A blog of the Kennan Institute

No end to the hostilities in Ukraine is in sight. The situation on the front line may change many times over before a peace is achieved. Yet, some fundamental outlines of the postwar world arrangement can be discerned even in the fog and darkness of this war.

Ukraine has a peace plan and a vision of a postwar world. For this vision to be fulfilled, the world will need a pacified and compliant Russia. One major postwar question is whether Russia could be expected to behave in a reliable and civilized manner so that the wounds of war could start to heal and a peace could start to take hold.

War is violence, chaos, and uncertainty. But even today, we can talk about several points of certainty. The first of them is that Putin’s Russia has failed to reach its maximalist goals in Ukraine. Ukraine has defended its statehood, identity, and agency in international relations.

The second certainty is that the positions of Ukrainian politicians supported by society regarding the end of the war have been put forward. There is a Ukraine peace formula and Ukrainian ideas about the postwar security order ("Sustainable Peace Manifesto"). It is these positions, and not Russian, Chinese, Indonesian, or South African ones, that will be the point of departure for any future peace negotiations.

The third certainty is that the Russian regime and a significant part of Russian society, but not the entire society, have tied themselves to this war.

The fair and understandable demands of the Ukrainian side include war reparations, disarmament, and even the denuclearization of Russia, as well as the restructuring of Russia’s political regime, and the indictment and punishment of those responsible for launching the war of aggression and committing war crimes.

Call for an External Coercion Mechanism

Not only a Russian postwar regime but also a significant portion of Russian society will resist some of Ukraine’s demands. The authors of the Ukrainian manifesto acknowledge this: “The Russians themselves are incapable of carrying out these transformations.... Russia itself cannot break free from the vicious circle of its past.”

This means that for a sustainable peace to be established, as envisioned by representatives of Ukraine, not only does Russia need to be defeated, it needs to be governed by an external authority. The desired vision of a postwar world implies the existence of an effective mechanism that would enforce Russia’s compliance with a long list of conditions.

A provisional administration set up by occupying powers could provide such enforcement, but the feasibility of occupying Russia and forcefully changing the Kremlin regime falls into the realm of high improbability. Such a development cannot be ruled out completely, but it is difficult to think about it as a reliable condition for implementing the Ukrainian plan for post-war order.

Call for a Stronger UN

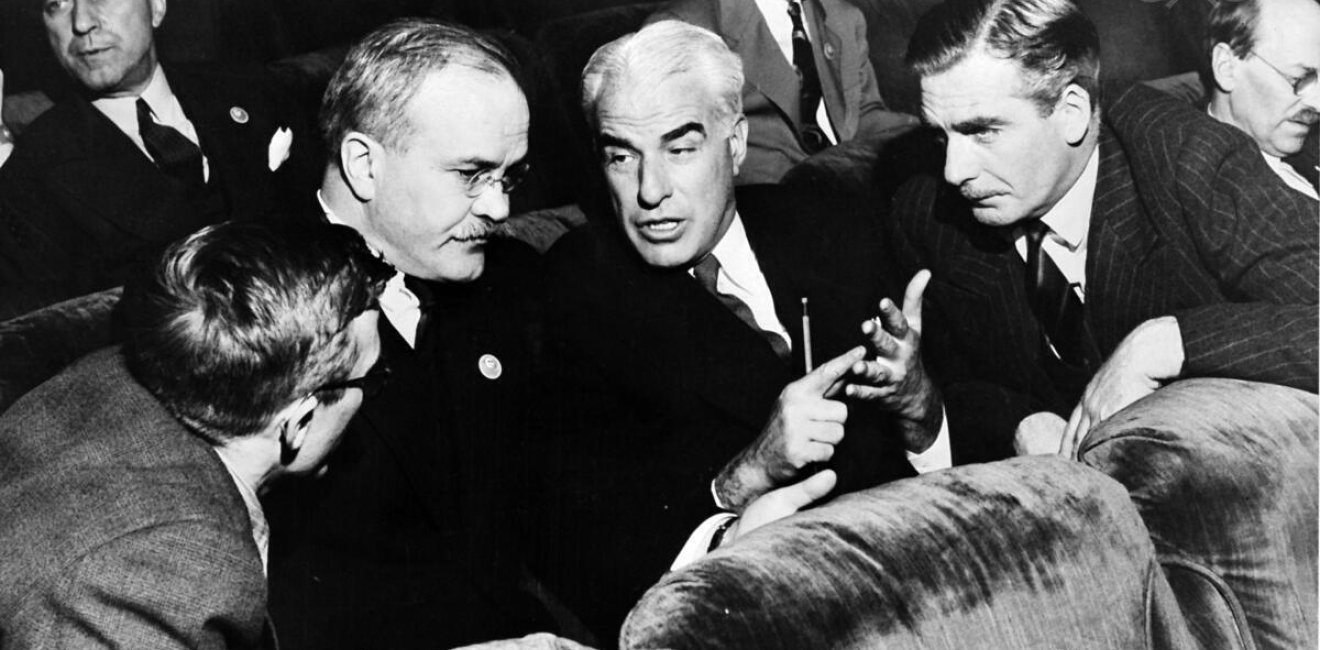

A more feasible mechanism appears to be trying to exert influence on Russia through international organizations. The key organization capable of influencing Russia should have been the UN, but the limited powers of the UN are a feature embedded in its design by its founding states. The superpowers of the 1940s, primarily the United States and the Soviet Union, while agreeing on the need for an international organization to exist, mistrusted each other and did not want the global structure they created to be used to exert pressure one on the other.

The crucial feature of the UN, significant in this case, is the lack of an enforcement mechanism, meaning there is no way to compel the implementation of International Court of Justice decisions and General Assembly resolutions. The UN has no police force or permanent military forces of its own.

In this case, the extremely narrow composition of the permanent members of the UN Security Council and the veto power each wields are also significant factors. In its current form, the UN Security Council, owing to Russian and possibly Chinese veto power, would block any decisions aimed at compelling Russia to take any actions.

Russia inherited its permanent membership in the UN and on the UN Security Council from the USSR and acquired its position in these structures without the UN voting on accepting a new member into the organization. Yet, the withdrawal of Russia from the Security Council, as the Ukrainian manifesto suggests, is difficult because there is no mechanism to remove a permanent member of the Security Council.

Even if Russia were miraculously excluded from the UN Security Council, China would still keep its seat, which means that a reform of the UN must run deeper. For Ukraine’s sustainable peace to work, it will need a Security Council with a broader composition and a UN with an enforcement mechanism. These ideas do sound implausible now but, given political will, they can be realized. Such restructuring of the UN would require the determination of key world powers, comparable to the determination of the participants in the anti-Hitler coalition that created the current UN in 1945.

Call for a Stronger Coalition

That coalition included all the major powers of the mid-twentieth century. The current anti-Putin coalition is highly representative, but it lacks China and many non-Western powers whose voices would be necessary for a UN reform.

But even if we imagine for a second that Brazil, India, China, South Africa, and other major non-Western powers joined the anti-Putin coalition and it became as broad as possible, it is still unclear whether the world powers would agree to the creation of a stronger UN.

The United States and China would most likely oppose such a move. Both the United States and China rarely sign international agreements that imply any external interference in their internal affairs, and by agreeing to the creation of an international enforcement mechanism, they would have to accept at least the possibility of such an intervention.

Call for a Stronger Russian Society

All of this means that achieving a sustainable peace according to Ukraine’s plan solely through the external coercion of Russia, even a defeated Russia, to fulfill a long list of demands is unlikely. There is no functioning mechanism of compellence. Moreover, actions taken through coercion provoke resistance and do not lead to sustainable behavioral change at either the individual or the national level. This, in turn, means that for reparations to be paid, for criminals to be punished, and for Russia to cease posing a threat to Ukraine and the world as a whole, Russian society must be included in the process of restructuring the world after the current war.

The authors of the “Sustainable Peace Manifesto” address not only Ukrainian society and the international community but also Russian civil society and the country’s opposition forces. This is a crucial caveat: it leaves room for Russia to voluntarily accept political commitments and changes that are favorable to Ukraine and peace.

It is necessary to ensure that an exit from the war and recognition of defeat become a conscious choice for a significant part of Russian society. The first step toward this state is the success of the Ukrainian armed forces and the creation of the most favorable situation on the ground for Ukraine. If an obvious defeat on the battlefield is not inflicted, the Russian regime will strive for any intermediate solution (“neither peace nor war”) because it has not achieved victory and cannot afford defeat.

The second step would be for Russian society to realize all the possibilities for development and trade that were lost as the result of the actions of a group of deluded Kremlin politicians. Western countries, particularly the EU, could make it clear to Russian society and opposition politicians that acknowledging responsibility for the war, paying reparations, holding the guilty accountable, installing democratic reforms, and creating a system of accountability to society would help Russia gradually regain some trust with Western societies. It would allow Russia to return to Western markets, reconnect to the international education system, and rejoin the West’s cultural scene.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.

Author

Editor-at-Large, Meduza

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in The Russia File

Browse The Russia File

Chechnya as a Model of Modern Russia

Russia’s Indigenous Communities and the War in Ukraine

Gas and Power in a Changing US–Russia Relationship