Kennan Cable No. 52: In Russia’s Shadow: China’s Rising Security Presence in Central Asia

On April 2, a plane carrying 500 kilos of testing equipment and PPE from China landed in Almaty.[1] A similar flight landed in Tashkent on March 30 and a team of 10 medical specialists from China arrived in Kyrgyzstan on April 21.[2] Not to be outdone by China’s “virus diplomacy,” Russia has donated 17,000 test kits to Kyrgyzstan[3] and 2,000 to Tajikistan.[4] These latest moves in response to COVID-19 are part of an ongoing struggle between Russia and China over influence in Central Asia.

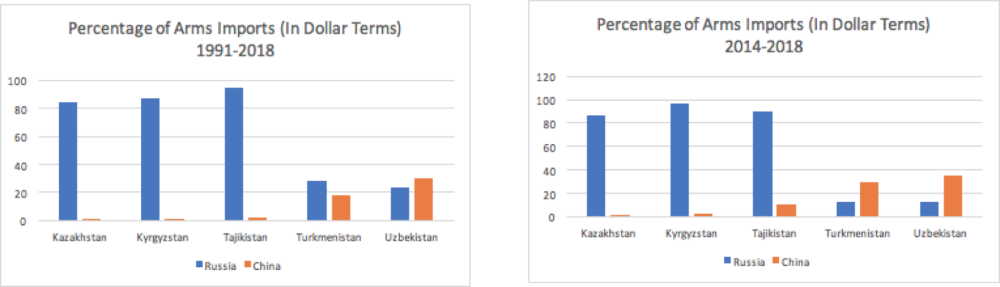

Central Asia is undergoing a significant geopolitical transition as Russia and China each work to strengthen their influence in the region. While Moscow’s economic dominance recedes in favor of Beijing, dropping from 80 percent of the region’s total trade in the 1990s ($110 billion) to just two-thirds that of Beijing’s today ($18.6 billion), it nevertheless remains the dominant security guarantor in the region.[5] Russia has accounted for 62 percent of the regional arms market over the past five years and maintains substantial military infrastructure in three out of five of the republics.[6] Moscow has also rapidly expanded its security drills and training in strategic Tajik border regions, and it launched its first lethal strike on Afghanistan since 1989 from Tajikistan in 2018.

Yet China is making significant inroads in the security sector. It has provided 18 percent of the region’s arms over the past five years, a significant increase from the 1.5 percent of Central Asian arms imports that it provided between 2010 and 2014. In 2016, China constructed its first military facilities in the region, high in Tajikistan’s Pamir Mountains, and in recent years, it has begun projecting the operational capabilities of its paramilitary units into the region.[7] While Moscow retains a strategic edge over Beijing, the gap is closing, and, if trends continue, Moscow may find its influence undermined in the coming decade.

China Enters the Arms Market

China is a relative newcomer to the global arms market, establishing itself as a net exporter only within the last decade.[8] Russia has supplied $36.3 billion of arms to China since 1991, over three-quarters of China arms imports.[9] But that number has decreased, from $21 billion in the first decade of the 21st century to $8 billion in the second decade, as China has developed its own armaments industry. From 2008 to 2018, China exported some $15.7 billion worth of weapons around the world, becoming the fifth largest global arms supplier. This is largely due to technical advances within Beijing’s armed forces. China’s military spending has surged since 1988, from $21 billion to $250 billion in 2018, although with PPP (purchasing power parity) factored in, this figure rises to over $600 billion, a large chunk of which goes to research and development.[10] Much like Russia, a large share of China’s weapons transfers to Central Asia are labelled donations, sidestepping 2002 legislation that places limits on Chinese arms exports.[11]

Since 2000, according to the SIPRI Arms Database, China has exported $444 million worth of arms to Central Asia, with 97 percent of those sales occurring after 2014. SIPRI’s dataset is somewhat limited, however, missing key large-scale transfers that push China’s total exports to the region above $717 million (see Figure 1). Until 2014, Beijing arms transfers were modest, including $17.2 million in aid to Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, $4.5 million to Kazakhstan, and a 2007 loan of $3 million to Turkmenistan for the procurement of precision equipment.

Since 2014, China has ramped up arms transfers to the region. In 2015, Kazakhstan received 30 Jiefang J6 heavy-duty trucks and 30 large-load trailers worth $3.2 million as a gift from the People’s Republic.[12] In September 2018, Kazakhstan bought eight Chinese Y-8 transport airplanes, modelled on the Russian Antonov An-12.[13] This activity has also led to a diminishing lead for Russia in the supply of advanced weapons systems. For example, Turkmenistan purchased a QW-2 Vanguard 2 portable surface-to-air missile, modelled on Russia’s 9K38 Igla 2018, from the Chinese military technology company CATIC.[14] In November 2019, Uzbekistan’s Air Defense Force successfully tested China’s FD-2000 medium-range air-defense system on a target drone.[15] The China Ordnance Industry Group Corporation Limited donated VP11 patrol vehicles to Tajikistan in 2018.[16]

China is also dominating in sectors where Russian technology continues to lag.[17] In recent years Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan have all received armed drones from China, a strategic global market once the preserve of the U.S. and Israel.[18] The most well-known and used Chinese drones are the CH-3, CH-4, CH-5, and the Wing Loong.[19]Kazakhstan (2015) and Uzbekistan (2014) have purchased a number of Wing Loongs, and Turkmenistan (2016) operates the CH-3.[20]

In addition to purchases and direct donations, Central Asia also procures Chinese weapons systems by bartering its substantial petrochemical resources.[21] Both Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan used gas to obtain their HQ-9 missile defense systems from Beijing. But this agreement broke down. By January 2019, China had placed Turkmenistan on a military blacklist, ceasing all military exports to the country after Ashgabat struggled to pay back a loan issued by Beijing after its gas production plummeted.[22] In the wake of COVID-19, China’s slowing energy demand and falling gas prices may lead to loan repayment issues in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, the other major suppliers for China, with similar implications for their arms industries.[23]

Russia, Still Dominant

In spite of recent Chinese gains, Russia remains the dominant external security partner for the region and largest supplier of arms, as Figure 1 shows. Russian arms transfers to the region have grown dramatically over the past decade. In 1988, Soviet military expenditures stood at $350 billion but by 1992, Russia’s military budget had dropped to $60 billion, and by 1998, it reached a low of $19 billion.[24] The budget has grown substantially since Vladimir Putin rose to prominence, reaching $47 billion in recent years, or $150 billion if you use PPP.[25] With the increasing budget, arms exports have increased, averaging $3 billion in the 1990s and doubling to an average of $6 billion per year since 2000. According to the SIPRI Arms Transfers Database and additional data collected by the authors, Russia has sold $3.8 billion worth of arms to Central Asia since 1991, with the lion’s share, $2.3 billion, going to Kazakhstan. Russia has supplied over 80 percent of the imported arms to Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, as shown in Figure 2 below. Arms sales have steadily grown, with three-quarters of Russian exports to Central Asia being sold since 2010.[26]

Figure 1: Arms Sales to Central Asia (1991–2019)

Figure 2: Percentage of Arms Imports to Central Asia from Russia and China

In 2012, the Russian military promised a $1.1 billion aid package to improve Kyrgyzstan’s military.[27] Since then, Russia and Kyrgyzstan have signed several agreements under which up to $200 million worth of secondhand Russian weapons and gear will be supplied free of charge, including air transport, attack helicopters, surface-to-air missiles, trucks, and other hardware. Tajikistan’s military, according to defense analyst Vladmir Mukhin, “today represents a small outpost of the Russian army. It is completely equipped with Russian arms and even has the same organizational structure.”[28] In 2017, Tajikistan received $122 million worth of Russian hardware and in 2019, Moscow pledged to invest a further $200 million toward modernizing the Tajik army up to 2025.[29]

As noted above, Kazakhstan is the largest consumer of Russian arms in the region. In 2013, the two countries formed a unitary regional air-defense system, with Kazakhstan receiving the S-300PS air-defense system free of charge. Most recently, Russia supplied the Kazakh navy with two minesweepers, four Mi-35M attack helicopters, and 12 Su-30SM fighter-bombers. Kazakhstan has also developed its own defense industry, in 2019 signing an agreement with Russia to assemble Mi-8AMT and Mi-171 helicopters in Kazakhstan.[30]

Uzbekistan, the most populous country in Central Asia, had long tried to distance itself from Russia, suspending its membership in the Russian-led CSTO (Collective Security Treaty Organization) from 1999 to 2006 and then leaving it entirely in 2012. Uzbekistan is the only country in Central Asia to have spent more on weapons from China than from Russia (see Figure 2). Since the death of Islam Karimov in 2016, however, Uzbekistan has changed course and Russia has played a prominent role in the latter stages of its rearmament program (launched in 2012). That year, the two sides signed an agreement on military technical cooperation which allows Uzbekistan to buy Russian arms at the domestic prices paid by the Russian military. A new defense doctrine adopted in 2017 outlined three priorities: rearming the military with modern weapons, launching a local military industry, and reorganizing the armed forces. By 2018, its military spending had swelled to $1.4 billion, with Russia and Uzbekistan signing deals on 12 Mi8 attack helicopters, armored personnel vehicles, and Su-30SM fighter jets.[31]

Like Uzbekistan, neutral Turkmenistan has attempted to decouple its security from Russia. While Russia has sold more weapons to Turkmenistan than China has—$370 million in sales compared with $234 million—it is still not Turkmenistan’s largest arms supplier. Turkey has supplied $407 million in sales to Turkmenistan, according to the SIPRI database, including patrol ships and armored personnel carriers.[32] But as militants have seized Afghanistan’s districts near the 744-kilometer Turkmen-Afghan border in recent years, cooperation with Russia, whose border guards were stationed in Turkmenistan until 1999, has intensified.

Figure 3: Large Arms Sales to Central Asia since 2012

Importer

Exporter

Year

Equipment

Companies

Type

Value

Kyrgyzstan

Russia

2012–

2018

2 An-26, 4 Mi-24V, Mi-8MTV helicopters, two batteries of Pechora-2M SAM, BTR-70M

Antonov, Russian Aircraft Corporation, Almaz Antey

Transport plane, attack helicopter, helicopter, missile, armored personnel carrier

$125 million

Kazakhstan

Russia

2014

32 Su-30SM

Sukhoi

Fighter jet

$805 million

Turkmenistan

China

2016

HQ-9, HQ12

China Precision Machinery Import-Export Corporation

Missile sytem

$230 million

Tajikistan

Russia

2017

T-72B1, BTR-80 and BTR-70, BMP-2, Mi-24 and Mi-8, D-30

Uralvagonzavod, Arzamas, Kurganmashzavod,Russian Aircraft Corporation, PJSC «Plant № 9»

Tank, APC, helicopter, howitzer

$122 million

Kazakhstan

China

2018

8 Y-8F-200W

Shaanxi Aircraft Corporation

Transport plane

$296 million

Uzbekistan

Russia

2018

12 Mi-35M

Russian Aircraft Corporation

Attack helicopter

$432 million

Uzbekistan

China

2019

HQ-9 (FD-2000)

China Precision Machinery Import-Export Corporation

Missile system

$103 million

Tajikistan

Russia

2019

S300

Almaz Antey

Missile system

$150 million

Military Engagement: Competing for Influence in Central Asia

Russia and China are both concerned about potential spillovers from Afghanistan and the potential for instability in the region. Both countries share a desire to reduce U.S. influence in the region and are conservative, supporting incumbent regimes. Yet they are both vying for influence in the region.

Russia has the competitive advantage. It maintains significant strategic facilities across the region, including 7,000 troops stationed in Tajikistan, an airbase in Kyrgyzstan, a cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, and various other radar stations and testing sites. China is a relatively new actor in this regard, creating its first strategic holding only in 2016, with facilities in Tajikistan’s mountainous Gorno-Badakhshan province, 14 kilometers from the Afghan border. According to satellite reconnaissance, the base is equipped with heliports and enough barracks to house a battalion, with support from armored vehicles.

Russia and China increasingly view training programs for local officers as a way to expand their regional influence. Kazakhstan accounts for about one-third of all foreign officers trained in Russian military academies, with the result that more than half of the Kazakhstani army is now trained at least partly in Russia.[33] Moscow recently renewed its training program for Uzbek officers at Russian military institutions, which had been disrupted in 2012 as Tashkent left the CSTO, although the number of officers enrolled in the program, 20 per year, is rather low.[34] Russian military officials claim that “more than 1,500 junior specialists” from Tajikistan are now studying in Russian military schools, where they are learning to operate the new weapons systems stationed there, such as the S-300 missile system. As of 2014, 70 percent of officers in the country’s special operations forces graduated from Russian military institutes. These numbers are significant, given that the entire Tajik military, including paramilitary forces, numbers only 16,300 troops.

China was slow to enter this area for cooperation in the region. Between 1990 and 2005, only 15 Kazakh officers were sent to China for training.[35] While China has trained more Central Asian military personnel in recent years, it still lags behind Russia. For example, 65 members of the Kazakh military have taken courses in Chinese institutions between 2003 and 2009. Thirty Kyrgyz officers also received training in China.[36] China’s People’s Armed Police (PAP) paramilitary unit also runs limited training schemes for local officials, and dozens of People’s Liberation Army (PLA) academies train foreign officers in both short-term and long-term programs with an unspecified number of Central Asian participants.

China has also been running a number of programs across the region in recent years. In 2016, it helped establish a new department at Kazakhstan’s University of Defense and that same year the Chinese Criminal Police Academy cooperated with Kazakhstan for a series of anti-drug business training courses.[37] Uzbekistan’s Academy of the Ministry of Interior Affairs (MIA) and the People’s Public Security University of China, run by China’s powerful Ministry of Public Security, have been official partners since May 2017.[38] Since then, China has hosted 213 Uzbek MIA employees over the course of 38 meetings for security briefings on counterterrorism and drug trafficking.

China also conducts training through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). In 2014, the Ministry of Public Security (MPS) founded the China National Institute for SCO International Exchange and Judicial Cooperation in Shanghai, an institute created with the purpose of training SCO senior officials on topics such as counterterrorism and transnational crime. The center claims to have trained some 300 officials from SCO member states from 2014 to 2018, an average of 75 per year.[39] The center announced in June 2018 that it plans to train 2,000 officials from all SCO countries by June 2021.

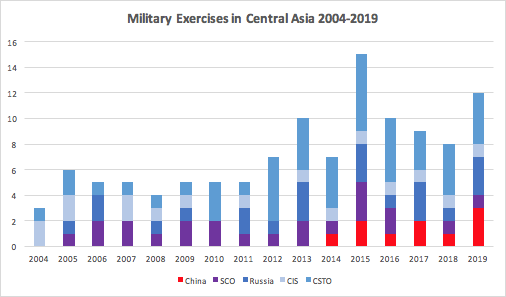

Finally, there is the issue of joint-training initiatives to improve the interoperability of forces in the region. Both Russia and China rely on a mix of bilateral and multilateral initiatives through their respective regional organizations: the SCO in the case of China and the CSTO and CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States) in the case of Russia. As Figure 4 indicates, military exercises have become more frequent in the region, peaking at 15 in 2015. Russia still conducts most of its exercises through the CSTO, with 45 of the 115 exercises that have taken place since 2004. Russia has also run bilateral exercises, usually through its military facilities in Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan. In 2017, Russia held its first exercise with Uzbekistan in 12 years at the Forish Range in Jizzakh, the site of the two countries' only previous bilateral exercise in 2005.[40]

Figure 4: Military Exercises in Central Asia (2004-2019)

China has gradually changed its approach to exercises in the region. At first, the exercises conducted within the framework of the SCO were bilateral. In 2002, the first joint exercises between China and Kyrgyzstan were held—China’s first-ever bilateral exercise.[41] It was not until August 2003, in eastern Kazakhstan and Xinjiang, that the first multilateral military exercises took place. All member states, except Uzbekistan, participated. In 2007, two joint military exercises were organized. The first, called “2007 Anti-Terror Issyk-Kul,” took place in late May on the shores of Lake Issyk-Kul and brought together SCO soldiers as well as officials from the CSTO and representatives of the security agencies and special services of each member state.

In 2015, General Secretary Xi Jinping made a speech announcing that military diplomacy would be a critical element of China’s foreign policy.[42] According to official data from the following year, China conducted 277 military exercises and high-level meetings abroad, almost double the 131 such activities in 2003.[43] This growth in China’s training activities is also notable in Central Asia. China has conducted at least 10 bilateral exercises in the region since then. In 2015, Tajik and Chinese special operations forces conducted joint counterterrorism drills at a mountain training center outside Dushanbe, marking the first time the MPS special operations forces conducted training exercises overseas.

One important trend in recent years has been the launch of “Cooperation 2019,” a series of drills allowing China to enhance the interoperability of local paramilitary units with its own People’s Armed Police (PAP). Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan all took part in 2019, marking the first time their national guard units had trained with China on counterterrorism. Russia has cautiously eyed the activities of the PAP and in recent years has promoted its equivalent unit Rosgvardiya as an alternative partner for Tashkent. In October 2018, the Uzbek and Russian national guards signed a cooperation agreement, Rosgvardiya’s first in the region, with two delegations from Uzbekistan visiting Russia in 2019.[44]

Cracks in the Sino-Russian Alliance?

United by a common desire to restrict U.S. influence in their spheres of influence and support incumbent regimes, Russia and China have developed a relatively robust partnership, albeit an increasingly asymmetric one in favor of China. Yet this relationship could be tested in Central Asia if the trends identified in this Kennan Cable continue. For decades, Russia has positioned itself as the dominant security guarantor in Central Asia, but patterns indicate that as China continues to rise, so will its hard power interests in the region. While Russian influence and its role in Central Asian security are not declining, China is taking an increasingly active role, developing its own initiatives without Moscow. As we enter an era of growing great power competition, regions like Central Asia may see rising tensions as states compete for influence.

Nevertheless, while China appears to be competing with Russia in a number of areas in this part of the world, the Sino-Russian alliance is moving ahead stronger than ever before. In 2018, over 3,000 Chinese soldiers joined 25,000 troops in Russia’s Far East as part of its “Vostok 2018” military exercises.[45] Last July, the two countries conducted joint bomber-patrols over the Asia-Pacific for the first time.[46] This partnership has also taken root in Central Asia. At Beijing’s 2019 Belt and Road Forum, Russian President Vladimir Putin gave a speech arguing that China’s BRI project meshes perfectly with the goals of the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union.

Thus far, while China’s arms sales to the region have increased dramatically since 2014, Russia’s share of the total for Central Asian arms imports has remained constant, at around 60 percent over the past 10 years. Instead, China has been taking market share from Turkey, Ukraine, Spain, France, and others. But if the trend continues, China may start to eat into Russia’s share, which could cause friction.

In the short term, Russia and China share core strategies in the region and they are unlikely to react to one another’s movements with hostility. But their relationship looks set to be tested in the medium term as China’s security role in the region becomes stronger.

[1] “Kazakhstan Receives Humanitarian Aid from China to Combat COVID-19,” Toppress.kz, April 2, 2020, https://toppress.kz/article/60407/kazakhstan-receives-humanitarian-aid-from-china-to-combat-covid-19

[2] “Chinese Medical Team Arrives in Kyrgyzstan to Fight COVID-19,” Xinhua, April 21, 2020, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-04/21/c_138993535.htm

[3] “Russian, Kyrgyz PM Discuss Delivery of COVID-19 Test Kits to Kyrgyzstan,” Tass, March 25, 2020, https://tass.com/economy/1135259

[4] “Россия направила Таджикистану средства диагностики коронавируса [Russia Sends COVID-19 Testing Kits to Tajikistan],” RFE/RL, February 4, 2020, https://rus.ozodi.org/a/30416732.html

[5] Edward Lemon and Bradley Jardine, “How is Russia Responding to China’s Creeping Security Presence in Tajikistan?” Russian Analytical Digest 248 (March 6, 2020): 6–8, https://css.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/pdfs/RAD_248.pdf

[6] This is based on the SIPRI Arms Transfer database, augmented with other deals that are not reflected in the SIPRI figures.

[7] Joel Wuthnow, China’s Other Army: The People’s Armed Police in an Era of Reform (Washington, DC: National Defense University, April 2019), https://inss.ndu.edu/Portals/82/China%20SP%2014%20Final%20for%20Web.pdf

[8] “How Dominant is China in the Global Arms Trade?” China Power, August 2018, https://chinapower.csis.org/china-global-arms-trade/

[9] “SIPRI Arms Transfer Database,” http://armstrade.sipri.org/armstrade/html/export_values.php

[10] “China’s Defense Spending is Larger than it Looks,” Defense One, March 25, 2020, https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2020/03/chinas-defense-spending-larger-it-looks/164060/

[11] Ministry of Commerce, People’s Republic of China (website), “Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Export Control of Missiles and Missile-Related Items and Technologies,” August 22, 2002, http://english.mofcom.gov.cn/article/lawsdata/chineselaw/200211/20021100053898.shtml

[12] Temur Umarov, “China Looms Large in Central Asia,” Carnegie Moscow Center (website), March 30, 2020, https://carnegie.ru/commentary/81402

[13] Zhōngguó guóchǎn yùnshūjī jíbài měi é chǎnpǐn: Chūkǒu zhōng yà ràng wài méi fànsuān [Chinese Domestic Transport Aircraft Beat U.S. and Russian Products in Central Asia],” 新浪军事, October 11, 2018, https://mil.news.sina.com.cn/jssd/2018-10-11/doc-ihmhafiq9908390.shtml

[14] “Chinese QW2 MANPADS Missile in Service with Turkmenistan Army,” Army Recognition (website), January 12, 2018, https://www.armyrecognition.com/january_2018_global_defense_security_army_news_industry/chinese_qw-2_manpads_missile_in_service_with_turkmenistan_army.html

[15] Samuel Cranny-Evans, “Uzbekistan Conducts First FD-2000 Air-Defense Test,” Jane’s Defence (website), November 22, 2019, https://www.janes.com/article/92799/uzbekistan-conducts-first-fd-2000-air-defence-test

[16] “Tajikistan: New Military Vehicles for GKNB Border Troops,” Army Recognition (website), December 11, 2018, https://www.armyrecognition.com/december_2018_global_defense_security_army_news_industry/tajikistan_new_military_vehicles_for_gknb_border_troops.html

[17] David Axe, “Russia Has Just Created the World’s Least Stealthy Stealth Drone,” National Interest, March 7, 2020, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/russia-has-just-created-worlds-most-non-stealthy-stealth-drone-129817

[18] Henrik Paulsson, “Explaining the Proliferation of Chinese Drones,” The Diplomat, November 10, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/11/explaining-the-proliferation-of-chinas-drones/

[19] Ben Brimelow, “Chinese Drones May Soon Swarm the Market—and That Could be Very Bad for the U.S.,” Business Insider, November 16, 2017, https://www.businessinsider.com/chinese-drones-swarm-market-2017-11

[20] “Uzbekistan Purchases Military Drones from China,” Security Assistance Monitor, June 5, 2014, https://securityassistance.org/content/uzbekistan-purchases-military-drones-china

[21] “In-Depth: How China Became the World’s Third-Largest Supplier of Weapons Worldwide,” China Military Online, February 27, 2018, http://english.chinamil.com.cn/view/2018-02/27/content_7953754.htm

[22] “Zhōngguó de wǔqì hái bù bèi rènkě? Yǒuxiē guójiā yǐjīng bèi liè rù hēi míngdān [China's Weapons Have Not Yet Been Approved? Some Countries Have Been Blacklisted],” Sina Military, January 21, 2019, https://mil.sina.cn/sd/2019-01-21/detail-ihqfskcn9151073.d.html?cre=tianyi&mod=wpage&loc=15&r=32&rfunc=59&tj=none&tr=32

[23] Maximilian Hess, “Central Asia’s Force Majeure Fears: Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak on China’s Natural Gas Supply Demands,” Foreign Policy Research Institute (website), March 16, 2020, https://www.fpri.org/article/2020/03/central-asias-force-majeure-fears-impact-of-covid-19-outbreak-on-chinas-natural-gas-supply-demands/

[24] Siemon T. Wezeman, “China, Russia and the Shifting Landscape of Arms Sales” SIPRI (website), July 5, 2017, https://www.sipri.org/commentary/topical-backgrounder/2017/china-russia-and-shifting-landscape-arms-sales

[25] Ben Vogel, “Russia Sketches Out Spending Plans for 2020–2022,” Jane’s Defence (website), October 2, 2019, https://www.janes.com/article/91653/russia-sketches-out-spending-plans-for-2020-22

[26]SIPRI Arms Database, http://armstrade.sipri.org/armstrade/html/export_values.php

[27]Joshua Kucera, “Report: Russia Spending $1.3 Billion To Arm Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan,” Eurasianet, November 7, 2012, https://eurasianet.org/report-russia-spending-13-billion-to-arm-kyrgyzstan-tajikistan

[28]Paul Goble, “Tajik Military Increasingly Part of Russian Army in All but Name,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, Jamestown Foundation, June 6, 2019, https://jamestown.org/program/tajik-military-increasingly-part-of-russian-army-in-all-but-name/

[29]“Russia Hands over US$122 Million Worth of Weapons and Military Hardware to Tajikistan in Five Years,” Asia-Plus, May 29, 2019, https://asiaplustj.info/en/news/tajikistan/security/20190529/russian-hands-over-us122-million-worth-of-weapons-and-military-hardware-to-tajikistan-in-five-years

[30] “Вместе - сильнее: как Казахстан наращивает военную мощь” [Stronger Together: How Kazakhstan is Building up Its Military Power], Sputnik, February 20, 2020, https://tj.sputniknews.ru/columnists/20200220/1030750859/Kazahstan-voennaya-mosch.html

[31]“Как узбекская армия стала сильнейшей в Центральной Азии (I)” [How the Uzbek Army Became the Strongest in Central Asia], RITI Evrazia, May 18, 2018, https://www.ritmeurasia.org/news--2018-05-18--kak-uzbekskaja-armija-stala-silnejshej-v-centralnoj-azii-i-36509

[32]Joshua Kucera, “Turkmenistan's Navy Shows Off New French Missiles,” Eurasianet, January 31, 2017, https://eurasianet.org/turkmenistans-navy-shows-new-french-missiles

[33] Marlene Laruelle, Dylan Royce, and Serik Beyssembayev, “Untangling the Puzzle of ‘Russian Influence’ in Kazakhstan,” Eurasian Geography and Economics 60, no. 2 (2019): 211–243, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15387216.2019.1645033

[34] “Минобороны отбирает военнослужащих для обучения в российских вузах” [The Ministry of Defense Selects Military Personnel to Study at Russian Universities], Sputnik, June 6, 2017, https://uz.sputniknews.ru/society/20170606/5566271/Voennye-uchitsya-v-Rossii.html

[35] Sebastien Peyrouse, “Military Cooperation Between China and Central Asia: Breakthrough, Limits, and Prospects,” China Brief, Jamestown Foundation, March 5, 2010, https://jamestown.org/program/military-cooperation-between-china-and-central-asia-breakthrough-limits-and-prospects/

[36] “Военное сотрудничество между Китаем и Центральной Азией: прорыв, пределы и перспективы” [Military Cooperation Between China and Central Asia: A Breakthrough, Limits and Prospects], RFE/RL, April 20, 2010, https://rus.azattyq.org/a/central_asia_china_millitary_help/1986304.html

[37] “Cháng wànquán yǔ hāsàkè sītǎn guófáng bùzhǎng jǔ háng huìtán [Chang Wanquan Holds Talks with Kazakhstan’s Defense Minister],” China’s Ministry of Defense, June 7, 2016, http://www.mod.gov.cn/leaders/2016-06/07/content_4675251.htm

[38] Umida Hashimova, “Uzbekistan Looks to China for Police for Policing Experience,” The Diplomat, September 10, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/09/uzbekistan-looks-to-china-for-policing-experience/

[39] Nadège Rolland, ed., Securing the Belt and Road Initiative: China’s Evolving Military Engagement Along the Silk Roads (Washington, DC: National Bureau of Asian Research, September 2019), https://www.nbr.org/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/publications/sr80_securing_the_belt_and_road_sep2019.pdf

[40] John C. K. Daly, “Russia and Uzbekistan Hold First Joint Military Exercise in 12 Years, Plan Further Cooperation, Eurasia Daily Monitor, Jamestown Foundation, October 3, 2017, https://jamestown.org/program/russia-and-uzbekistan-hold-first-joint-military-exercise-in-12-years-plan-further-cooperation/

[41] Bates Gill and Matthew Oresman, China’s New Journey to the West: China’s Emergence in Central Asia and Implications for U.S. Interests (Washington, DC: CSIS, August 2003), 20, shorturl.at/luN09

[42] “Xíjìnpíng: Jìnyībù kāichuàng jūnshì wàijiāo xīn júmiàn [Xi Jinping: Further Opening Up a New Situation in Military Diplomacy],” CPCnews, January 29, 2015, http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2015/0129/c64094-26474947.html

[43] “How is China Bolstering its Military Diplomatic Relations?” ChinaPower (website), January 27, 2020, https://chinapower.csis.org/china-military-diplomacy/

[44] Umida Hashimova, “Uzbekistan Looks to China for Police for Policing Experience,” The Diplomat, September 10, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/09/uzbekistan-looks-to-china-for-policing-experience/

[45] “Why Russia and China’s Joint Military Exercises Should Worry the West,” The Economist, September 6, 2018, https://www.economist.com/leaders/2018/09/06/why-russia-and-chinas-joint-military-exercises-should-worry-the-west

[46] Andrew Osborn and Joyce Lee, “First Russian-Chinese Air Patrol in Asia-Pacific Draws Shots from South Korea,” Reuters, July 22, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-southkorea-russia-aircraft/first-russian-chinese-air-patrol-in-asia-pacific-draws-shots-from-south-korea-idUSKCN1UI072

Authors

Director of Research, Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs

President, Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs; Research Assistant Professor, The Bush School of Government and Public Service, Texas A&M University (Washington, D.C. Teaching Site)

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Wilson Center is proud of its historic connection to the Kennan Institute and looks forward to supporting its activities as an independent center of knowledge. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

The OSCE is a Good Value for America