“Dear Radio Tirana,” the letter begins, “here in the Alps we can hear you well, and we are especially fond of your propaganda directed at the Italian Communist Party.” The letter is dated April 12, 1976 but its Italian authors are not named. After a final greeting “Viva Mao e Viva Stalin,” they have simply signed off “a group of true Communists.”[i]

Two months earlier, in Entroncamento, Portugal, someone has penned a letter to the same station. “Camaradas,” his note begins, “I am a worker (a porter) who listens regularly to your Portuguese-language broadcasts.” The letter then proceeds with complaints about the fate of Communism in Portugal, with questions about Albania’s foreign policy, about why Radio Tirana spoke so infrequently about Portugal, about sports, about whether a trip to the Balkans might be possible.[ii]

By March, in Arequipa, Peru, a thirty-year-old places the recipient’s address on a small envelope: Señor Director, Radio Tirana, Albania.

He is among early Peruvian intellectuals who have been drawn to Mao Zedong’s ideas. Having completed a thesis on the topic, he is on his way to becoming a professor within a few years. “Unfortunately, I have to tell you that it’s been over a year that I do not receive your broadcasts,” he writes, “I think that it might due to the interference of the imperialist Yankees or perhaps the Soviet social-imperialists.”[iii]

Once a modest station, Radio Tirana had become a global Communist voice by the 1970s, reaching Brazilian guerillas in Araguaia, teeny-tiny Maoist factions across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, far-flung dots scattered across oceans and seas. This turned the station into a kind “of superpower of its kind” as author Ardian Vehbiu has put it. Officials embraced this role, broadcasting in numerous languages—English, Arabic, French, Italian, Greek, Portuguese, German, Indonesian—and beaming anti-capitalist and anti-Soviet messages day after day.

I explain how this came to be in the recently published volume Internationalists in European History, edited by Jessica Reinisch and David Brydan. The story of how a fascist-era radio station went global has something to do with 1950s Soviet involvement and even more with 1960s Chinese technical assistance. It is an illustration of how the convergence of geopolitics and infrastructure can yield surprising outcomes. Authoritarian types with big egos used radio as a powerful communication tool; inadvertently they also made room for listeners to come into contact with foreigners far away from them.

Broadcasting has left archival traces across national borders, but here I wish to highlight in particular unofficial accounts. Beyond institutional histories, radio is an invitation to capture the accidental and the human in encounters. Memoirs by radio veterans are rich sources. Then there are thousands of letters sent to Tirana, like those written in 1976 from Italians, Portuguese, and Peruvian listeners.

In 1979, 8,348 of these came from 99 countries, including 2,092 from West Germany, 872 from Italy, 573 from Britain, and hundreds more from Spain, Finland, France, Sweden, Colombia, and Japan. By then, Albanian-Chinese relations had tumbled, and many aging Western Maoists had moved on. One can trace this political history, as well as the confusion and despair it caused, in personal letters sent throughout the 1970s.

Such sources provide insights into the paradoxes of an era. While foreigners around the world tuned into Radio Tirana’s foreign language broadcasts, remote Albanian inhabitants hardly had access to their own national station. Tirana cultivated radio lovers around the world, but the regime punished domestic radio amateurs for coming up with ingenuous ways to access off-limits Western signals (and eventually Italian TV).

Letters also do not fit neatly into ideological containers. A majority of those who wrote were not necessarily drawn to the on-air propaganda. They were radio amateurs, tracking down obscure signals, seeking to communicate with mysterious voices on other side of the receiver. This kind of radio infatuation long predated the Cold War.

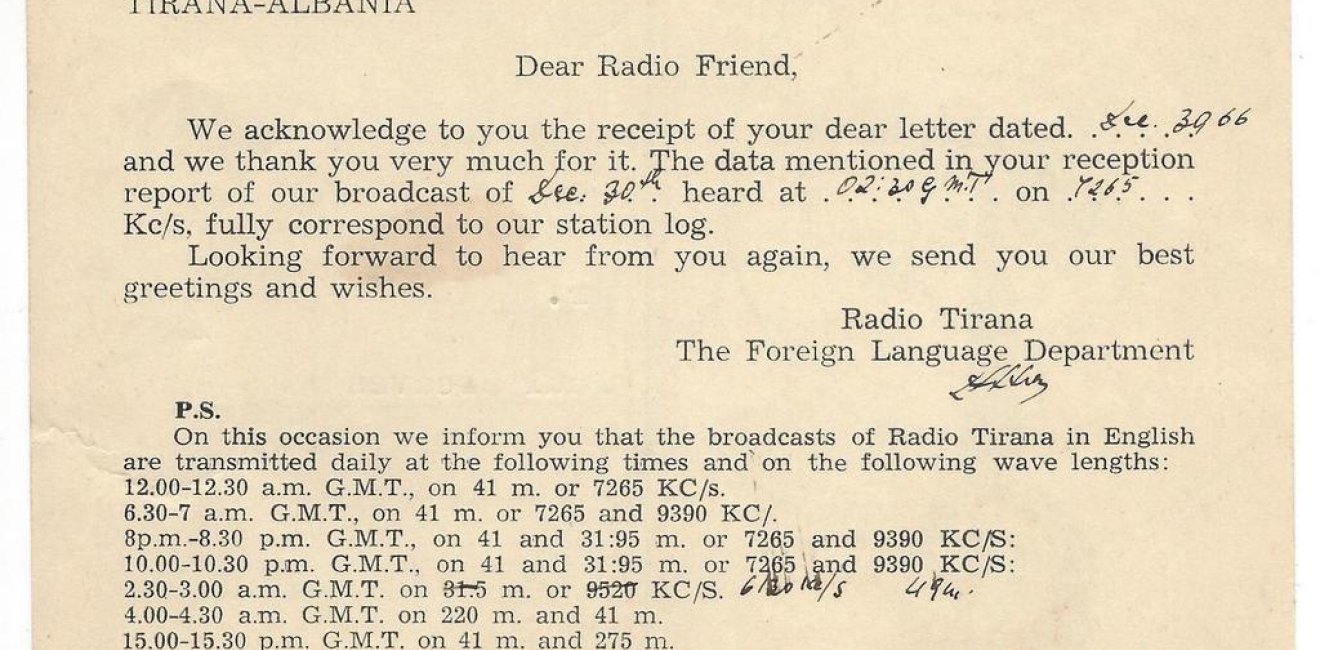

In their postcards and handwritten signal reports—some of which are still traded and purchased online—they marked down the time and frequency of broadcasts, the clarity of the sound, and any interferences. Such technical details would come in the mail, by the mid-70s, from Finland, Britain, Czechoslovakia, Iran (“an interference from an unidentified radio station broadcasting in Arabic”), from Hollywood, Minnesota, Kuwait, Australia, all the way from Japan.

Most of the senders probably did not care all that much about the content of Tirana’s tirades. Nevertheless, they wanted the station to send something back to them: a signal that it had received their message; a QSL card, or some other form of acknowledgment; a flag to add to their collection at home. Many of the listeners got their wish.

Some writers reported hearing merely noise. But noise was also identified, measured in time and space, patiently described, carefully documented. Proof of noise was committed to writing, folded inside envelopes adorned with stamps bearing portraits of philosophers, writers, scientists, or Queen Elizabeth II, then sent on its way to the Balkans. There, someone opened the envelopes, translated the letters, distilled the texts for the benefit of higher-ups, archived the mail. Noise has its history, too.[iv]

Some of the radio lovers were leftists trying to make sense of a desperately fractured—and still fracturing—Communist order. Geopolitical disunity revealed itself in the form of socialist cacophony. One listener from Manizales in Colombia reported difficulties catching Radio Tirana in April of 1978. Sure, Tirana broadcast in Spanish to Spain at 6:30 in the morning, but that was after midnight in Colombia. Later broadcasts were nearly impossible to tune into.

It turned out that Moscow could be heard on the same frequencies, so that in Manizales one was confronted with “a strange blend of voices where Radio Moscow’s Spanish-language lies are mixed up with the beloved frequencies of Socialist Albania.”[v] Two kinds of Spanish battled it out on their way to South America: One offered the Soviet version of the day’s events; the other the Albanian. Tirana tried to speak in the world’s languages, and languages often got entangled in the process.

Marxist-Leninists in Guadeloupe reported interferences from East German radio. An Italian listener tuned into the French broadcast because the Italian channel was blocked. BBC kept showing up as a hindrance, although BBC had long given up on the Albanian language. Moreover, Tirana kept occupying frequencies that were not allocated to it, causing grief in international broadcasting meetings. Scandinavian writers complained about the quality of English-language broadcasting, but the sound of Tirana’s English often traveled where it wanted—not necessarily where Tirana had intended it.

What happened to the technical data sent by mail? Herbert in Hamburg wrote in 1974 that the broadcasts were noisy. Officials took note of his complaint and sent it along to the postal service, which referred it to a local station so that the issue could be fixed. Other examples of this kind of transmission can be located in archives. This is notable because there were hardly any areas where a person in Western Europe could have technical influence inside 1970s Albania.

When the noise finally died down, Tirana’s voice could be decoded for geopolitical clues into what Beijing was up to after Mao’s death in 1976. One listener in Nigeria wrote a letter in March 1978 pointing out that the Chinese were no longer paying much attention to Iranian revolutionaries. What was going on? “Is there any change in the ideological position of the Chinese?””[vi] It took a month for the letter to get from Ganye, Nigeria, to Tirana.

In the meantime, Polish listeners had gotten used to broadcasts shaped in large part by Kazimierz Mijal, the pro-China figure who had parted ways with the leadership of the Polish United Workers’ Party. Scorned as a dogmatic, he ended up in Albania in 1966 thanks to a fake passport. There, he set up an alternative Polish Communist Party and declared himself interim party boss. Along with monitoring the airwaves, Warsaw kept an eye on his trip to China in 1975, as did the Soviets.

Letters from listeners are infused with big and small problems, from complaints about accents to expressions of fear and rage about arms sales, from hobby talk to puzzlement over China’s changing position in the world. A river of resentment runs through letters arriving from Italy during the anni di piombo—central targets were the Communists of Enrico Berlinguer and especially their political compromise. Some of the Italian writers had served in Albania during Mussolini’s years; theirs are letters that merge the genre of autobiography with views on current affairs in the space of a single handwritten page.

Quirks abound in the story of Maoism’s international footprint, as Julia Lovell’s global study superbly reveals.[vii] One Englishman comrade wrote to Radio Tirana from a “Enver Hoxha Farm” apparently set up in the picturesque village Flash in the Quarnford parish, Buxton. China’s post-Mao turn, he wrote, had left him embarrassed. “This action has made myself and my wife look fools after we had told many people here of Marxism in China and now we believe they are to buy arms etc. from the British Tories.”[viii]

As Sino-Albanian friendship disintegrated, a listener from Wrocław described life in Poland: the scarcity of consumer products; prices going up; the fact that young Polish couples could hardly obtain an apartment.[ix] After crossing heavily armed borders that autumn, the letter finally arrived at its destination—in Albania, where misery was even more profound and where it was about to get worse.

[i] “Caro Radio Tirana,” 12 April 1976, Arkivi Qendror Shtetëror (Central State Archives, Tirana, Albania, AQSH), F. 509, V. 1976, Dos. 27, Fl. 16-17.

[ii] “Camaradas,” 12 February 1976, AQSH, F. 509, V. 1976, Dos. 27, Fl. 2.

[iii] “Muy apreciado camarada,” 28 March 1976, AQSH, F. 509, V. 1976, Dos. 27, Fl. 13-14.

[iv] István Rév, “Just Noise? Impact of Radio Free Europe in Hungary,” in Cold War Broadcasting: Impact on the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, eds. A. Ross Johnson and R. Eugene Parta (Budapest, 2010), pp. 239-58.

[v] “Queridos compañeros,” 6 April 1978, AQSH, F. 509, V. 1978, Dos. 35, Fl. 1-3.

[vi] “Dear friends,” 13 March 1978, AQSH, F. 509, V. 1978, Dos. 35, Fl. 12.

[vii] Julia Lovell, Maoism: A Global History (New York: Knopf, 2019).

[viii] “Dear Albanian comrades,” n.d., AQSH, F. 509, V. 1978, Dos. 35, Fl. 32.

[ix] “Drodzy Towarzysze!” 23 October 1978, AQSH, F. 509, V. 1978, Dos. 35, Fl. 42.