The Uses of China

How Beijing helped keep Albanian Stalinism alive: Elidor Mehilli on why Albania veered away from the Soviet Union and toward the People's Republic of China.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

How Beijing helped keep Albanian Stalinism alive: Elidor Mehilli on why Albania veered away from the Soviet Union and toward the People's Republic of China.

How Beijing helped keep Albanian Stalinism alive

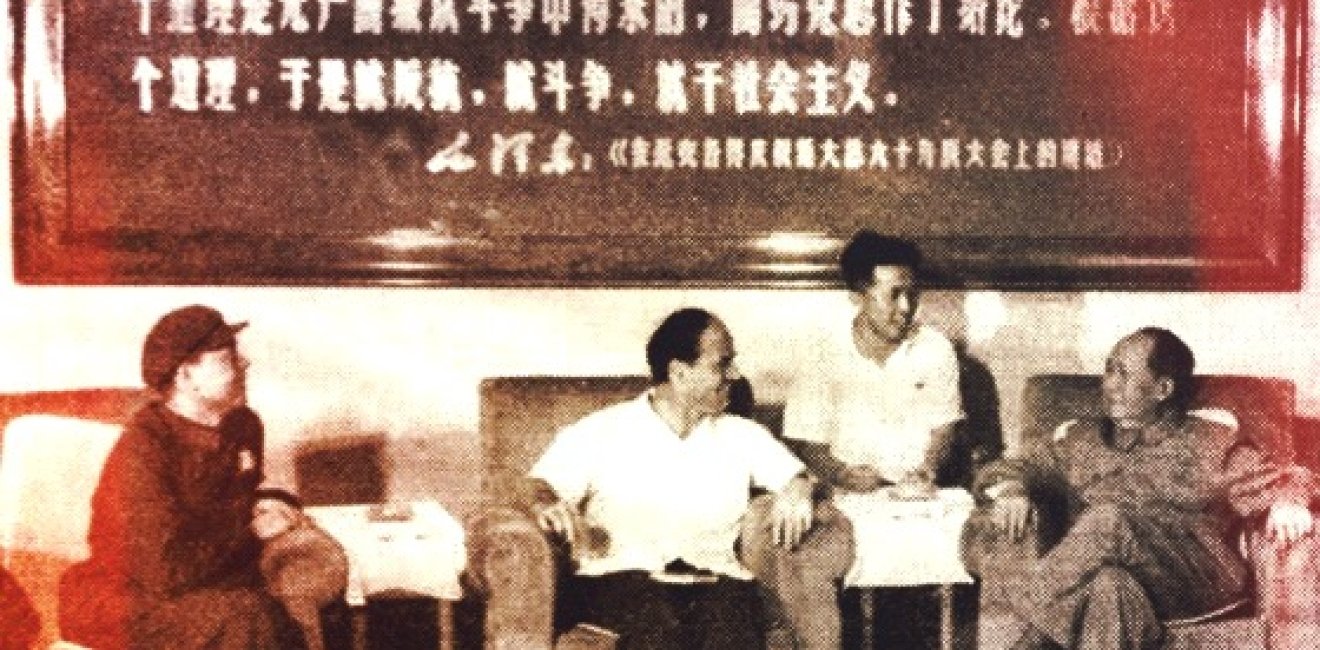

Comrade Mao: You have never fallen ill in your life?

Comrade Mehmet Shehu: We have fallen ill and we still do.

Comrade Hysni Kapo: One must always undergo cures.

Comrade Mao: One must always undergo cures against revisionism and Khrushchevism.

5 May 1966

Source: AQSH, F. 14/AP, M-PKK, V. 1966, Dos. 3, Fl. 7.

“If someone asks how large our population is,” Albanian Communist authorities were fond of declaring in the 1960s, “we say that it is 701 million.” Albania, which marked this week 105 years since the declaration of independence from the Ottoman Empire, was in fact a lot tinier than China’s hundreds of millions. And a great deal more insecure.

These were the years of Sino-Albanian friendship, inaugurated by an earlier dramatic split with a former powerful ally—the Soviet Union. From Stalin to Mao, out this month from Cornell University Press, tells the story of how socialism created a transnational traffic of people, ideas, and artifacts from the Mediterranean to East Asia.

Struggling to build an industrial basis for socialism, Albania was ruled by a relatively novice but militant Communist party. The cunning chief at the helm, Enver Hoxha, refused to fall in line with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s new course after Stalin. Hoxha paid lip service to calls for change, but rejected substantial reform, seeing in Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization a formula for self-destruction.

There could be no coexistence with capitalism, he insisted after relations with the Kremlin turned icy in 1960. (Hoxha continued to heap praise on Stalin, whom he credited with saving Albania from Yugoslav annexation in the 1940s, even as his Chinese partners periodically took jabs at the vozhd.)

In the 1950s, Albania forcefully championed the Soviet Union as a civilizational model, growing economically dependent on Moscow. The anti-Soviet turn provoked confusion at the lower ranks. And no matter how effusive the talk about the new eternal Sino-Albanian bond—the Soviet bond had been eternal too, until it had monumentally collapsed and died—the distance to China was immense.

High-level delegations came and went, delivering fiery speeches, declarations of admiration free-flowing from Vlorë to Shanghai. Underneath it all, however, the partnership was uneasy, and it still remains misunderstood.

China seemed to offer some advantages, or at least such were the assumptions made in Tirana. After Soviet specialists left Albania, officials turned to Beijing for credits and technical agreements, devising ever-longer wish lists: grain, complete factories, oil refineries, installations, advisers. The requests proved onerous, and Beijing occasionally complained. Nevertheless, Chinese officials issued substantial aid. (Exact figures are still hard to reconcile; both sides declared vastly different figures and many agreements were ad hoc.) Albania’s government also eventually came to rely on Beijing for weapons and ammunition, building a foundation for the later militarization of daily life in the 1970s.

But this was only part of the story. For a peripheral European country, China could also serve as a giant amplifier for speaking to revolutionaries across the world.

In the mid-1960s, the party devised a special hard currency fund (in large part with Chinese money) to assist Marxist-Leninist groups abroad, including in capitalist Western Europe and in “the revisionist East.” In 1964, the Secretariat agreed to send small sums to sympathetic groups in Italy, Poland, Belgium, Portugal, Brazil, Peru, and Colombia. The Iranian Revolutionary Organization of the Tudeh Party held its first congress in Tirana in 1965.

The Soviets had promised to integrate rural and needy Albania into a new world order. The Party of Labor ended up pursuing integration into an alternative socialist order defined, in part, by resistance to Soviet pressure. Whereas the establishment had once felt unmistakably inferior vis-à-vis the homeland of Lenin, it now felt emboldened by the Sino-Soviet split.

At times, in fact, as From Stalin to Mao shows, Hoxha lashed out at the Chinese for wavering ideologically, though disagreements were kept private. And so the regime, unreformed, evoked various degrees of sympathy among anti-Soviet groups abroad—observers captivated by the spectacle of a small country taking on a giant.

Yet China also served as a counter-example. Erroneously, observers have long assumed (and some still continue to claim) that Albania mindlessly copied Mao’s Cultural Revolution in the 1960s. This sees the Balkan country as a perennial client state, completely missing the underlying dynamic created by conflict under the banner of a guiding ideology.

It is true that Hoxha, after initial panic, eventually praised Mao’s gamble, embracing the Red Guards in Tirana and hailing the Chairman as an inspiring thinker. (Then ridiculing him in his so-called memoirs, which have served as sources in the secondary literature.) In reality, the Cultural Revolution was read as a warning. Despite formal parallels, revolutionary warfare was not allowed to engulf the party apparatus in Albania, as it did in China.

Writing the history of these Cold War zigzags, I have found it necessary to combine archival materials from the foreign section of the Central Committee, with Politburo protocols, where anxieties over China, for example, occasionally surface more openly.

But crucial as party archives are, the rubric of friendship was bigger than the party apparatus. Transnational contacts also produced personal histories of discovery, challenges of translation, episodes of misunderstanding, emotional bonds, along with disappointment and resentment. Encouraging contacts on a cross-continental scale, socialism generated feelings of familiarity while sharpening differences.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more