The social and labor audit business is expanding rapidly as buyers or brands require their suppliers to pass audits that check on supplier compliance with labor and environmental laws. Some buyers require their suppliers to comply with more than minimum labor or environmental standards.

Auditors from the French Bureau Veritas, the UK firm Intertek, and TÜV Rheinland in Germany act as private investigators and issue certifications that suppliers use to satisfy buyers that they are in compliance with labor and environmental standards.

Producers or suppliers such as farms and factories pay for audits, which often last a day and cost $1,000 to $2,000. Auditors typically tour the workplace, review payroll records and other documents, and interview selected workers before submitting their reports to the auditing organization that issues the certification attesting to compliance for suppliers who pass the audit test.

Audits for compliance with labor laws typically last a day and cost $1,000 to $2,000

As more buyers demand audits of and certifications from their suppliers, audit consulting businesses have developed to pre-check workplaces to ensure they are in compliance with the buyer’s standards. Consultants sometimes guarantee that the supplier will pass the audit and accompany auditors when they visit workplaces, review documents, and interview workers, raising fears of pressure on auditors to pass suppliers.

Auditors can be pressured to approve suppliers despite deficiencies so that their firm is selected to perform future audits, and auditors can accept bribes to certify non-compliant firms. Most auditors do not have time to check whether the payroll and other documents they review are true or are false. Audit data are private, and auditors typically sign non-disclosure agreements that bar them from discussing the results of their audits with enforcement agencies and other parties; only the firm being audited and the buyer get the results.

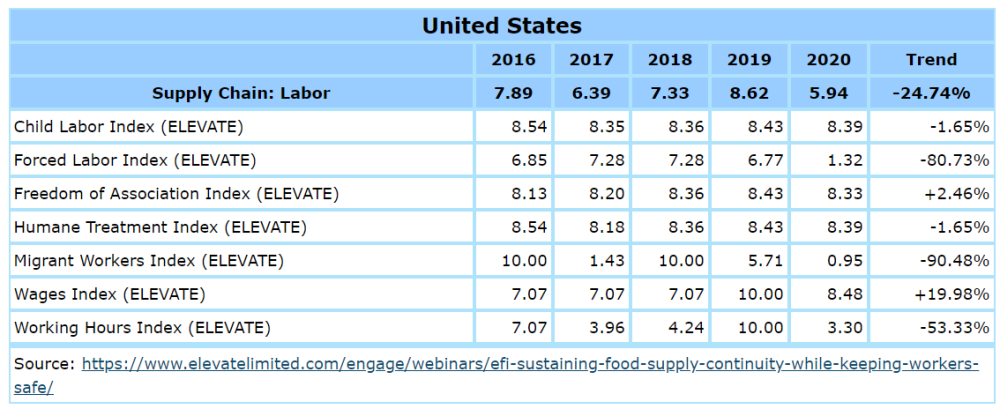

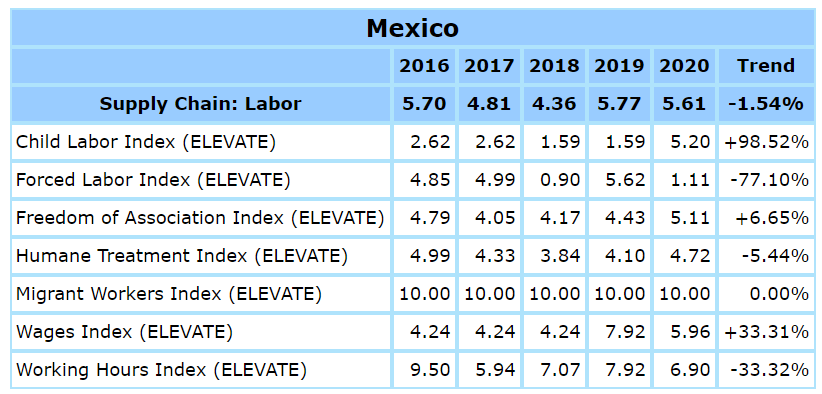

Elevate audits over 14,000 workplaces a year in 30 countries, and five percent or 700 of its annual audits are in agriculture. Elevate uses its audit data to construct relative measures or indexes of compliance with labor standards, including child and forced labor, wages, and working hours that range from zero (worst) to 10 (best). National farm samples are much smaller than Elevate’s samples of firms in apparel and electronics. Since only a few farms are audited, the relative ranking of a country’s farm labor system can fluctuate significantly from year-to-year as a result of what auditors found and because farm labor conditions in other countries got better or worse.

Elevate reported that the relative position of farm labor in Mexico and the US declined between 2016 and 2020, while the Mexican ENOE and the US NAWS show improving farm labor conditions. Elevate does not report the number of farms audited in each country, but 700 farm audits a year in 30 countries suggests an average 23 audits per country. More likely, there were more audits in some countries than others. Elevate has a reliability index for its rankings, and the reliability of the farm labor index is low because relatively few farms are audited.

The Elevate data show that the relative ranking of farm labor conditions in Mexico and the US changes sharply from year to year, with the US ranking 10 or best in one year and 1 or bad the next year for the same indicator. The US ranking on forced labor fell between 2016 and 2020, while the US ranking on wages rose.

Elevate data are not statistical data drawn from a random sample of farms. Statistical and labor law enforcement data show declining child labor employment in agriculture. Elevate’s ranking shows Mexico falling in child labor before rising in 2020, while the US child labor ranking was stable. The farm labor working hours index declined in both Mexico and the US, suggesting a worsening of these countries’ positions. It is important to emphasize that relative rankings of farm labor systems do not measure trends in farm labor conditions within a country over time.

Elevate farm audit data show declining farm labor conditions in Mexico and the US

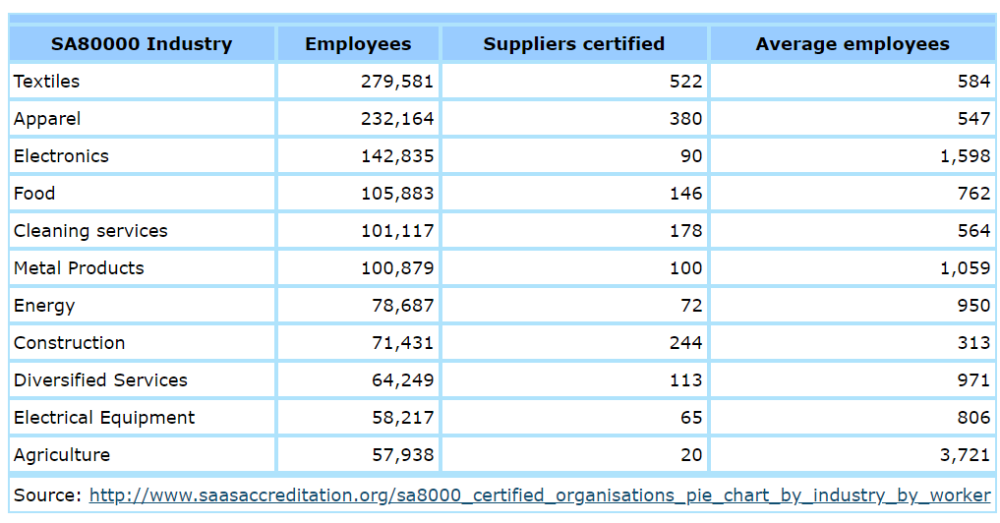

Social audits as a form or private labor law enforcement are controversial. Journalist Hengeveld notes that the NGO Social Accountability International (SAI) created the SA 8000 standard to ensure that suppliers satisfy minimum wage, health and safety, and other labor standards to minimize the “brand pressure, cheating, and corruption that is seen in the social auditing industry today.” However, Hengeveld emphasizes that for-profit audit firms have more incentive to help suppliers to pass the audit and win future auditing business than to protect the workers employed by the supplier.

The table below presents data from the Social Accountability Accreditation Services (SAAS), which emerged from SAI. SAAS has certified 20 suppliers in agriculture that have an average 3,700 employees, the highest average employment of any supplier in any industry.

Many researchers are critical of the social audit industry. LeBaron et al (2017) concluded that “two decades of evidence [find] that audit programs generally fail to detect or correct labor and environmental problems in global supply chains…[instead] the audit regime continues to respond to and protect industry commercial interests.” Terwindt and Saage-Maass and Sethi Sand Rovenpor are similarly critical of private audits, concluding that only unions and effective government inspection can ensure labor law compliance because auditors are captured by the suppliers who pay them.

As social and labor audits spread at the behest of buyers who want certification that their suppliers are complying with labor laws, audit data provide a potentially rich source of data on farm-level labor conditions. However, until there are clear definitions of variables, and transparency about the underlying data, statistical and administrative data remain the most reliable data to chart farm labor conditions.

Sources:

Author

Mexico Institute

The Mexico Institute seeks to improve understanding, communication, and cooperation between Mexico and the United States by promoting original research, encouraging public discussion, and proposing policy options for enhancing the bilateral relationship. A binational Advisory Board, chaired by Luis Téllez and Earl Anthony Wayne, oversees the work of the Mexico Institute. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

360° View of How Southeast Asia Can Attract More FDI in Chips and AI