Destination: Tel Aviv

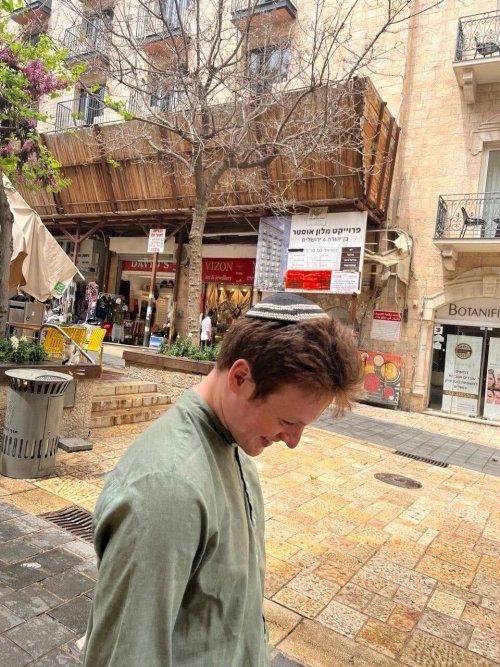

Michael, 19

A blog of the Kennan Institute

Michael, 19

“What was happening in your life when the war began?” I ask Misha, and he responds, “Which one?”

Two wars ago, Misha was preparing for final exams at a private school in Moscow. Today he works six days a week as a waiter in a Tel Aviv hotel that is taking in refugees from Sderot, the Israeli city that was almost destroyed after the start of the war. Most of the workers at this and other hotels have been dismissed, but as long as the Sderot mayor’s office pays for housing and food for internally displaced persons, Misha has a job.

As soon as the hotel residents start returning to Sderot, Misha will be furloughed out, and before being drafted into the army he will need to look for another job. But it won’t be easy. Hourly and unskilled work, of which there used to be a lot, has largely disappeared, and there is huge competition for it. Now, during the war that followed Hamas’s attack on October 7, businesses are working at half capacity, and sales of everything aimed at tourism have stopped.

Misha’s Story

Misha left a war and almost inevitable conscription into the army a dozen months ago in one country, Russia, and now lives in a war and is waiting to be drafted into the army in another country, Israel. Misha is nineteen years old. Two years ago he was planning to study history at university, living with his father and brother and hanging out with friends.

In this series of Russia File pieces about people who left the Russian war in Ukraine, I deliberately did not include Israel. Only people with Jewish ancestors who met the requirements of Israel’s Law of Return could go to live in Israel, and this is a privilege that most of the recent Russian emigrants did not have. New emigrants were entitled to six months of living payments and a year of studying Hebrew. Despite the high cost of living and a difficult adaptation period, this seemed to me a privileged path compared to the uncharted paths taken by most of those who have left Russia.

But Misha went to Israel alone. His parents received documents allowing them to leave Russia. His mother stays in Russia and travels between countries with her new husband, and Misha’s father and brother went to Latvia, where his father was offered a job. Misha was about to turn eighteen and could no longer obtain a Latvian residence permit with his father, as his younger brother did, and so they decided that Misha would remain in Israel alone.

Misha: “I knew that in the first year of repatriation you are not drafted into the army. In April 2022, we received Israeli passports, and I returned to Moscow and finished school. But in Russia there are eleven classes, and in Israel twelve. And a Russian certificate is not enough to enter a university. That’s why there is a special program that prepares you for the Israeli final exams for a year. In the end I received a good Israeli certificate, like all other Israelis. At first I thought I would go to university and not join the army, and then I would leave Israel. But gradually, while I lived here, I began to learn what the Israeli army was.

“In Russia, none of my friends serves in the army and no one wants to. It is a waste of time. And also unpleasant. Here, the army is an institution of social mobility. For the rest of your life you will be able to call on your army friends to help solve your problems. Anywhere you go you will be asked where you served. And if I served, I’m already one of them.”

In August of this year, Misha was supposed to be drafted into the Israeli army, but because of the large influx of repatriates, the draft was postponed to December. And now, with the outbreak of the Hamas-Israeli war, the draft has been postponed to March 2024. There is no one available to teach recruits and no time to do so.

On the eve of the start of the second war in Misha’s life, he returned with his girlfriend from Amsterdam, where he had met her father. On October 7, Misha slept through several loud sirens at 7 a.m., when Tel Aviv began to be shelled and the largest terrorist attack in the history of Israel unfolded in the south.

“While I was studying this year, I lived in a cheap hostel and it was covered partly by payments from the state, partly by my dad’s money. But since the draft was postponed, I got a job as a waiter in a hotel and rented a room in Tel Aviv. That Shabbat I was scheduled to work an evening shift. They deliberated for hours whether we would work or not, then in the evening they finally called me. And for the first time I went to work by taxi, though it costs about half a day’s wages.”

I ask Misha if he was scared that day, and he tells me about the sky, as if producing a classic Russian graduation essay on Tolstoy’s War and Peace on the theme of the sky over Andrei Bolkonsky, only in a modern TikTok format. “The sky was very interesting. Tel Aviv usually has very blue skies, clear and without clouds. But when I went to work, I noticed that the whole sky was covered with white stripes. These were traces of interceptions.”

“In our hotel it is forbidden to turn on the TV on Shabbat, but when I arrived it was on, and everyone was crying. It was the end of the holidays. All the residents had come to visit relatives for the holidays, and in each family someone had been killed, someone had been taken hostage; someone was at that moment in the army or had been called up with the reserves.

“The army is Israeli society. Israel is very small. The war affects every family. The hotel guests checked their flights, and all had been canceled. We helped them change their tickets. In the evening we were told that the restaurant where we worked was closed, but they let me work in another restaurant in the hotel.”

“I will spend several months of service in the ulpan [government-run language learning classes], where they teach people Hebrew, and I won’t have to do anything, and it will count as service. And now it’s been canceled.”

Becoming Israeli

On a recent day, Misha was chatting on Zoom with his classmates, some in Moscow, some in Turkey, some in Amsterdam. “We were talking, and suddenly I thought: they have never heard the stories that I have been hearing in recent weeks. They didn’t hear the rockets. They didn’t sit in bomb shelters. Where have I come? What did I leave? For what? But looking at my classmates who remained in Russia, I still think that despite what is happening now, the future of Israel is clearer to me. Russia’s lack of freedom feels heavier to me now. If I studied to be a lawyer, I wouldn’t be able to apply my knowledge, because there is no rule of law there.”

I ask Misha about his friends, quite progressive young people who defend the rights of women, minorities, the oppressed, and who are now divided in their views on the war in Israel.

“We held the same views on the war in Ukraine. And now I have to ban many acquaintances and friends on social networks. It's very simple: I became an Israeli. For some, what is happening is the fight for a free Palestine, but every day I am under rocketfire, I communicate with people who have suffered. I look at it from a different point of view. I’m not ready to join the fighting forces; after all, I’ve only been an Israeli for a year and a half, and for seventeen years I was a Russian. For another eleven years I cannot return to Russia while there is a risk of conscription into the army there. So I must be somewhere. I’m not ready to die for this country yet, but I want to become a part of Israeli society, and without the army this is impossible.”

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Wilson Center is proud of its historic connection to the Kennan Institute and looks forward to supporting its activities as an independent center of knowledge. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more