with the American hand signal, Maija stood still until the soldier approached her. With the calls of the other children behind him, the soldier squatted down and stuffed the pockets of Maija’s handknit sweater with chocolates as she stood silently, confused.

Maija later asked her mother why the American soldier had given her chocolates when there were so many other children who had been asking for chocolate. Her mother, also puzzled, speculated that perhaps it was because Maija’s green and red sweater reminded the soldier G.I. of Christmas back home in America.

Maija tasted the chocolate. In an instant, the echoes of the other children’s pleas to the soldiers made perfect sense.

Maija recalls cherishing the chocolates for as long as possible by limiting herself to tiny bites. She began to dream of going to America someday, where all those chocolates − and the kind soldier − had come from.

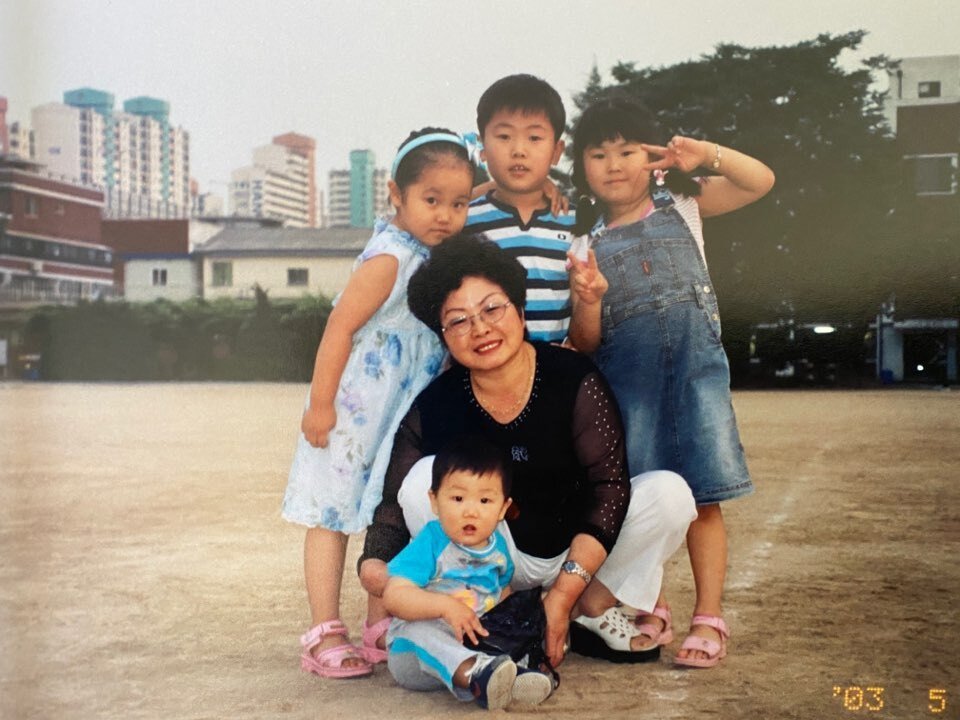

My own grandmother, Shin Jeong-pil, was only a toddler during the onset of the war and tells similar stories from her life in her southern hometown of Daegu. She, too, recalls sweet memories of American chocolate and the struggles of growing up in a war-torn environment.

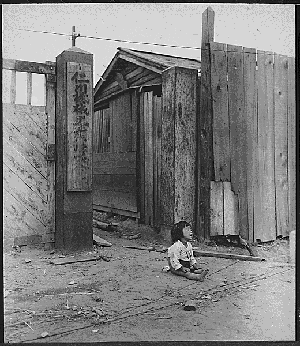

Like many Korean children in the 1950s, my grandmother, her four siblings and five cousins all became orphans when their fathers died in the war and their widowed mothers left their families to remarry.

The “Shin family orphans” were left in the care of my great-great-grandmother, who suddenly found herself having to operate an orphanage of sorts for her 10 grandchildren.

This was an overwhelming responsibility for my great-great grandmother. Although she did her best to attend to all 10 of her grandchildren, it was a difficult upbringing for her grandchildren; my grandmother has the physical scars to prove it.

With the attention of my great-great-grandmother stretched thin, my grandmother − a toddler at the time − managed to crawl up a window into the kitchen and toppled over into a boiling pot of water. Her head fell into a floating gourd atop the water, sparing her face, but her hands and arms were fully submerged, leaving her with severe burns.

Today, my grandmother is handicapped as a result of the incident, and her scars are a reminder of what the Korean War took from her: the care and oversight of her parents. My great-great grandmother saved my grandmother’s life by pulling her out of the boiling water in time, but neglect was an inevitable result of my grandmother’s circumstances, with no one to blame but the war that took the lives of over two million Korean civilians.

Hunger was also a problem. With no male figure in the family, it was very difficult for my great-great-grandmother to provide for the grandchildren.

Unfortunately, the Shin orphans were not the only hungry children in Daegu. My grandmother recalls that the streets were filled with war orphans living like beggars, without food to fill their stomachs and without shoes to cover their bare feet.

In the midst of these painful memories, however, my grandmother also remembers an occasional delight: treats from the American soldiers.

Whenever American soldiers drove by, the children would swarm towards them, yelling “Hello! Hello!” using the minimal English they knew to try to catch the soldiers’ attention. The soldiers would throw treats like chocolate, gum and candy to the children, and the children would scramble to grab a treat: finders keepers.

It was chaos. The stronger, older children would successfully grab more treats than the weaker, younger children. My grandmother, pointing to a scar on her forehead, said that small children like her often suffered injuries as they tried to keep up with the bigger children, scrambling for those delicious American treats.

Maija Rhee Devine married an American soldier and is now a proud citizen of the United States.

My own grandmother survived her hunger-filled childhood and now spends her time cooking for the homeless and hungry in her neighborhood in Seoul, South Korea.

Her scarred forehead, hands and arms, despite her insistence on hiding them under makeup and long-sleeve shirts, shine as a reminder of the difficulties my grandmother was able to overcome − both during and after the Korean War.

Sharon Lee is pursuing a B.A. in Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania, with minors in Legal Studies & History and Environmental Studies. She is a staff assistant intern at the Wilson Center’s Hyundai Motor-Korea Foundation Center for Korean History and Public Policy.

Follow the Korea Center on Twitter @Korea_Center or on Instagram at @wilsoncenterkorea.

The views expressed are the author's alone, and do not represent the views of the U.S. Government or the Wilson Center. Copyright 2020, Asia Program. All rights reserved.

The Center for Korean History and Public Policy was established in 2015 with the generous support of the Hyundai Motor Company and the Korea Foundation to provide a coherent, long-term platform for improving historical understanding of Korea and informing the public policy debate on the Korean peninsula in the United States and beyond. Read more

The Indo-Pacific Program promotes policy debate and intellectual discussions on US interests in the Asia-Pacific as well as political, economic, security, and social issues relating to the world’s most populous and economically dynamic region. Read more