The Origins of North Korea-Vietnam Solidarity: The Vietnam War and the DPRK

Click here to download this paper as a PDF.

NKIDP Working Paper #7

The Origins of North Korea-Vietnam Solidarity: The Vietnam War and the DPRK

Benjamin R. Young

February 2019

During the 1960s, the Vietnam War captured the international spotlight. Despite Pyongyang’s geographic distance from this conflict, North Korea’s founding leader Kim Il Sung felt a special connection to the Vietnamese struggle and often voiced his support for the Vietnamese communists.

The Vietnam War allowed Kim Il Sung to improve his international reputation as a man of direct action and militant vigor. By directly assisting the Vietnamese struggle, Kim enhanced his credentials as a world revolutionary leader uninhibited by the petty divisions of the Sino-Soviet split. Kim also used the Vietnam War for domestic reasons as a way to politically mobilize citizens at home and create certain favorable domestic environments for the regime. He presented the image of an embattled Vietnam as an increasingly likely future for the citizens of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) if they did not rally around the leadership in Pyongyang and send military forces to stop US aggression in Southeast Asia. To borrow historian Toni Weis’ phrasing, the DPRK government’s solidarity with Vietnam became a means for North Koreans to affirm their support for the political system.[1] Finally, Kim also saw the war in Vietnam as a mirror image of the Korean situation and pragmatically used the conflict to gain intelligence on the South Korean military and test his pilots in wartime combat for a future conflict on Korean soil.

Despite intense scholarly interest in the Vietnam War and North Korea’s militancy, scholars have insufficiently researched Pyongyang’s Vietnam War solidarity campaign. Although many scholars have tried to tie North Korea’s 1968 seizure of the USS Pueblo to the Vietnam War, few have explored the vast network of ties established between the Korean Workers’ Party and the Vietnamese communists prior to this incident or the intense mobilization campaign undertaken domestically in the DPRK by Kim Il Sung’s regime.[2] Using North Korean state-run media, multinational archival documents, and secondary sources, this Working Paper investigates the North Korean regime’s use of the Vietnam War as a tool for mass mobilization that in turn strengthened the Kim family’s grip on domestic power.

***

Despite domestic political and economic struggles after the Korean War, Kim Il Sung remained dedicated to aiding the international revolutionary movement. When Soviet ambassador to the DPRK A.M. Puzanov met with Kim on 1 August, 1957, he told the North Korean leader that Moscow had agreed to provide North Vietnam with one billion rubles for flood aid. Not wanting to be outdone by Moscow, Kim announced that the DPRK would also provide flood assistance to Hanoi. Although North Korea’s amount of aid—5,000 rubles—paled in comparison to the large Soviet aid package, Kim showed that even during times of economic difficulty his government would assist allies, especially guerilla fighters, during their times of need. Kim Il Sung told the Soviet ambassador “that the population of North Vietnam needed to be helped.”[3] Kim remained dedicated to helping the Vietnamese communists after 1957 and later offered North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh military assistance during the Vietnam War. However, Kim Il Sung’s Vietnam War policy was not purely motivated by grand notions of international revolution. The Vietnam War proved useful in mobilizing the North Korean people, distracting them from domestic problems, and consolidating Kim Il Sung’s absolute authority within the DPRK’s political system.

From 28 November to 2 December, 1958, Kim Il Sung visited North Vietnam after a short trip to China. Ho Chi Minh welcomed Kim Il Sung to Hanoi on a very warm day and purportedly said, “We give you the heat of our country as a gift because brotherly friendship is always warm.” At a mass rally in Hanoi, Kim ended his speech by saying a few phrases in Vietnamese: “Long live the unification of Vietnam! Long live the unification of Korea! Long live socialism! Long live world peace!” The seemingly impressed Vietnamese crowd “responded at the top of their voices.” During his trip to North Vietnam, Kim visited the Namdinh textile factory, an agricultural co-op on the outskirts of Hanoi, and the Vietnamese Military Officers’ School.[4] Kim’s visit to North Vietnam proved valuable for fostering close ties between the two nascent communist states.

On 27 March, 1965, the front page of the Rodong Sinmun featured the headline, “The Korean people will provide any kind of support, including weapons, to the Vietnamese comrades and upon request will send volunteer forces.” This headline was labeled as a “government statement.”[5] This was the first time that Kim Il Sung explicitly offered military support to a foreign leader and it began a month-long cycle of articles in the Rodong Sinmun recruiting volunteers for the Vietnam War. This little known episode of North Korean internationalism proved important for Kim’s domestic and foreign policies. On one hand, Kim used the Vietnam War and the threat of a US invasion as a way to mobilize his countrymen. The recruitment efforts for Vietnam War “volunteers” were reminiscent of the Chinese volunteers for the Korean War. Just as Mao used the Korean War to push his strategy of “continuous revolution,” Kim Il Sung used the Vietnam War in a similar vein.[6] On the other hand, Kim demonstrated his commitment to world revolution by visibly offering Ho Chi Minh his military services. Ho covertly agreed to allow the North Korean air force to fight in the war, albeit disguised as Vietnamese aircraft.[7] Thus, the Vietnam War reflects the intersection between the domestic and foreign policies of Kim Il Sung’s regime.

Pyongyang used the Vietnam War as a way to reaffirm the North Korean peoples’ support for socialist internationalism. In April 1965, the North Korean press featured a barrage of letters from mass organizations, such as the Korean Unified Farm Workers’ Association, to the Korean Workers’ Party supporting the call to arms for their Vietnamese allies. The regime in Pyongyang brought the conflict in Vietnam to the front steps of North Korean factories, farms, and other work places via its print media. A 6 April, 1965, headline in the Rodong Sinmun proclaimed, “Let’s actively support the Vietnamese peoples’ struggle!” while statements from North Korean steel mill workers and coal miners in the same section respectively announced, “Socialist countries have the right and duty to support the Vietnamese people” and “We are all prepared to run into South Vietnam at any time.” A group of workers and students from Kaesong were even more fanatical in their support for their Vietnamese comrades as they signed a pledge to assist “the fighting Vietnamese people” as a volunteer force.[8]

The DPRK’s state media also brought the Vietnam War into the North Korean home. On 7 April, 1965, the first vice chairman of the Korean Democratic Women’s Union, Kim Ok-sun, declared in a Rodong Sinmun column, “Korean women will send their husbands, sons, and daughters, as volunteer forces to support the Vietnamese people.”[9] Kim Ok-sun urged the North Korean leadership to send their “beloved husbands, sons, and daughters” to the Vietnamese front “in order to support the South Vietnamese people and women who are fighting the US imperialists.” A few months later, after ROK President Park Chung Hee decided to send another division of South Korean soldiers to Vietnam, Kim Ok-sun released a statement in which she said, “The more the US aggressors step up their dirty war machinations in Vietnam, the firmer the Korean women will stand by the heroic Vietnamese people and women and give active support and encouragement to their struggle.”[10] In this case, the North Korean mother, represented in the DPRK’s propaganda as the most revolutionary female archetype, sacrifices for the collective wellbeing of the international revolutionary movement.[11]

The Korean Democratic Women’s Union proclaimed solidarity with Vietnamese women. The Vice-Chairman of the of Korean Democratic Women’s Union Choi Geum-ja traveled to North Vietnam in the mid-1960s and visited factories, mills, farms, schools, and hospitals. Choi said she was particularly moved by the “heroic struggle of Vietnamese women.” She explained, “The women of Vietnam are unfolding an extensive Three Ready’s Movement. It is a movement to engage themselves in productive labor in place of their husbands, brothers, and sons who have gone to fight, take good care of the family members of service members, and get themselves ready to fight when necessary.” Choi proudly recalled stories of selfless Vietnamese women assisting the Vietnamese struggle. For example, she fondly remembered the female workers of the Namdinh textile factory raising their production quotas despite attacks from the “US air pirates” and a 53-year old woman in Quangdinh province who secretly ferried munitions across a river forty-five times in three days despite heavy bombing.[12]

The Korean Democratic Women’s Union also sent telegrams to the South Vietnamese Liberation Women’s Union and praised “the South Vietnamese women for taking an active part in the heroic anti-US national salvation struggle with the entire people.”[13] Despite their seemingly genuine attempt to promote the importance of women in the Vietnamese struggle for national liberation, the Korean Democratic Women’s Union couched their support in language that emphasized the traditional maternal role of women during wartime. Rather than encourage Vietnamese women to take up arms, the North Koreans noted the significance of women in non-combat roles, such as in the home and the workplace. North Korea’s focus was on liberating Vietnam the nation, not the women of Vietnam.

This outpouring of support from the North Korean masses for the Vietnamese struggle, as represented in the DPRK’s state media, indigenized the threat of a US invasion and propagated the notion that Washington was intent on destroying Third World socialism. As the domestic mobilization campaign for the Vietnam War effort intensified in the DPRK, petitions to join a “volunteer force” frequently appeared in the Rodong Sinmun. On 10 April, 1965, the Rodong Sinmun reported on the continuation of petitions to fight in the Vietnam War by the people of Hyesan and Wonsan.

The mobilization campaign led up to a visit by a delegation of the South Vietnamese National Liberation Front in May 1965. According to the Czechoslovak ambassador to the DPRK, the delegation “received a grandiose welcome… and huge gatherings were organized in Kaesong, Wonsan and Pyongyang in honor of the delegation.” The delegation’s leader, National Liberation Front Central Committee member Nguyen Van Hieu, also gave a speech at the Third Supreme People’s Assembly meeting in Pyongyang. In the speech, Nguyen said:

The entire South Vietnamese people and army always draw a lofty inspiration from the powerful, enthusiastic and active assistance, material and moral, that the government of the DPRK and the fraternal Korean people have rendered and will continue to render the South Vietnamese people in their just patriotic struggle for driving out the US imperialist aggressors, liberating South Vietnam, and achieving reunification of the fatherland.

Nguyen added that the North Korean peoples’ “lofty internationalist spirit of resolutely defending the world people’s revolutionary struggle and national liberation” serves as a valuable lesson for South Vietnam.[14]

The Czechoslovak ambassador to the DPRK commented on the domestic situation in North Korea during this period of close Vietnamese solidarity and said, “Instead of mobilization to accomplish work goals, all attention is focused on foreign policy issues, combat readiness and unity of Asian and African countries.” He said that his “friends,” most likely referring to other Eastern European diplomats stationed in Pyongyang, also noticed that this North Korean government-led campaign was intended “to distract people from pressing economic problems and to drown internal difficulties in similar actions.”[15] Diplomats of Eastern bloc countries believed the DPRK’s Vietnam War mobilization campaign was designed to distract North Koreans from domestic issues. As the East German Embassy in Pyongyang observed in June 1965: “There is an increasing level of war psychosis among the [North Korean] people. For instance, one advises friends not to buy a table or a wardrobe since a war is imminent.”[16] The North Korean government used the Vietnam War as a means to instill fear into North Korean society. This fear united North Koreans around their “Dear Leader” who supposedly protected them from US aggression.

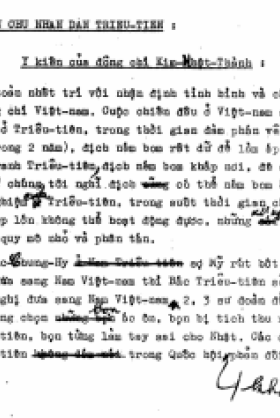

In the summer of 1965, Kim Il Sung met North Vietnamese Deputy Prime Minister and Politburo member Le Thanh Nghi in Pyongyang.[17] During their conversation, Kim offered large amounts of North Korean assistance to the Vietnamese and explained, “We are determined to provide aid to Vietnam and we do not view such aid as constituting a heavy burden on North Korea. We will strive to ensure that Vietnam will defeat the American imperialists, even if it means that North Korea’s own economic plan will be delayed.”[18] Kim’s rhetoric was backed up by action, as the East German Embassy in Pyongyang soon thereafter reported that the DPRK government had started taking out 1,000 won from North Korean workers’ wages in order to support the war in Vietnam.[19] Kim Il Sung also offered advice to his Vietnamese ally based on his prior experience fighting the Americans during the Korean War and stressed the importance of building underground facilities. He said, “Based on Korea’s experience, you should build your important factories in the mountain jungle areas, half of the factories inside the mountains and half outside — dig caves and place the factories half inside the caves and half outside.” Kim extrapolated on the process involved in building caves and tunnels. He explained, “Building a factory in a cave, such as a machinery factory, will require a cave with an area of almost 10,000 square meters. It took North Korea from 1951 to 1955-1956 to finish building its factories in man-made caves, but today we can do the work faster.”

Kim offered Nghi 500 North Korean experts and workers to help the Vietnamese build caves and tunnels. Kim noted that building caves for aircraft was far more cumbersome. He said, “Building caves for aircraft (a regiment of thirty two jet aircraft) is much more difficult, but we have good experience in this area, and our Chinese comrades who were sent here to learn how to do this have gone back home and have successfully built such caves.” North Korea’s expertise in cave and tunnel building earned them a niche within the Eastern Bloc. Even superpowers, such as China, sought North Korean assistance on these matters. After meeting with Kim, Nghi concluded in his report, “The North Korean leaders were very honest and open; they expressed total agreement with us; and their support was very straightforward, honest, and selfless.”[20] While the Czechoslovak ambassador to the DPRK viewed the North Korean government’s mobilization campaign as motivated by self-interests, Nghi relayed the message back to Hanoi that the North Koreans were entirely “selfless” and dedicated to aiding the Vietnamese struggle against the Americans.

While it is unclear if the North Vietnamese ever took up Kim Il Sung’s offer to send ground forces, North Korea did send large amounts of construction materials, tools, and automobiles to North Vietnam via Chinese railways in Fall 1965.[21] North Korea’s Foreign Economic Administration organized this arrangement with the assistance of the Chinese Embassy in Pyongyang. Beijing sometimes would not charge for the use of their railways or would say the North Vietnamese needed to pay only the shipping costs.[22] As the US embassy in Moscow aptly described in November 1967, Kim Il Sung felt “that one’s position on Vietnam is [a] touchstone for judgment on whether one is resolutely combatting imperialism and actively supporting [the] liberation struggle.”[23]

In September 1966, North Korean request to send an air force regiment to Vietnam was finally approved by Hanoi. According to an official Vietnamese People’s Army historical publication, “The request stated that their personnel [North Korea] would be organized into individual companies that would be integrated into our air force regiments, that they would wear our uniforms, and that they would operate from the same airfields as our air force.”[24] A protocol agreement signed between the two communist governments stipulated that North Korea would send enough specialists to man a Vietnamese MiG-17 company in Fall 1966 and then later in the same year, would send another group of pilots to command a MiG-17 company. If Vietnam was able to gather enough aircraft, the North Koreans would send another group of specialists in 1967 to man a MiG-21 company.[25] According to a retired North Vietnamese major general who had worked with the North Koreans, a total of eighty-seven air force personnel from the DPRK served in North Vietnam between 1967 and early 1969.[26]

The deployment of North Korean pilots to aid the North Vietnamese was kept secret to the general public until 2000.[27] However, a high-ranking North Korean defector, who previously served as vice president for North Korea’s state run news agency, told the United Nations Armistice Commission in 1967 that Kim Il Sung had secretly sent around 100 pilots to Vietnam. The French Foreign Ministry, which kept close tabs on its former colony in Southeast Asia, said this information suggests “Pyongyang is not content to just verbally support the opponents of the US in Vietnam.” The French also noted that “Marshal Kim Il Sung himself repeatedly recommended the sending of volunteers to Vietnam by all socialist countries” and that he declared in December 1966 that North Korea was going to bring “even more diverse forms of active aid to the Vietnamese people.” However, the French concluded, “It seems difficult, from these too few pieces of info, to speak of a true North Korean commitment to the National Liberation Front or North Vietnamese sides.”[28] During the war, the DPRK’s relatively large amounts of assistance to the Vietnamese communists were kept relatively secret.

Nonetheless, North Korea did not escape the death and destruction of the Vietnam War. Fourteen North Korean Air Force personnel died in the conflict and were subsequently buried in the Bac Giang Province of Vietnam.[29] US bombs also reportedly damaged the North Korean embassy in Hanoi on 19 May, 1967. The North Korean ambassador showcased rocket shrapnel and photos of this “US criminal act” during a 20 May, 1967, press conference as evidence of further US barbarity in Vietnam.[30] In that same month, a Soviet report described the degree of cooperation between Hanoi and Pyongyang during the war. The Soviet memo said, “The DPRK is developing active political, economic, and cultural ties with the DRV [Democratic Republic of Vietnam] and vigorously supporting and helping fighting Vietnam.” The memo explained that the DPRK had sent around one hundred pilots to North Vietnam along with large amounts of free aid in 1966.

In addition, 400 North Vietnamese students were attending universities in the DPRK on North Korean government scholarships with an additional 200 North Vietnamese students expected to arrive soon. On 12 March, 1966, teachers and students at Kim Il Sung University in Pyongyang held a meeting in support of the Vietnamese struggle. A Vietnamese student studying at Kim Il Sung University gave a speech at the meeting in which he said, “The Vietnamese people will fight resolutely until they drive the US aggressors out of South Vietnam and win a final victory.”[31]

However, like other Eastern European socialist countries, the Soviets saw the DPRK’s active assistance to Hanoi as being primarily motivated by self-interest. As the May 1967 Soviet memo states, “It should be taken into account that the Korean comrades view the Vietnamese events primarily from the point of view of their possible consequences for Korea.” The memo continues, “In their opinion, the security of the DPRK, an expansion of the aggression of the American imperialists in Asia, and the prospects for the revolutionary movement in South Korea depend to a large degree on the outcome of developments of the war in Vietnam.”[32]

This observation by the Soviets was not necessarily wrong, as Kim Il Sung had previously told the Chinese that he saw the failure of US actions in Vietnam as the beginning of the end to US imperialism in Asia. In August 1965, Kim bluntly told a visiting Chinese Friendship Delegation, “If the American imperialists fail in Vietnam, then they will collapse in Asia.” Kim then went on to say, “We are supporting Vietnam as if it were our own war. When Vietnam has a request, we will disrupt our own plans in order to try to meet their demands.”[33] Kim strategically used the Vietnam War as a way to weaken the US military presence in Asia, unite his fellow countrymen around an outside threat, and display his commitment to world revolution m thereby enhancing his prestige as a leading international communist figure. In addition, Kim believed North Korea served as a useful model for postwar Vietnam. As the US embassy in Paris reported in August 1967, “Kim Il Sung offers his country’s rapid reconstruction as an example to the Vietnamese whom he urges to perform a similar feat after the United States is defeated.”[34] In 1967, the North Korean leader was already predicting America’s defeat and planning the postwar development of a reunified Vietnam.

In addition, there is evidence that Kim Il Sung advocated for a greater North Korean military presence in Vietnam as a way to assess South Korea’s military capabilities. A delegate of the Vietnamese National Liberation Front, Nguyen Long, told a Romanian diplomat in Pyongyang that “the North Koreans had plenty of people active in South Vietnam.” Nguyen Long continued, “They are active in those areas where South Korean troops are operating, so as to study their fighting tactics, techniques, combat readiness and the morale of the South Korean Army, and to use propaganda against the South Koreans.” According to Nguyen Long, the North Koreans wanted to send more personnel to South Vietnam but language barriers impeded communications between North Koreans and the Vietcong.[35] In an effort to portray Seoul as an inherently aggressive force in the Third World, North Korean officials would tell African governments that South Korea sent troops to Vietnam in order to start World War III.[36] However, in actuality, the Vietnam War presented a unique opportunity for Kim Il Sung in evaluating South Korea’s military without directly engaging them in an all out war on the Korean peninsula. The Vietnam War served as a useful litmus test for the North Korean military and intelligence.

***

While the North Koreans contributed relatively large amounts of aid to the Vietnamese struggle, the harmonious relationship between Hanoi and Pyongyang only lasted until the end of that conflict. Hanoi would soon grow tired of North Korea’s rigid stances in international forums and collusion with the Chinese in ousting the North Vietnamese from positions of power within the Non-Aligned Movement. However, as this working paper describes, Kim Il Sung actively assisted the Vietnamese struggle as a way to further his own interests and contribute to the world revolution. Although Ho Chi Minh did not permit Kim Il Sung to send ground forces to Southeast Asia, the North Korean leader mobilized his citizens to defend Vietnam and called for volunteers to help fight the Americans in Vietnam. This Vietnam War mobilization campaign reinforced Kim Il Sung’s authority domestically and paved the way for the consolidation of his absolute autocracy.

The views expressed in this Working Paper are the author’s alone and do not reflect the viewpoints of the US Naval War College, the US Department of Defense, or the US government.

[1] In his article on East Germany’s relations with SWAPO, Toni Weis said, “Solidarity discourse [with Africa] also became a means for GDR citizens to affirm their support for the political system.” See Toni Weis, “The Politics Machine: On the Concept of ‘Solidarity’ in East German Support for SWAPO,” Journal of Southern African Studies vol. 37, no. 2 (2011), 364.

[2] For those that have tied the DPRK’s seizure of the USS Pueblo with North Korea’s support of Vietnam, see Barry K. Gills, Korea versus Korea: A Case of Contested Legitimacy (London: Routledge, 1996), 110; Yongho Kim, “North Korea’s Use of Terror and Coercive Diplomacy: Looking for Their Circumstantial Variants,” The Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 2002), 8-9; Narushige Michishita, North Korea’s Military-Diplomatic Campaigns, 1966-2008 (London: Routledge, 2010), 22-23; Kook-Chin Kim, “An Overview of North Korean-Southeast Asian Relations,” in Park Jae Kyu, Byung Chul Koh, and Tae-Hwan Kwak, eds., The Foreign Relations of North Korea (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1987).

[3] Journal of Soviet Ambassador to the DPRK A.M. Puzanov for 1 August 1957,” AVPRF F. 0102, Op. 13, P. 72, Delo 5, Listy 165-192, translated for NKIDP by Gary Goldberg, accessible at http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/115641.

[4] “Amid Warm Welcome of Chinese and Vietnamese Friends,” Korea Today No. 33, 1959 (Pyongyang: DPRK Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1959).

[5] “Chosŏn inminŭn hyŏngjejŏng wŏllam inminege mugirŭl modŭn p’ohamhan hyŏngt’aeŭi chiwŏnŭl tahal kŏshimyŏ yoch’ŏngi issŭl kyŏngue chiwŏn’gunŭl p’agyŏnhanŭn choch’irŭl ch’wihal kŏshida,” 27 March, 1965, Rodong Sinmun.

[6] Jian Chen, Mao’s China and the Cold War (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001).

[7] Merle Pribbenow, “North Korean Pilots in the Skies over Vietnam,” Wilson Center NKIDP e-Dossier No. 2, < https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/north-korean-pilots-the-skies-over-vietnam > (Accessed 26 July, 2017).

[8] “Wŏllam inminŭi t’ujaengŭl chŏkkŭng chiji sŏngwŏnhaja!” 6 April, 1965, Rodong Sinmun.

[9] “Chosŏn nyŏsŏngdŭrŭn namp’yŏn’gwa adŭlttaltŭrŭl nambu wŏllam inminŭl chijihanŭn chiwŏn’gunŭro ttŏna ponael kŏshida,” 7 April, 1965, Rodong Sinmun.

[10] “Call for Resolute Action: Kim Ok Sun,” 29 July, 1965, The Pyongyang Times.

[11] Sonia Ryang explains, “An interesting point to note is that a revolutionized female figure is not depicted as a woman as such in North Korea’s discourse, but as a mother.” See Sonia Ryang, “Gender in Oblivion: Women in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea),” Journal of Asian & African Studies vol. 35, no. 3 (2000), 336.

[12] “Fighting Vietnam, Heroic People,” 17 March, 1966, The Pyongyang Times.

[13] “Greetings to South Vietnam Liberation Women’s Union,” 17 March, 1966, The Pyongyang Times.

[14] “S. Vietnamese People Are Powerful Enough to Prevail Over US Imperialism,” 27 May, 1965, The Pyongyang Times.

[15] “On the Development of Situation in DPRK in May 1965: Political Report No. 8 ,” 27 May, 1965, State Central Archive, Prague, translated by Adolf Kotlik, accessible at http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/116743.

[16] “Report about Information on North Korea from 24 June 1965,” 28 June, 1965, SAPMO, translated for NKIDP by Bernd Schaefer, accessible at http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/111821.

[17] Pierre Asselin, “Le Thanh Nghi’s Tour of the Socialist Bloc, 1965: Vietnamese Evidence on Hanoi’s Foreign Relations and the Onset of the American War,” CWIHP e-Dossier no. 77 (November 2016), https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/le-thanh-nghis-tour-the-socialist-bloc-1965.

[18] “Lê Thanh Nghị, ‘Report on Meetings with Party Leaders of Eight Socialist Countries’,” 1965, 8058 – “Báo cáo của Phó Thủ tướng Lê Thanh Nghị về việc gặp các đồng chí lãnh đạo của Đảng và Nhà nước 8 nước xã hội chủ nghĩa năm 1965,” Phủ Thủ tướng, Vietnam National Archives Center 3 (Hanoi), obtained by Pierre Asselin and translated by Merle Pribbenow, accessible at http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/134601.

[19] “Report about Information on North Korea from 24 June 1965,” 28 June, 1965.

[20] “Lê Thanh Nghị, ‘Report on Meetings with Party Leaders of Eight Socialist Countries’,” 1965.

[21] “Cable from the Chinese Embassy in North Korea to the Foreign Ministry, ‘On the Transportation of North Korea’s Material Aid for Vietnam’,” 2 November, 1965, PRC FMA 109-02845-03, 33, translated by Charles Kraus, accessible at http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/118696.

[22] “Cable from the Chinese Embassy in North Korea, ‘Supplement to the Cable of 25 September 1965’,” September 26, 1965, PRC FMA 109-02845-01, 4, translated by Charles Kraus, accessible at http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/118779.

[23] Telegram, From AmEmbassy, Moscow to SecState, Subject: North Korea, 14 November, 1967. Folder POL 7, KOR N, 1/1/67. Box 2262. RG 59: General Records of the Department of State, Central Foreign Policy Files 1967-1969, Political and Defense, POL 7 KOR N to POL 7 KOR N. NARA II.

[24] “General Vo Nguyen Giap’s Decision On North Korea’s Request to Send a Number of Pilots to Fight in Vietnam,” 21 September, 1966, excerpt from The General Staff During the Resistance War Against the United States, 1954-1975: Chronology of Events, obtained and translated by Merle Pribbenow, accessible at http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/113925.

[25] “Signing of a Protocol Agreement for North Korea to Send a Number of Pilots to Fight the American Imperialists during the War of Destruction against North Vietnam,” 30 September, 1966, Vietnam Ministry of Defense Central Archives, Central Military Party Committee Collection, File No. 433, obtained and translated for NKIDP by Merle Pribbenow, accessible at http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/113926.

[26] Pribbenow, “North Korean Pilots in the Skies over Vietnam,” NKIDP e-Dossier No. 2.

[27] Pribbenow, “North Korean Pilots in the Skies over Vietnam,” NKIDP e-Dossier No. 2.

[28] “Pyongyang’s Attitudes Towards The Conflict in Vietnam,” 7 June, 1967, Asie-Océanie, Corée du Nord Période 1956-1967, série 11, Politique étrangère, Carton 11-23-1, vol. 4 (3), Politique étrangère: Fichier général-Conflit du Vietnam, French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Housed at National Institute of Korean History, Gwacheon, South Korea, Box MU0000540.

[29] Pribbenow, “North Korean Pilots in the Skies over Vietnam,” NKIDP e-Dossier No. 2.

[30] “Savingram No. 19, North Korea: Summary of Recent Developments, May 1967,” Canadian Dept. of External Affairs, Political Affairs - Policy and Background - Foreign Policy Trends - North Korea, Vol.2, 1966/09 / 14-1969 / 06/31 (File: 20-N KOR-1-3). Electronically housed at National Institute of Korean History, Gwacheon, South Korea.

[31] “Pyongyang Students Support Vietnamese People’s Struggle,” 17 March, 1966, The Pyongyang Times.

[32] “A 7 May 1967 DVO Memo about Intergovernmental Relations between the DPRK and Romania, the DRV, and Cuba,” 7 May, 1967, AVPRF f. 0102, op. 23, p. 112, d. 24, pp. 39-42, obtained by Sergey Radchenko and translated by Gary Goldberg, accessible at https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/116701.

[33] “Record of Conversation between Premier Kim and the Chinese Friendship Delegation,” 20 August, 1965, PRC FMA 106-01479-05, 46-51, translated by Charles Kraus, accessible at http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/118795.

[34] Airgram, From AmEmbassy, Paris to DeptState, Subject: Le Monde Series of Articles on Korea, 7 August, 1967. Folder Pol Kor N 1/1/67. Box 2261. RG 59: General Records of the Department of State, Central Foreign Policy Files 1967-1969, Political and Defense, Pol 32-4 KOR/UN to POL KOR N. NARA II.

[35] “Telegram from Pyongyang to Bucharest, No. 76.247,” 6 July, 1967, Romanian Foreign Ministry Archive, obtained and translated by Eliza Gheorghe, accessible at http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/113927.

[36] Telegram, From AmEmbassy, Abdijan to SecState, Subject: None, 31 May, 1967. Folder POL 7, KOR N, 1/1/67. Box 2262. RG 59: General Records of the Department of State, Central Foreign Policy Files 1967-1969, Political and Defense, POL 7 KOR N to POL 7 KOR N. NARA II.

Author

North Korea International Documentation Project

The North Korea International Documentation Project serves as an informational clearinghouse on North Korea for the scholarly and policymaking communities, disseminating documents on the DPRK from its former communist allies that provide valuable insight into the actions and nature of the North Korean state. Read more

History and Public Policy Program

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

Cold War International History Project

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more

Hyundai Motor-Korea Foundation Center for Korean History and Public Policy

The Center for Korean History and Public Policy was established in 2015 with the generous support of the Hyundai Motor Company and the Korea Foundation to provide a coherent, long-term platform for improving historical understanding of Korea and informing the public policy debate on the Korean peninsula in the United States and beyond. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

North Korean Pilots in the Skies over Vietnam