Taylor & Francis’ Cold War Eastern Europe (CWEE) is an electronic database that provides access to over 13,000 digitized, searchable, and downloadable files. Created by the Northern, Southern, Central, and Western Departments of the British Foreign Office (FO) and by the East European and Soviet Department of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), these documents were sourced from the FO 371, FCO 28, and FCO 33 series of the National Archives, UK.

As such, they are focused on Britain’s political, economic, and cultural relations with the USSR and Eastern Europe from 1953-1975. However, these sources also provide valuable insights into Communist regimes’ interactions with third countries. Full access to the CWEE materials is limited to institutions that have purchased access to the site, but a substantial number of read-only files are available for visitors who register for a free trial.

Due to their focus on the European Communist states, the CWEE files provide information on China, North Korea, North Vietnam, and Mongolia mainly from the perspective of their political and economic contacts with the USSR and its East European satellites. Their authors – the FO in London, the British diplomats accredited to the Communist countries, and the UK delegates to NATO – devoted particularly strong and sustained attention to the Sino-Soviet rift and its impact on the global Communist camp. From 1961–1966, the total volume of CWEE materials related to the Sino-Soviet split is in the range of thousands of pages.

Compared to declassified Russian and Chinese files, many freely accessible on DigitalArchive.org, the assessments of the FO officials might appear fairly outdated. The authors usually reached their conclusions through a rigorous textual analysis of the public statements in which the Soviet and Chinese leaders expressed their views about the dispute. For instance, an exploratory minute sought to pinpoint North Korea’s shifting position between Moscow and Beijing by examining the speeches that Peng Zhen and Choe Yong-geon (Ch’oe Yonggŏn) made during the former’s visit in the DPRK. The author (correctly) observed that “Soviet failure to notice P’eng Chen’s visit to Korea…[is] abnormal and suggests strain.” Ironically, this method of analysis had much in common with the practices of the Soviet bloc diplomats stationed in Pyongyang, who meticulously counted how many articles Rodong sinmun had published on the USSR and China in a given period.

Thus, the greatest value of CWEE’s Sino-Soviet files lies in the insight they provide into the FO’s policy-making mechanism, with particular respect to the discussions that British officials held with their NATO allies on the causes and strategic implications of the Sino-Soviet split.

Despite its declared focus on the North Atlantic area, NATO paid considerable attention to the Sino-Soviet partnership as early as 1953. In October 1958, the US NATO delegation prepared a 25-page note on the “divisive and cohesive elements in the Sino-Soviet alliance,” and in 1959, it promptly informed the Committee of Political Advisers about the first rumblings of the Sino-Soviet rift, such as Moscow’s conspicuous reticence about the Chinese communes and its neutral stance on the Sino-Indian conflict. Still, the files accessible in NATO Archives Online usually appear without the confidential comments and assessments made by the various other delegates. The inclusion of such comments is one strength of the CWEE documents.

For example, a defensive brief written for Harold Macmillan’s April 1962 talks with John F. Kennedy outlined the similarities and differences between British and US approaches towards the Sino-Soviet split. It described the “lively” NATO discussions about this subject as a “useful exercise,” but cautioned that it was still “too early to say whether it will lead to the evolution of a common NATO policy towards the Sino-Soviet dispute,” not the least because Washington did not see eye to eye with London on the question of trade with China. In the FO’s view, “the willingness of the non-Communist world to trade with China in certain essential commodities…contributes to Chinese freedom to diverge from the Soviet Union and thus helps to keep the dispute alive.” Yet the authors of the brief felt compelled to acknowledge that “this argument is not likely to commend itself to the Americans.”

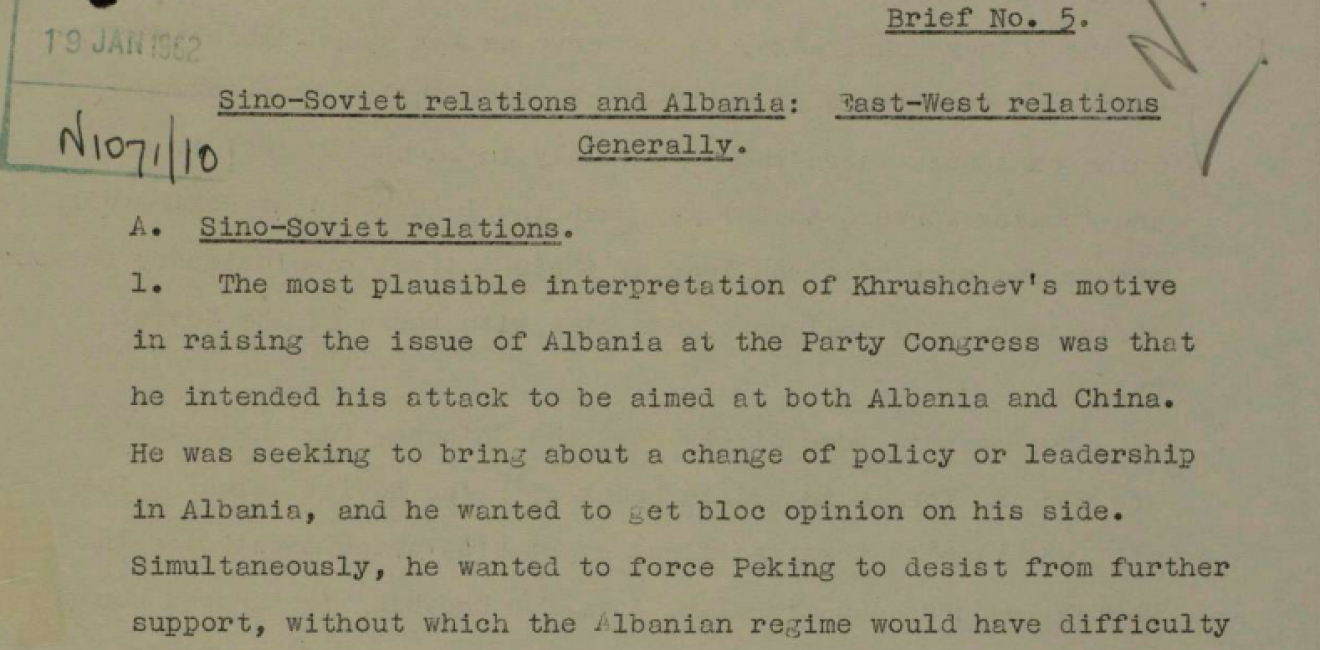

Another FO brief, written for the visit of Italian Prime Minister Amintore Fanfani (January 1962), likewise argued that “the continuation of the Sino-Soviet dispute is in the interest of the West.” While “there is little that we can do to exacerbate it,” a “Western refusal to trade with China, whether in oil or other vital imports, might…bring about at least a temporary relaxation of Sino-Soviet tension.” Thus, as far as China was concerned, the FO was more in favor of economic engagement than the US Department of State, but in the case of Albania, the British were less eager to initiate rapprochement than their Italian allies. As the brief put it, Albania’s “present position as an apple of discord in the bloc suits us very well,” but “we should not take any action which could be interpreted as running after Albania.”

Other CWEE documents reflect the FO officials’ critical views on the very process of NATO discussions on the Sino-Soviet dispute. In July 1962, Julian L. Bullard acidly remarked that the latest talks in NATO’s Political Committee “produced a very indifferent paper,” while other officials disapproved the simultaneous discussion of the topic in the Political Committee and the Information Committee, or flatly declared that discussing the dispute in NATO forums was “a waste of time.”[i]

Still, the regular exchange of opinions did stimulate creative thinking. For instance, Stephen L. Egerton read Dean Rusk’s Circular Airgram 5667 (November 22, 1962) “with great interest,” though he felt that it “oversimplifies the dispute in presenting it as primarily a question of struggle for control of the Communist bloc.”[ii] The Netherlands’ NATO delegate, Christoph van der Klaauw, astutely observed that China’s non-participation in COMECON might not have resulted from a Soviet effort to ostracize China (as Rusk suggested) but rather from Beijing’s unwillingness to join that organization.[iii] At a Political Committee meeting held in October 1965, the French, Italian, Greek, West German, and Canadian delegates were all eager to express their wildly diverging opinions about the impact that the recent Indo-Pakistani War had made on Sino-Soviet relations.[iv]

“The rigidly doctrinaire communist world is far more damaged by dissent within its ranks than is the more flexible free world,” Rusk wrote in Airgram 5667. His observation keenly grasped a key difference between NATO’s lively discussions about the Sino-Soviet split and the heavily micromanaged Interkit meetings at which the China experts of the Soviet bloc’s ruling parties analyzed (or rather castigated) Chinese domestic and foreign policies. While NATO largely failed to devise a common policy towards the Sino-Soviet dispute, at least it did not pursue coordination at the expense of analytical diversity.

[i] From the UK Delegation to NATO in Paris (Alan E. Donald) to the Foreign Office (Julian L. Bullard), June 25, 1962 (comments by Bullard and Arthur J. de la Mare on the outer cover of the file), PRO FO 371 165780 001; From the UK Delegation to NATO in Paris (Richard D. Clift) to the Foreign Office (Edward Youde), December 5, 1962, PRO FO 371 165788 001.

[ii] From the UK Delegation to NATO in Paris (Richard D. Clift) to the Foreign Office (Edward Youde), December 5, 1962 (Youde’s comments on the outer cover of the file), PRO FO 371 165788 001.

[iii] From the UK Delegation to NATO in Paris (Richard D. Clift) to the Foreign Office (Stephen L. Egerton), January 14, 1963, PRO FO 371 165788 001.

[iv] From the UK Delegation to NATO in Paris (William Marsden) to the Foreign Office (Anthony D. Loehnis), October 25, 1965, PRO FO 371 182507 001.