A blog of the Latin America Program

Q: Can you say anything about the regional dynamics of the coffee industry in Latin America?

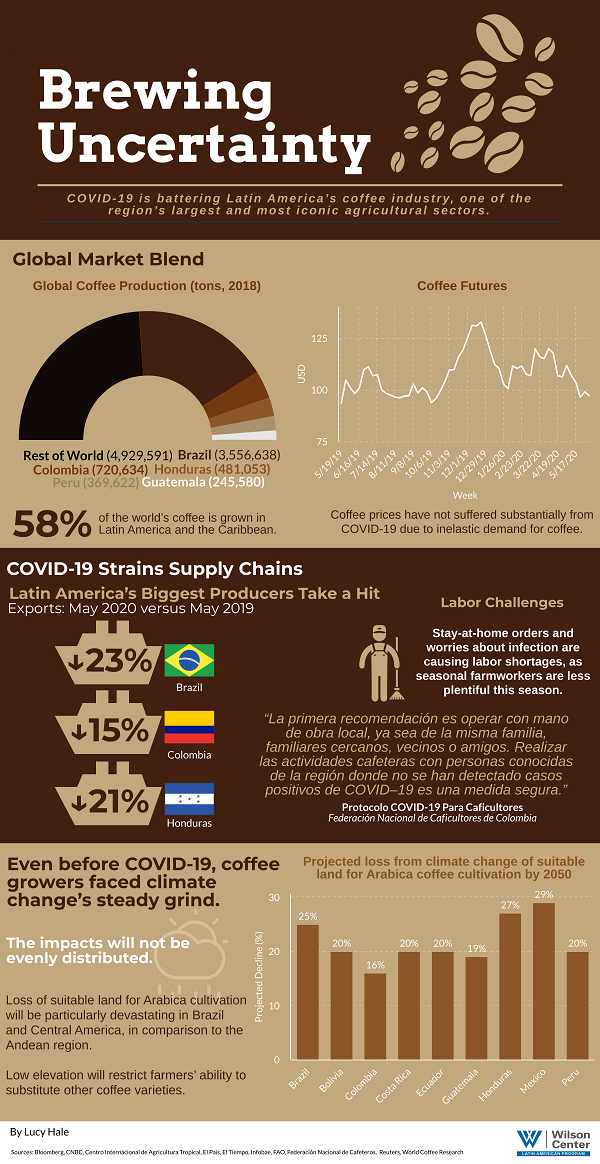

A: It is different depending on the country or region you choose. Brazil is the largest and most efficient producer in Latin America, followed by Colombia. Although the international price of coffee has been low and very volatile lately, Brazil’s production costs are the lowest in the region. At the same time, the exchange rate has allowed Brazilian farmers to have the highest income in the region — and very possibly the world. Colombia has also benefitted from its exchange rate, in part due to oil prices, on which the Colombian economy is highly dependent.

In most other Latin American countries, low coffee prices have seriously affected the income of farmers. According to coffee grower representatives in Central America, this has also contributed to migration to the United States.

Q: Hundreds of thousands of small and medium-sized producers constitute the backbone of Colombia’s coffee industry. How is climate change affecting the medium- and long-term prospects of these families’ livelihoods, and how is Colombia’s coffee industry adapting overall to the current reality of new temperature and rainfall patterns?

A: Coffee, especially Arabica, is very sensitive to climate variations. On one hand, the changes in rain patterns, cloud cover and luminosity have a very profound impact on coffee production in terms of volume and quality. Besides the fact that flowering, and hence the bean count, can be adversely affected by variations in climate, changes in such things as the levels of humidity can bring on widespread disease. For instance, high humidity can result in an increase in coffee leaf rust, while excessive drought creates the environment for the coffee berry borer to be present. Both are potentially disastrous for coffee production.

One of the most important strengths of the National Coffee Federation is its scientific research center, the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones del Café (Cenicafé). Founded in 1938, Cenicafé has developed coffee varietals that are rust resistant, as well as many methods and technologies to increase productivity and protect the environment. Cenicafé is recognized globally as one of the most sophisticated scientific centers.

We invest millions and millions in scientific research and development, sometimes with the government, the industry, other scientific centers and universities, among others.

Q: What type of coffee is being consumed now?

A: This is an issue of concern in the industry. The fear is that, in the short term, budget-conscious consumers may continue drinking coffee but switch to cheaper brands. It is also assumed that once the situation goes back to normal, demand for high quality coffee will rebound and perhaps be even be stronger. One of the polls we carried out indicated that 67 percent of participants in our webinar believe that when things go back to normal — say, by the end of 2021 —demand for specialty coffee will be the same or higher than before COVID-19. This will have an impact on high quality coffee producers such as Colombia, Guatemala, Costa Rica and Honduras, among others, who may, in the short run, not be able to reach the premiums they were expecting.

There are a number of factors that affect high value coffees: 1) Many large coffee shops that consume high quality coffee currently have very limited operation (Starbucks, Peet’s, Tim Horton’s, etc.); 2) many small and independent coffee shops and boutique roasters that purchase high value coffees may not survive the current crisis; 3) consumers may reduce their spending and move (at least temporarily) to cheaper blends; and, 4) beyond coffee shops, many restaurants, hotels, etc., that offer high value coffees may not survive or may be forced to operate with many limitations.

Q: What will happen to demand in the long term?

A: Experts believe that demand will continue being strong once the crisis is over.

Q: The coronavirus pandemic has caused massive economic pain and dislocations in Latin America and around the world. What has happened to coffee prices over these last three months? One would presume that the demand for coffee is fairly stable (at least it is for caffeine addicts like me). Has this been the case? Have prices fluctuated in response to any changes in consumption or supply chain disruptions?

A: The first thing to note is that I’ll refer to Arabica coffee, the type grown in most countries of Latin America, although Brazil has a significant production of Robusta coffee. Arabica prices are determined by the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE)) futures contract. Prices have been extremely volatile for some years now, in part due to the situation of supply and demand, but also because of financial speculation. That said, coffee prices have been mostly low for many years. In 1982, coffee prices fluctuated between $1.18 per pound and $1.41 per pound. On June 22, 2020, coffee closed at $0.98 per pound on the New York exchange. What this means overall is that—depending on such factors as domestic inflation and exchange rates—farmers in some countries have lost more than 70 percent of their purchasing power.

So far, the pandemic has not driven coffee prices downward. However, it’s too early to say how some aspects of coffee demand will behave, or the impact on producers.

Q: Since the beginning of the pandemic, how much coffee is being consumed?

A: It’s not altogether clear. Initially, there was an increase in coffee demand by roasters; but it is not clear yet if it was because of panic buying or an actual increase in consumption. When the situation goes back to normal, we will have a clearer idea. The World Coffee Producers Forum, which I lead and which gathers producers from all continents, hosted several webinars with the leaders of producing countries across the globe, and with leaders of the industry. During those events, we carried out some polls. In one poll, leaders of the biggest industry associations in the United States, Europe, and Asia offered their views on the future of the coffee industry. One interesting result is that 76 percent of attendees believe that, once things settle down, coffee production will stay the same or increase; and 60 percent believe that coffee consumption will stay the same or increase. You can watch a video of that seminar here.

Q: What are the trends in terms of sales lost or gained and in terms of the demand for coffee?

A: Again, there are no final numbers. Intuitively, there is a concern that a significant amount of revenue has been lost, but that is not so clear with respect to volume. Consumption outside the home has gone down dramatically: the cups that cost $4 to $5 are not being sold in coffee shops, hotels, restaurants, etc. The same has happened in the “institutional” category, which includes offices, schools, universities, and the like. In the early days of the pandemic, demand rose significantly. But now it looks like it is going down, back to normal. It is possible that demand increased, at least in part, because consumers were stockpiling coffee, as they did with many other products.

Q: Early on in Colombia’s lockdown, the country faced a shortage of workers to harvest the coffee crop. Has this shortage persisted? If so, what are the likely impacts for rural families in the coffee sector as well as national level? If not, how has the need for labor been met?

There was no labor shortage in Colombia, although at the beginning of the harvest in late March, there was concern that that could materialize. At this point more than 95 percent of the mid-term (“mitaca” or “traviesa”) crop has been harvested. We conduct continuous surveys to assess where things stand. More than 94 percent of farmers said in May that they had had no problems with labor.

The Colombian Coffee Federation designed very strict health protocols — many of which are being adopted by the government and other sectors now. We carried out a massive communications campaign with the motto “La Salud de Todos es Asunto de Todos.” (Everyone’s Health is Everyone’s Business). So far, the contagion rates in rural coffee areas are still low.

As for production, the “mitaca” was delayed a few weeks due to weather, and some coffee is still being picked. The expectation is that production in the first half of the year will be around 6.5 million 60 kilogram bags, which accounts for about 45 percent of the year’s production. Things can change quickly in the agricultural sector. However, if trends hold, production in 2020 should be around 14.2 to 14.6 million bags, consistent with previous years. Coffee produced should not be confused with coffee exported, since there is some consumption in Colombia.

Q: Colombia hosts the largest number of Venezuelan refugees anywhere in the world — over 1.6 million. Are Venezuelan laborers active in the coffee sector? If so, has this created friction with the domestic labor force?

A: Coffee pickers are seasonal workers. We have seen some Venezuelans, but the numbers are not massive and there are no major issues. The pandemic has led to significant restrictions in transit between municipalities or regions, which has made it difficult for people to move freely along Colombia’s roads. At the same time, in many towns, including coffee ones, many people have lost their jobs or cannot continue whatever activity they did before the crisis. Many of those have found work picking coffee in the farms adjacent to or part of their municipalities. The federation, together with local authorities and farmers, has helped create those job opportunities.

Author

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Argentina Project

The Argentina Project is the premier institution for policy-relevant research on politics and economics in Argentina. Read more

Explore More in Weekly Asado

Browse Weekly Asado

Dengue Haunts South America’s Summers

Lessons from Costa Rica’s Economic Transformation

Women and Latin America’s Digital Revolution