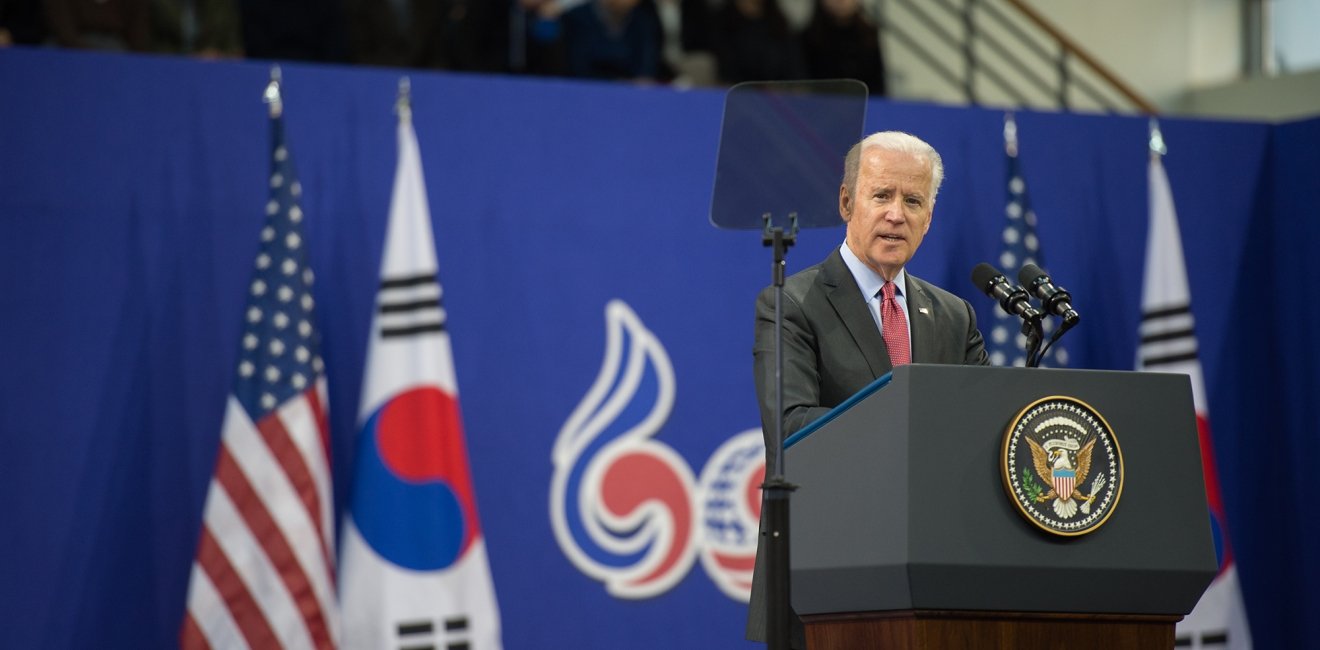

What Will a Biden Presidency Mean for the Korean Peninsula?

Wilson Center experts on the impact of the U.S. election on geopolitics in Korea

A blog of the Indo-Pacific Program

Wilson Center experts on the impact of the U.S. election on geopolitics in Korea

Last week, a majority of Americans elected former Vice President Joseph “Joe” Biden to be their next president in 2021, auguring major shifts in everything from how the coronavirus pandemic is handled to approaches in foreign policy.

After four dramatic years under President Donald Trump, Korea policy is bound to take a turn.

As Koreans on both sides of the DMZ watch the election play out, Wilson Center scholars are weighing in on the election’s impact on the Korean Peninsula, including how a Biden Administration may move to rein in North Korea’s nuclear ambitions, navigate a rising China, and restore fraying alliances.

By Jean H. Lee, Director, Hyundai Motor-Korea Foundation Center for Korean History and Public Policy at the Wilson Center

There’s no doubt that Kim Jong Un would have preferred a second Trump presidency. Kim has taken advantage of President Trump’s maverick style of diplomacy and the opening that Trump’s impulsiveness and craving for attention and drama have provided. Kim saw an opportunity to secure legitimacy at home and abroad, and spotted the potential to fundamentally change Pyongyang’s relationship with Washington by forcing the United States to acknowledge North Korea as a nuclear weapons state.

Things didn’t quite work out as Kim had hoped. Despite their “special” friendship, nuclear negotiations with Trump fell apart in February 2019, with no movement since then. However, since he already has invested so much in his unusual relationship with President Trump, Kim would prefer to stick to this process than start again with President-elect Biden, who will be less inclined to impromptu photo op summits.

In fact, North Korea has significantly expanded its arsenal during President Trump’s four years in office.

Unfortunately, President Trump’s approach has left us in a far more dangerous place with North Korea’s nuclear weapons than four years ago, and North Korea will be an even more formidable policy challenge in 2021. While Trump’s outreach was historic, it has not succeeded in any reduction of the nuclear threat that North Korea poses. In fact, North Korea has significantly expanded its arsenal during President Trump’s four years in office.

Like the rest of us, Kim Jong Un has been watching and waiting. He has been using the time to focus on domestic issues, and has quietly been ordering improvements to his weapons arsenal. He will be convening a party congress in January that should give us a sign of what policy direction he intends to take.

We’ll also be watching to see how quickly the Biden Administration lays out its foreign policy priorities. At the outset, the Biden Administration will likely be consumed by domestic issues, including flattening the curve on the pandemic and resuscitating the economy.

However, if North Korea doesn’t figure in President-elect Biden’s list of foreign policy priorities quickly, Kim may turn back to the tried and tested pattern of behavior of waging a major provocation to get back on Washington’s radar. President-elect Biden’s tough talk on North Korea may even give Kim further justification to carry out more weapons tests.

But in some ways, I think the North Koreans may also be relieved by the return to traditional diplomacy that President-elect Biden has promised after all the drama and disappointments of President Trump’s approach.

The question is whether the Biden Administration will be able to learn from past mistakes, move forward from where things left off, and find the right equation to resolve a nuclear situation that has become exponentially more complicated since President Trump took office.

Biden has not ruled out meeting Kim; in the last presidential debate, he said he would be willing to meet with Kim “on the condition he would agree he would be drawing down his nuclear capacity, to get the Korean Peninsula to be a nuclear-free zone.” The North Koreans’ ears should have perked up at the words “drawing down,” and the opportunity that may present for negotiation.

We can expect the Biden Administration to be more conscientious about coordinating and consulting with North Korea’s neighbors, including South Korea and perhaps even China.

What we can expect is that President-elect Biden will be listening to his advisers as well as to allies in the region. We can expect the Biden Administration to be more conscientious about coordinating and consulting with North Korea’s neighbors, including South Korea and perhaps even China.

Regional or international unity will make it harder for Kim to employ the tactic of sowing division among his neighbors. More coordination and communication are always better than less when it comes to diplomacy. Multilateralism is a far more sustainable strategy for securing stability on the Korean Peninsula, and we can look forward to a Biden Administration taking steps to repair relationships and to restore faith in the United States’ leadership.

By Katie Stallard, Wilson Center Global Fellow

Undoubtedly Kim Jong Un would have preferred another four years of Donald Trump and the chance of a deal that would ease sanctions without surrendering too much of his precious nuclear program. A Biden presidency augurs an end to the declarations of love and the photo opportunities and a return to a more conventional, disciplined approach, with the new administration expected to work more closely with regional allies and demand meaningful concessions before further leader-level talks.

Biden will inherit a more dangerous North Korea. Despite President Trump’s previous claims that there was “no longer a Nuclear Threat from North Korea” and he had “largely solved” the problem, the threat from Pyongyang has only increased since he came to power. During Trump’s time in office Kim Jong Un has advanced his nuclear and missile programs and broken out of his diplomatic isolation, strengthening ties with China and Russia and securing three meetings with a sitting US president, a feat neither his father nor his grandfather achieved. Deteriorating US-China relations have also decreased the incentive for Beijing to continue maintaining maximum pressure on Pyongyang.

However, by engaging directly with Kim Jong Un, Donald Trump has reduced the stigma for Biden to do so, who could otherwise have been accused of weakness and pandering to a dictator had a Republican president not met the North Korean leader first.

And while the broader relationship with the United States continues to decline, China may still be seeking opportunities for cooperation with the incoming administration, which could include North Korea. Beijing would certainly not welcome a winter of new missile or nuclear tests from Pyongyang - its priorities on the Korean peninsula remain avoiding conflict and regime collapse and the Communist Party leadership will not want to see any action from either side that might destabilize the region.

Kim Jong Un also faces his own domestic pressures. He has already acknowledged his failure to improve living conditions, tearfully apologizing to his citizens during a recent speech, with his economy strained by crippling sanctions and the coronavirus pandemic. He must now confront the prospect of a return to something like the Obama-era policy of strategic patience under a Biden presidency, which would leave the current sanctions regime in place and return Pyongyang to the diplomatic deep freeze, further thwarting his promises of economic development.

If the past is any guide, the North Korean leader will be considering a return to his previous tactics with a series of provocative nuclear and missile tests designed to raise tensions and elicit Washington’s attention, while also advancing and demonstrating the regime’s capabilities, before seeking negotiations and concessions. The difficulty for Kim this time will be calibrating how to force the North Korean issue onto the incoming president’s already crowded agenda, for instance by flight-testing his new ICBM, without incurring further sanctions or alienating China and returning to his previous isolation.

By Seong-chang CHEONG, Wilson Center fellow

With President-elect Joe Biden, who prefers alliance-building over “America First” policy, conflicts over defense cost-sharing between South Korea and the United States can be expected to be resolved early and smoothly.

Biden has described the North Korean leader Kim Jong Un as a dictator, a tyrant, a butcher, and a bully. Seoul will not be able to help but worry that the issue of North Korea's denuclearization may be pushed back by Washington's other foreign policy priorities.

Currently, North Korean diplomats have little negotiating power on the denuclearization issue, so if Biden wants to make substantial progress on denuclearization, he will have to meet Kim Jong Un in person and push for a significant deal.

At the same time, it is necessary to reach a comprehensive and concrete agreement on North Korea's denuclearization measures and [implement] the international community's corresponding measures--such as the normalization of US-North Korea relations and easing sanctions on the North--through a four-party summit involving the US, China, North Korea, and South Korea rather than a bilateral summit between the US and North Korea, a strategy which has failed to produce substantial results.

On Nov. 5, 2020, the Hyundai Motor-Korea Foundation for Korean History and Public Policy partnered with the KF-VUB Korea Chair in Brussels, Belgium, to organize a panel that was broadcast at the 2020 Jeju Forum for Peace and Prosperity on “The Korean Peninsula after the U.S. Election.”

Jean H. Lee was joined by Amb. Joseph Yun of the U.S. Institute of Peace; Dr. Kim Joonhyung, chancellor of the Korea National Diplomatic Academy of South Korea, and political analyst Dr. Kim Jiyoon. The discussion was moderated by Dr. Ramon Pacheco Pardo, the KF-VUB Korea Chair at the Institute for European Studies.

Watch the full webcast and read our event recap for highlights.

The Indo-Pacific Program promotes policy debate and intellectual discussions on US interests in the Asia-Pacific as well as political, economic, security, and social issues relating to the world’s most populous and economically dynamic region. Read more

The Center for Korean History and Public Policy was established in 2015 with the generous support of the Hyundai Motor Company and the Korea Foundation to provide a coherent, long-term platform for improving historical understanding of Korea and informing the public policy debate on the Korean peninsula in the United States and beyond. Read more