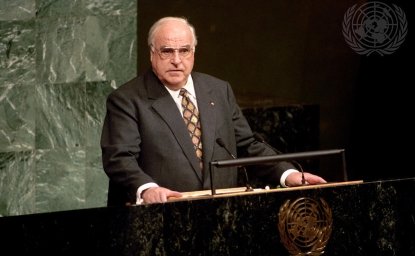

The Helmut Kohl Transcripts: Engaging Gorbachev and Yeltsin

Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin were among the leaders that German Chancellor Helmut Kohl engaged the most in the 1990s.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin were among the leaders that German Chancellor Helmut Kohl engaged the most in the 1990s.

This essay is one in a series about the Helmut Kohl Transcripts, a new Wilson Center Digital Archive resource featuring hundreds of Helmut Kohl’s foreign policy meetings with world lead

Explore the helmut kohl transcripts

Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin were among the leaders that German Chancellor Helmut Kohl engaged the most in the 1990s. Kohl often met with or phoned Gorbachev, the final leader of the Soviet Union, and Yeltsin, the first president of the Russian Federation. The Soviet Union and Russia were also constant through lines in Kohl’s meetings with the likes of George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, John Major, and other world leaders. Kohl often expressed great concern for the individual fates of Gorbachev and Yeltsin, and frequently weighed in on the domestic and international challenges facing Moscow's leadership.

The Helmut Kohl Transcripts on the Wilson Center Digital Archives features records of nine of Kohl’s meetings with Gorbachev from 1990-1991 and 14 more of his meetings with Yeltsin, dating between 1991 and 1997. Scores of other meeting memos in the Helmut Kohl Transcripts underline Kohl’s consistent concern with, and his insights into, developments in the Soviet Union and, after December 1991, Russia.

After German unification in 1990, Kohl lent his support to Mikhail Gorbachev’s political and economic reform efforts in the Soviet Union. By this time, the Soviet economy was crumbling, and internal battles raged over a new union treaty, the introduction of market reforms, and the independence of the Baltics in 1990-1991. Despite considerable turmoil in the USSR, Kohl nevertheless remained invested in Gorbachev and wished to see him stay in power. In one meeting with Gorbachev from November 1990, Kohl explained that “he could not behave like a normal viewer for whom the story [in the Soviet Union] continued.” Instead of sitting passively on the sidelines, Kohl took on an active advisory role. He was, in his own words, “betting on” Gorbachev.

In their meetings, Kohl eagerly listened to Gorbachev’s plans. He endorsed Gorbachev’s idea to introduce a greater degree of federalism and to adopt a new union treaty that promised more rights and more autonomy from the center, Moscow, for the Soviet republics. “The republics, the regions and the people should have their freedom,” Gorbachev announced in November 1990. Kohl agreed, responding that “success for President Gorbachev” in this regard “was important for Germany and for Europe.”

Aside from political reforms, Kohl also supported Gorbachev’s economic reforms and his plans to integrate the Soviet Union more deeply into the global economy. As the major benefactor of Europe’s transformation, Kohl sensed that immediate economic help was necessary for the stabilization of democracy. United Germany became the main economic supporter of reforms in Russia and Central and Eastern Europe, donating 53-percent of the overall amount of Western aid in the years to come. Kohl and Gorbachev also negotiated the scope of Germany’s financial participation in a housing program for the Soviet soldiers that were to be withdrawn from East Germany until 1994.

In January 1991, the violent oppression of the Baltic independence movement revealed the precarious state of the Soviet Union’s international cohesion. After Gorbachev sent troops to crack down on the movement for the secession of Lithuania from the USSR, the situation turned into tragedy on January 13, 1991. Soviet soldiers fired at demonstrators in Vilnius, killing 15 people. Even as there were questions whether Gorbachev was still fully in control, or whether the Soviet military had already seized power, it was increasingly challenging for Kohl to support Gorbachev’s course. “We in the West had supported Gorbachev the reformer – not Gorbachev the suppressor,” John Major pointed out in one meeting with Kohl. Kohl’s bet was not paying off.

In August 1991, a group of hardliners in the Soviet government tried to take control of the country and depose Gorbachev. They were opposed, mainly in Moscow, by a short but effective campaign of civil resistance led by Russian President Boris Yeltsin. Although the attempted coup lasted only two days, it signaled Gorbachev’s loss of power and prompted Kohl to seek out other allies in Moscow.

Kohl began to establish a rapport with Boris Yeltsin, then the President of the Russian Federal Republic as well as Gorbachev’s main democratic challenger. When Yeltsin came to Bonn for the first time in November 1991, he emphasized to Kohl that “Gorbachev had become an entirely new person after the coup.” Gorbachev was now hastily making changes to his governing approach, but Yeltsin complained that “time is running out. Plenty of time has been wasted.”

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991, Kohl did all he could to facilitate Russian reforms under Yeltsin’s leadership, even as it was unclear whether Yeltsin could prevail in a domestic constitutional fight with opposing forces in the People’s Deputy Congress. Kohl anticipated high costs for the West if Yeltsin was toppled. As such, the West had to rearm and defend itself against a reactionary Russia. Yeltsin was the best bet for Russia’s transition. Kohl’s impression was that “Yeltsin would win the game” if he received urgently needed help from the West. “If Yeltsin fell,” Kohl confided to US President Bill Clinton, “things would turn much more difficult and expensive, especially if there was a relapse into the old structures.”

Aside from engaging Gorbachev and Yeltsin on the domestic challenges facing the Soviet Union and Russia, Kohl also sought out the support or views of these two men on various international issues – including the Gulf conflict, the wars in Yugoslavia, and NATO enlargement, all of which will be the subject of future postings in this series.

Kohl also concerned himself with the nuclear legacy of the former Soviet Union. Indeed, the collapse of the Soviet Union posed the greatest nonproliferation problem since the beginning of the atomic age. What was to be the fate of the 30,000 “Soviet” nuclear weapons in Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Belarus? Political upheaval and economic hardship left warheads, delivery systems, and technology vulnerable to diversion or sale. Kohl himself raised these issues with Yeltsin, while also tasking his staff to monitor nuclear weapons present in the newly independent states.

Kohl likewise remained attentive to the safety of nuclear power plants. “Events in Kiev affected all of us,” Kohl told Leonid Kravchuk in February 1992, a reference to the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. As the host of the 1992 World Economic Summit, Kohl pushed for the establishment of a joint fund that would provide support for nuclear power plant safety. When the United States and Japan did not endorse the idea, Kohl and Mitterrand were still determined to see the initiative through to the end.

“If a nuclear power plant exploded, it would be the drama of the century,” Mitterrand noted.

Kohl and Gorbachev review the state of bilateral relations, the Gulf crisis and the situation in the Soviet Union, especially with regards to Gorbachev's perestroika and glasnost and the Soviet Union's economic reforms. They discuss Western economic assistance and food supplies for the Soviet Union as well.

Kohl and Gorbachev review the situation in the Baltics and Kohl reports on his meeting with Latvia's Prime Minister Godmanis.

The Chancellor’s [Helmut Kohl's] Telephone Conversation with President Gorbachev, 21 February 1991

Kohl and Gorbachev discuss the domestic situation in the Soviet Union as well as the struggle between Gorbachev and Yeltsin.

Kohl and Gorbachev discuss the ratification of the comprehensive German-Soviet Treaty as well as the situation in the Soviet Union.

Kohl and Gorbachev confer on the state of reforms in the Soviet Union, Western financial assistance and preparations for Gorbachev's participation in the World Economic Summit in London later in July. In addition, they discuss European security, EC enlargement and the potential enlargement of NATO.

Kohl and Gorbachev engage in an assessment of the World Economic Summit in London.

Kohl and Gorbachev scrutinize the situation in the Soviet Union after the coup. They agree on the urgent need for more for financial help.

Kohl and Yeltsin examine the situation after the coup and discuss preparations for Yeltsin's first visit to Germany in November 1991.

Kohl and Yeltsin discuss Russia-Ukraine relations, Russian debt and finance issues, the question of Volga-Germans and the release of Honecker from the Chilean embassy.

Kohl and Gorbachev talk about Ukraine's desire for independence and its ramifications. They also examine Gorbachev's ideas for further reforms in the Soviet Union.

Kohl and Gorbachev look into the situation on the eve of the Soviet Union's disintegration.

Bohl and Kozyrev talk through the potential proliferation of nuclear and chemical weapons after the demise of the Soviet Union. Moreover, they consult on the reduction of tactical and strategic nuclear weapons.

Kohl and Yeltsin debate Russia's economic reforms and the situation in the Commonwealth of Independent States as well as Western financial aid and preparations for the 1992 World Economic Summit in Munich and especially Russia's participation. Moreover, they review the prospects of Honecker's release from the Chilean embassy in Moscow.

Kohl and Yeltsin debate questions of finance and the withdrawal of "Soviet" troops from East Germany in 1994. Yeltsin expresses his disappointment about the low revenues from the sale of former Soviet property in East Germany. Kohl counters that Russia's debt rescheduling would cost Germany 8 billion DM. Moreover, he emphasizes the enormous scope of environmental damage that the former Soviet forces had been causing in East Germany.

Kohl and Yeltsin analyze the domestic situation in Russia and Yeltsin's preparations for a referendum on the constitution in 1993. Kohl raises the issue of the two very recent contradicting speeches by Russian Foreign Minister Kozyrev at the CSCE Foreign Ministers' Meeting in Stockholm. Kohl reiterates that this issue was 'very bad from a psychological standpoint" asking Yeltsin to clarify this during their joint press conference.

The Chancellor's [Helmut Kohl's] Meeting with Russian President Yeltsin on Wednesday, 3 March 1993

Kohl and Yeltsin examine Russia's domestic situation against the backdrop of its constitutional crisis and the conflict between Yeltsin and the Deputy People's Congress. Yeltsin emphasizes his willingness to resolve the conflict according to the constitution. At the same time, he does not exclude the possibility that he could be forced to "resort to extreme measures" in order to save democracy.

Kohl and Yeltsin review the results of the referendum on the Russian constitution and its implications for Yeltsin's future relationship with the parliament.

Kohl's request for Yeltsin is to put more political pressure on the Bosnian Serbs.

Kohl and Yeltsin debate the situation in Russia after end of the constitutional crisis.

Kohl and Yeltsin examine the state of bilateral relations on a number of issues including trade, culture and military-to-military contacts.

The Chancellor's [Helmut Kohl's] Conversation with Russian President Yeltsin on 9 May 1995 in Moscow

Kohl and Yeltsin discuss the parallelism between NATO enlargement and Russia's engagement and the timing of NATO enlargement in particular. Yeltsin expresses his disappointment about the lack of progress in the U.S.-Russian talks on the issue complaining that the "the West was about to relapse into the thinking of military blocs prior to 1990. This was not acceptable," Yeltsin says. Moreover, Kohl and Yeltsin discuss Russian sales of nuclear power plants for Iran.

Kohl wants Yeltsin to pressure the Bosnian Serbs into concession. Kohl's request for Yeltsin is to become engaged personally in such an effort.

Kohl and Primakov debate NATO enlargement. Primakov reiterates the broad societal consensus against NATO enlargement in Russia. Kohl stresses that there was Western agreement in terms of the need for Russia's continued inclusion in international affairs.

Kohl and Yeltsin discuss the need for an end to the war in Chechnya prior to the 1996 Presidential election in Russia. Yeltsin criticizes the sharp position of the German media in terms of the Chechnya War. With regards to NATO enlargement and the NATO-Russia partnership, Kohl and Yeltsin agree to search for a solution after the Russian Presidential election.

Kohl and Yeltsin talk about the convocation of regular German-Russian summits including their relevant ministers. They review Yeltsin's meeting with Clinton in Helsinki on NATO enlargement in March 1997 when Yeltsin gave his consent to the conclusion of a NATO-Russia partnership treaty based on the condition that NATO would not deploy nuclear armaments and permanent conventional forces in its new member states. Kohl points to the long-term perspective and the importance of concluding the NATO-Russia Founding Act.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more