A blog of the Kennan Institute

BY EKATERINA KRONGAUZ

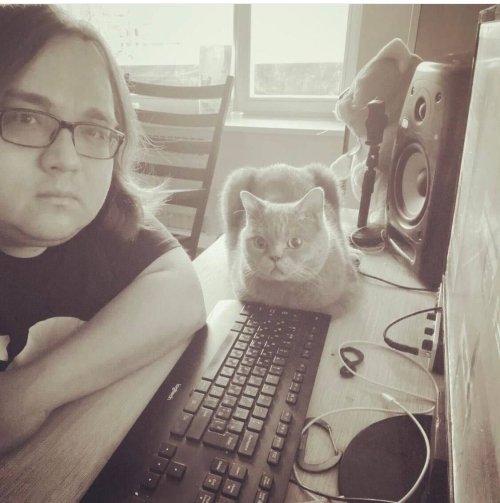

Ildar, 35; Zhenya, 28

Ildar greeted the New Year of 2022 with his partner, Zhenya, a dog, and two cats in their apartment in Moscow. Two years earlier they had moved to Moscow from Noyabrsk (a city of 100,000 people 3,000 kilometers from Moscow), and in the fall of 2021 they took out a fifteen-year mortgage for 7 million rubles (U.S. $100,000) with a $1,200 monthly payment, and bought their first apartment. They made some repairs and celebrated the New Year in their new home.

The move to Moscow happened spontaneously. Ildar had studied as a sound engineer at the Moscow Institute in absentia, working remotely for a podcast studio. Zhenya had her own business in Noyabrsk, a plus-size women's fashion clothing store, which she ran jointly with her mother.

“I never wanted to leave. I have always resisted it at all stages of our life. I don't like stepping out of my comfort zone. And I didn’t want to leave because I don’t know a single foreign language,” says Ildar.

When the war began, Zhenya became very ill.

Zhenya was born in Ukraine. Her family is from Ukraine, and her grandmother was still living in the city of Dobropolye, Donetsk oblast—currently a Russian-occupied territory.

“Every day we talked with my grandmother,” she says. “We packed a bag for her in case of emergency. The neighbors cleared out the basement, and we rehearsed with her over the phone going to the basement. But in the end, we managed to persuade my grandmother to go west.”

The idea to leave Russia came to Zhenya first in 2014, the year the Crimean Peninsula was annexed by Russia. Zhenya told Ildar, “All your doubts are garbage! Let’s go to Holland,” but Ildar didn’t want to leave then.

“I began to look up information on Georgia on Google—everyone was talking about Georgia,” Ildar recounts. “Visas were not needed. Living was cheap. I could not discuss this with Zhenya; she was in some kind of coma. I now understand that we generally had very little contact then. She sat and read the news on Telegram all day long.” At that moment, Ildar was afraid of a new iron curtain and the mobilization of all men; this was what scared posters on the Telegram channel. And Ildar began to discuss with Zhenya leaving Russia.

Ildar did not discuss the war or leaving Russia with his parents. “They live in a village in Bashkiria. And we didn't talk much. When I visited them, Solovyov”—a popular propagandist state TV host—“was on all the time. At the beginning of the war, my mother sent me some playful poems about poor Mother Russia, how the West kept pecking at her. I tried to explain my position to her, and she hung up. Several times I tried to talk to her, but she abruptly turned off her phone. I hadn’t seen this before—we don’t hang up on each other in our family.”

Through work acquaintances, Ildar and Zhenya learned that they could get a humanitarian visa to stay in Lithuania (Ildar is working on several sociopolitical podcasts). And Zhenya and Ildar decided to go. Ildar changed all their money at an insane rate (he managed to get a little more than €6,000), and agreed with a friend that he could rent their apartment for $250. Ildar also lined up more work for himself. “When I'm worried, I always load up on work. First, it helps not to think. Second, in this way I can calm my fears about money.”

While the visas and all the documents for two cats and a dog were being processed, Zhenya went to Noyabrsk to say good-bye to everyone. A week before leaving, Zhenya asked Ildar if he was going to say good-bye to his parents and if he understood that he might not see them for a very long time. So Ildar went: five hours one way and five hours return.

“I called them and said I would come. When I arrived, they were horrified. They thought something terrible had happened, that perhaps I was getting divorced. I said, “But what I told you doesn’t scare you?!”

As they started talking, Ildar realized that his assumptions had been wrong: “They understand everything. They understand that something bad is happening. They just think that you shouldn‘t raise your head or open your mouth.” His mother told Ildar that she was getting rid of the phones because she was afraid that they would be tapped and that Ildar would talk too much on the phone and would be arrested.

The family had never talked much about their past, but Ildar remembers some conversations: a great-grandmother and great-grandfather had been dispossessed, possibly even killed. Whether someone in the family was imprisoned Ildar does not know either, but his mother was afraid this might happen, and afraid for Ildar. “I re-posted a lot in the early days [of the war] on my social media. I remember now that I was a little afraid then. I edit various podcasts, and there were audio diaries of people in Ukraine during the bombings. It was already forbidden to say the word “war,” but all these criminal articles about discrediting the army did not yet exist. Of course, my mother was also afraid for me. But we had a good good-bye. We went to the banya with Dad,” says Ildar.

On April 29, Ildar’s father-in-law came down to Moscow and loaded into the car one suitcase each for Ildar and Zhenya, two electric guitars, two cats and a dog, and a friend who was also going to Riga, and together they made their way to the Russian-Estonian border. He dropped them off at 8 a.m., and with their suitcases, guitars and pets, Ildar and Zhenya tried to cross the border.

They were turned back. “It turned out that a humanitarian visa was not enough for us. We needed an additional letter saying that we were entering by invitation, an entry permit.” It was Easter Sunday, but Ildar managed to get such a letter, print it out, and cross the border at 8 p.m.

In Latvia

Ildar and Zhenya have been living in Latvia for four months on a Lithuanian humanitarian visa. Ildar works for a podcast studio. Zhenya volunteers at the NGO Helping to Leave and helps Ukrainian families from Mariupol who ended up in Russia get to Europe.

Ildar and Zhenya had hoped they could stay in Riga, but recently Latvian officials have begun to say that they would neither provide documents to Russian citizens nor renew existing visas.

“I don’t think about anything and I don’t plan anything. We have until April 2023. I know that Zhenya Googles at night about study visas, about Portugal. And there is even an option in Bulgaria,” says Ildar.

There is another option that Ildar does not want to think about right now. Zhenya can get a Ukrainian passport because her whole family is from Ukraine. And this means that Ildar can also get a Ukrainian passport. But then they would both have to give up their Russian passports, and they would no longer be able to visit their parents in Russia.

But with a Ukrainian passport it is easier to get European documents. It would also be possible for Zhenya alone to acquire a Ukrainian passport, and then either Zhenya's documents or Ildar’s could be used, but Ildar does not want this. Nor does Ildar want to return to Russia, or even visit.

“I don't know, I don't understand. It seems to me that no one needs me, and no one is looking for me. But I don't want to check. And I don’t want to think about all this.”

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.

Author

Independent Journalist

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Wilson Center is proud of its historic connection to the Kennan Institute and looks forward to supporting its activities as an independent center of knowledge. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in The Russia File

Browse The Russia File

Chechnya as a Model of Modern Russia

Russia’s Indigenous Communities and the War in Ukraine

Gas and Power in a Changing US–Russia Relationship