A blog of the Indo-Pacific Program

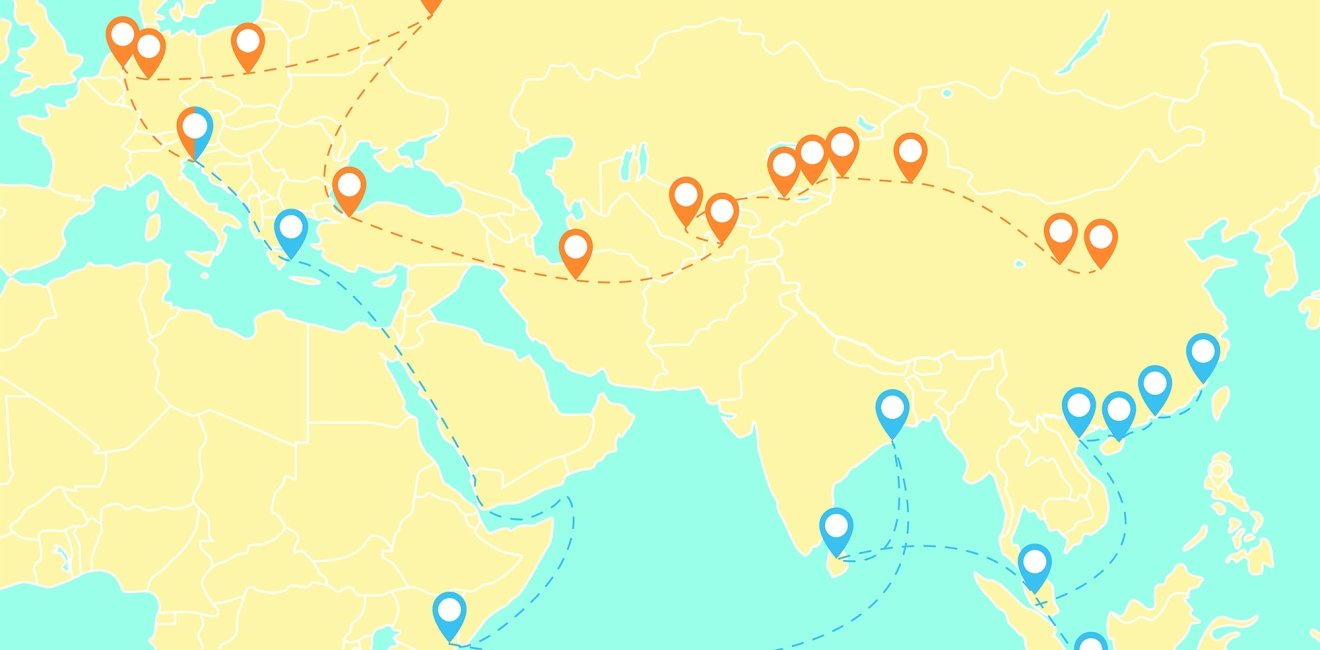

In any conversation about the Belt and Road Initiative (or BRI, China’s huge transport corridor project) and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (or CPEC, the Pakistan component of BRI) and the prospects for expanding it to Afghanistan, there is a risk of putting the cart before the horse.

There’s so much that needs to happen before we can talk about this prospect. Several things specifically must be in place, which I’ll list in ascending order of difficulty.

First, there will need to be buy-in from the Taliban. The Taliban has signed off on some major infrastructure projects, including the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline project. The Taliban has said it supports the project as a key component of Afghan economic infrastructure. Now, if the Taliban supports TAPI, one would think it could come around to BRI or CPEC, which is not an Afghan government project enterprise, but rather projects of the Chinese and Pakistani governments—neither of which have ever been enemies of the Taliban.

Second, and more challenging, is that in order to have BRI and CPEC in Afghanistan, you would need to have more trust between Pakistan and Afghanistan. This is a relationship that blows hot and cold; there are good times and bad times. To their credit, both Kabul and Islamabad have sought in recent years to strengthen their relationship. Still, there’s a lot of deeply embedded mistrust, much of it attributable to lingering resentment about cross-border terrorism and a longstanding border dispute.

You will likely need a peace deal in Afghanistan, or at least more stability, to talk seriously about major Chinese infrastructure development there.

Third, most importantly, and the most difficult to achieve, is that you will likely need a peace deal in Afghanistan, or at least more stability, to talk seriously about major Chinese infrastructure development there. China has had to put most of its investment plans in Afghanistan on hold, BRI related or other, due to the war. Beijing is not afraid to navigate difficult security environments in its infrastructure investments abroad. We see this through its investments in parts of Africa and Southeast Asia. Still, it can only do so much in a warzone. We all know the challenges of the fledgling peace process. And even if there is a peace deal, there would be lingering terror threats from the various other militant organizations in Afghanistan, like ISIS, that wouldn’t be party to a peace process and have no fondness for the Chinese or Pakistani governments.

At any rate, what can one say about the impact of BRI and CPEC on the U.S. Afghan strategy?

I’d argue that there’s not much of an impact on U.S. Afghan strategy. There’s a misconception among some observers, many of whom are in Pakistan, that America is present in Afghanistan to push back against China, or even to contain China, and by extension to push back against a potential CPEC or BRI expansion into Afghanistan. That’s not true. The United States is not in Afghanistan to push back against China. It’s there to push back against terrorists. It looks at Afghanistan mainly through a counterterrorism lens.

If you get a President Joe Biden in the White House in January...we can safely assume it will look at China as a strategic competitor, and threat, in the same way as Trump.

It is certainly true that U.S.-China policy is very much focused on pushing back against China—that is the essence of the U.S. Indo Pacific strategy, even if U.S. officials don’t state that explicitly. The United States in recent months has started to articulate public opposition to CPEC—we all remember the famous, some would say infamous, speech that Amb. Alice Wells made at the Wilson Center last year when she delivered a scathing critique of CPEC. This marked an evolution in U.S. policy, as up until Wells’ speech, U.S. criticism of CPEC had been relatively muted, and there had not been any official public rejection of CPEC. CPEC, and Pakistan, have sadly got caught up in a worsening U.S.-China rivalry. Wells’ speech was not meant to be critical of Pakistan—far from it; the second part of her speech, which is not cited nearly as much as the first part when she criticizes CPEC, called for stepped up U.S. investment in Pakistan. The speech was meant to be critical of the Chinese government and its investment models. So, yes, the U.S. government is intent on pushing back against China. And this is a bipartisan goal. If you get a President Joe Biden in the White House in January, his administration may not resort to the witheringly sharp rhetoric against China that you hear from the Trump administration, but we can safely assume it will look at China as a strategic competitor, and threat, in the same way as Trump.

At any rate, U.S. policy is focused on pushing back against China only in places where China is present and has a deep footprint. And it doesn’t really have a deep footprint in Afghanistan. It’s not very present there, because the war makes it hard to develop a deeper footprint. So, to be very blunt, the U.S. Afghanistan strategy is not impacted by, guided by, or informed by CPEC or BRI. It is informed by other things, like terrorism. And pursuing peace talks. And planning for its exit.

So I think the better question to ask is the reverse of the one posed initially. And that is, what is the impact of U.S. Afghan strategy on CPEC and BRI?

But that first requires an examination of the U.S. Afghan strategy itself. What is this strategy? I’d actually argue that since the very first few weeks of the war, when U.S. forces achieved their core goals of knocking out al-Qaeda sanctuaries and removing the Taliban from power, there hasn’t been a terribly coherent U.S. Afghan strategy. And this is one of the many reasons why the U.S. mission in Afghanistan has been such a mess. The questions of why are we there and what are we fighting for have never really been adequately answered for nearly two decades. Be that as it may, today, the answer basically revolves around three goals: working with Kabul, Islamabad, the Taliban and other players to help facilitate an Afghan peace process that ends the war; preparing for a smooth withdrawal of military forces; and figuring out how to maintain some type of a counterterrorism capacity in Afghanistan. And I should say this is a bipartisan strategy. This is what we should expect to see in the coming months regardless of whether Trump stays in the White House or is replaced by Biden.

These U.S. goals, if achieved, and that’s a big “if,” can deliver major boosts to BRI. And that’s because if you get a Taliban peace deal and reduce terror, then that bodes well for China’s ability to start building out BRI. So, ironically, current U.S. Afghan strategy could give a considerable fillip to America’s top strategic rival: It could give China more stable space to operate in, and in due course to expand its Belt and Road Initiative—a project that the United States is trying to push back against, futilely, through the Indo-Pacific strategy and related measures.

Another question that’s worth asking is what does the future U.S. Afghan strategy mean for CPEC and BRI? It’s hard to answer this question; we don’t know what that strategy will look like. But let’s game this out a bit. If the United States draws down its military presence nearly to zero by the spring of next year, per the terms of the U.S.-Taliban agreement, and there is not a peace deal in place by that time, and the war continues, then I doubt we will see much forward movement on a CPEC expansion, as the security situation would make it very difficult. And even if the U.S. military withdrawal is slowed down, amid the Taliban’s failure to uphold its commitments in the deal with the United States, and the peace process is not successful, then I doubt there would be much forward movement with CPEC expansion.

That said, even with Afghanistan still at war, there can be opportunities to lay the foundation for CPEC and BRI in Afghanistan when the country is more stable or at peace. Scaled-up Afghanistan-Pakistan trade would be a major step forward—a confidence-building measure leading to better bilateral relations, and also a means of building momentum for deeper economic cooperation, including infrastructure.

What would make matters worse for the United States is that other states that are both regional actors and U.S. rivals would be poised to step up their own role to contribute to or build out infrastructure projects—countries like Russia and Iran.

Now, if the U.S. military withdrawal takes place, and there is a peace deal, or even some type of ceasefire or violence reduction plan, then that could enable space for an expansion of CPEC into Afghanistan. This is not something that would be a good thing for U.S. interests, given that U.S. policy, at least for now, tends to take a zero sum view of its deepening rivalry with China, and it wouldn’t want China to be stepping up its role in Afghanistan. What would make matters worse for the United States is that other states that are both regional actors and U.S. rivals would be poised to step up their own role to contribute to or build out infrastructure projects—countries like Russia and Iran.

In an ideal world, that would be a major opportunity for the United States, for Pakistan, for China, for Afghanistan, and the whole region. If U.S. troops leave Afghanistan and there is some semblance of peace in Afghanistan, Washington would have the opportunity to operationalize a long-aspirational U.S. government vision for a new U.S.-led effort to make Afghanistan and Central Asia more integrated and more prosperous—this is an initiative known as the New Silk Road Initiative. This could entail ramping up efforts to complete TAPI, CASA 1000, and other U.S.-backed infrastructure projects, and to link them up with BRI projects in Afghanistan and the broader region. And at the end of the day, these are the types of outcomes the United States supports in Afghanistan and the broader region: more connectivity, more trade, more prosperity, and more stability.

I say this is the ideal scenario because it is also a highly unlikely scenario. This would require peace in Afghanistan. And it would also require the United States and China to set aside their bitter rivalry in order to work together on shared goals of infrastructure development.

Given the strength of the U.S.-China rivalry—one that will remain in place no matter who wins the U.S. election in November—one needs to keep expectations low that there could potentially be cooperation between the United States and China in Afghanistan.

Ultimately, Washington’s ability to implement its longstanding vision of more connectivity and prosperity in Afghanistan and Central Asia (originally articulated in its New Silk Road Initiative) will depend on two key factors: A capacity to field an on-the-ground civilian presence in the absence of a security umbrella previously provided by U.S. troops, and successful diplomatic efforts that improve relations with bitter rivals. Both are rather unlikely outcomes.

The most likely outcome of a U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, if there is a peace deal, is that it will essentially cede ample ground to its top rivals in Afghanistan—China but also Russia and Iran. This means that Washington could find itself locked out of the very regional cooperation that it very much wants to see take shape in Afghanistan. This should not necessarily be seen as a bad thing for U.S. interests, given that these countries—through shared infrastructure development—could create the very outcomes supported by the United States. But the fact that the countries involved would happen to be the United States’ most bitter rivals would make it difficult for U.S. officials to say their interests are being served, as its top rivals would be embedding their influence in a strategic space where the United States is no longer present.

Note: An earlier version of this paper was delivered as a speech at a webinar organized by the Islamabad Policy Research Institute on September 15, 2020.

Follow Michael Kugelman, deputy director of the Asia Program and senior associate for South Asia, on Twitter @MichaelKugelman.

The views expressed are the author's alone, and do not represent the views of the U.S. Government or the Wilson Center. Copyright 2020, Asia Program. All rights reserved.

Author

Indo-Pacific Program

The Indo-Pacific Program promotes policy debate and intellectual discussions on US interests in the Asia-Pacific as well as political, economic, security, and social issues relating to the world’s most populous and economically dynamic region. Read more