A blog of the Kennan Institute

BY MAXIM TRUDOLYUBOV

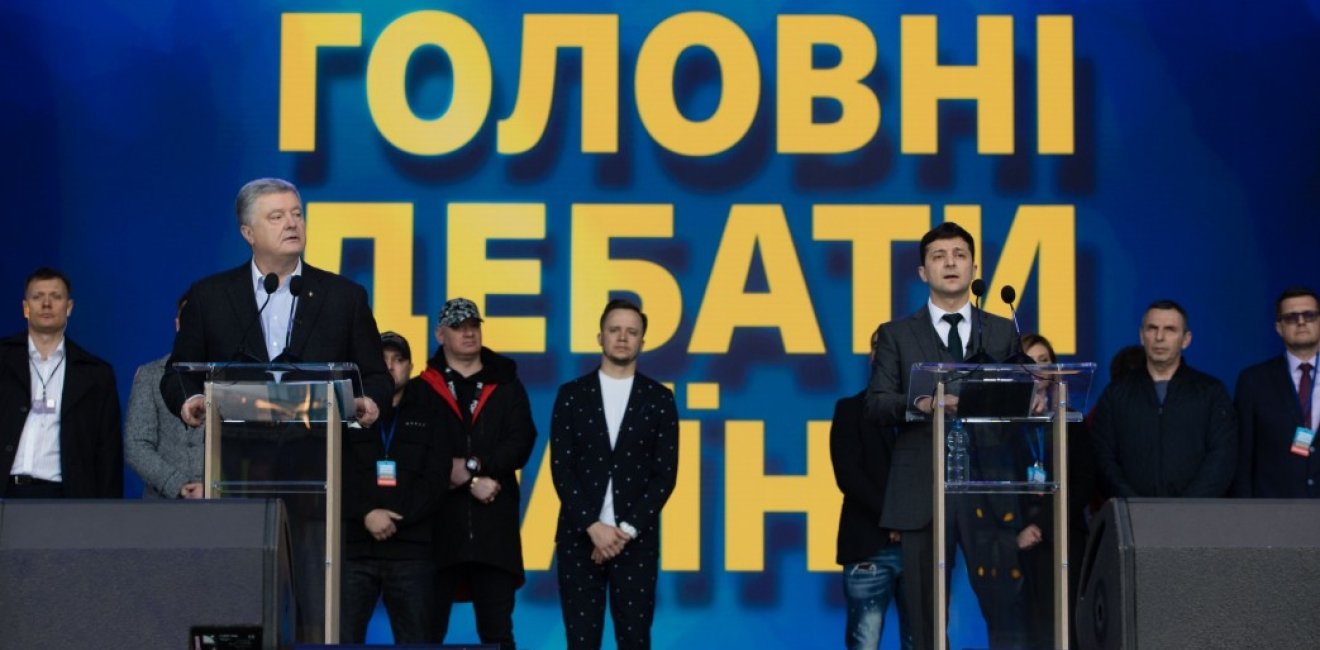

Even as the Kremlin seems to be taking a wait-and-see approach toward Ukraine’s president-elect, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, Russia’s independent observers and intellectuals are reflecting on Ukraine’s choice and Russia’s politics.

“We will make our judgment based on specific actions,” noted Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov, adding that it was too early to send congratulations to Zelenskiy or to talk about cooperating with him. The election’s legitimacy was put into question when 3 million Ukrainians living in Russia were denied the right to cast their ballots in Russia, Peskov said. Ukrainian authorities said earlier this year they could not hold “an election on the territory of the aggressor state.”

As opposed to that official view, interest in electoral developments in Ukraine among Russia’s independent public sphere was genuine and serious. When the news came of Zelenskiy winning and Petro Poroshenko conceding defeat, those posting to social media or commenting on other media not controlled by the state seemed to be searching for answers on both Ukraine and Russia.

Many independent commentators in Russia saw the very fact of power peacefully changing hands as the result of an election as a major achievement—and congratulated Ukrainians on itt. Others pointed out that a generational change was of utmost importance. Russian independent commentators’ reactions to the events in Kyiv were once again, just as in 2004 and 2014, a reflection of sorts of their analysis of Russia’s situation.

Boris Akunin, the author of popular detective fiction, who has lived outside Russia for a few years but has hundreds of thousands of followers on Russian-language social media, wrote in Russian on Facebook, “I would like to congratulate all Ukrainian readers of my blog on the fact that you have a working democracy in your country and on the fact that power [in your country] can change hands via an election. I do not know what to expect from the new president, but I do sincerely wish that the changes in your life might be for the better.”

(All of the quotations in this blog were originally in Russian and intended for the Russian-speaking audience.)

“Fair elections, competitive debates, a dignified concession, transfer of power—all these things, frankly, are causes for envy and respect,” said Leonid Volkov, chief campaign manager for Alexei Navalny and his Anti-Corruption Foundation. “It will be hard for Zelenskiy, including because of high expectations, but I sincerely wish much luck to him and to Ukraine.”

“I did not have a preference among the two candidates, but I must note that this was an election that saw a challenger defeat a sitting president, and this election will actually lead to a transfer of power,” Ivan Kurilla, professor of history at the European University at St. Petersburg, wrote on his Facebook page. “This is the main if not the only real attribute of a democracy.… And this is not the first time [it has happened in Ukraine]. Even those who refuse to accept the Maidan uprisings [of 2004 and 2014] as clean cases of democratic change cannot fail to see that Yanukovych defeated Yushchenko. This fact is more important than the specific names of the winners. I remind you that nothing of the kind has EVER happened in Russia. But I still harbor hopes for it happening in my lifetime,” he wrote.

“Russian society’s problem is in its dead seriousness, in its sense of a fate and mission, in its tendency to compare itself to its great forefathers, in its urge to prove something to others and themselves,” wrote Alexei Makarkin, vice-president at the Center for Political Technologies in Moscow. “I have a persistent feeling that Russian society wants to live differently but is embarrassed to admit it. Ukrainian society is trying to live differently, without this strain, without this perennial triad of ‘the nation, the army, the church.’ Whether it will succeed in this adventure, I do not know, but thank you for trying.”

“To receive more than 70 percent of the vote, Vladimir Putin had to take over the presidency as [Yeltsin’s] designated successor, to work for two terms as president, to preside over a period of a long economic growth, then return to power, mobilize everyone for a fight with the domestic and external enemy, annex Crimea, preside over the period of ‘stability.’… But there seems to be an easier path to getting one’s 70 percent of the ballot,” wrote Alexander Baunov, editor-in-chief of the Carnegie Moscow Center’s website. “Note to the Russian political class: opening up the country’s political system is not such a scary proposition; your 70 percent will find you even if you are in opposition.”

“The fact that Zelenskiy was listening to [the American rapper songwriter] Eminem on the morning of election day is super important: nowhere in the post-Soviet space has there been a ruling politician from a new generation,” wrote Pyotr Verzilov, the Russian activist artist, who used to be married to Pussy Riot member Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and was an unofficial spokesperson for the group. “Name one post-Soviet leader who would listen to an Eminem record on an election day,” continued Verzilov, who thinks Eminem might be seen as a generational boundary of sorts.

“I could not quite understand why, a year and a half ago, Petro Poroshenko was so keen on getting rid of Mikheil Saakashvili,” wrote Konstantin Sonin, professor at the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy and Moscow’s Higher School of Economics, before second round results were announced. (Saakashvili was president of Georgia from 2004 to 2013 and governor of Ukraine's Odessa Oblast in 2015 to 2016. After a conflict with the Ukrainian authorities, he was deported from Ukraine and his Ukrainian citizenship was suspended.) “If it is true that the Ukrainians hate their political class that much—and I can only read the results of the first round as ‘get out of here, you all’—then Saakashvili had a chance in the 2019 presidential elections.” Both Saakashvili and Zelenskiy are outsiders, each in his own way, Sonin maintains, concluding, “A former Georgian president as president of Ukraine would be strange, but no stranger than Zelenskiy.”

“I see [Zelenskiy’s win] as a positive sign, as I generally see the populist wave positively. But I would like to correct all those journalists and bloggers who call Zelenskiy a novice and a weak politician. The series he starred in launched in 2015… Even then, in 2015, Zelenskiy, Kolomoysky (a Ukrainian businessman and the former governor of Dnipropetrovsk oblast, who is thought to back Zelenskiy), and probably some other people had met to consider Zelenskiy’s presidency,” wrote Artemy Magun, professor of democratic theory in the Department of Sociology and Philosophy at the European University at St. Petersburg. “This kind of long-term thinking is a sign of high political and media professionalism.… It was clear even 20 years ago that media experts were coming to replace traditional professionals in politics in liberal democracies. Trump and Zelenskiy are only the beginning.”

But the Kremlin is unlikely to be as partial to Zelenskiy as it is to Trump. “For the Kremlin, this election, the very fact of a free election, is as traumatic as the Maidan was. That is why I would expect an outpouring of rage, not enthusiasm for shaking hands [with Zelenskiy]. The 'Ukrainian factor' has caused a lot of bad things that happened to the Putin regime,” said Alexander Morozov, co-director of the Boris Nemtsov Russian Studies Center at Charles University in Prague. “The second Maidan led to the annexation of Crimea and to a pivot to geopolitics. Thus how the free election proceeded will likely provoke some active measures on Russia’s perimeter—namely, a ramping up of the fight for Belarus.”

Author

Editor-at-Large, Meduza

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in The Russia File

Browse The Russia File

Chechnya as a Model of Modern Russia

Russia’s Indigenous Communities and the War in Ukraine

Gas and Power in a Changing US–Russia Relationship