Violent Crime Plagues Businesses in Mexico

Beyond the human tragedy wrought by violent crime, its detrimental effects on businesses and economies can also devastate communities. This expert take discusses these effects on businesses in Mexico.

Beyond the human tragedy wrought by violent crime, its detrimental effects on businesses and economies can also devastate communities. This expert take discusses these effects on businesses in Mexico.

Beyond the human tragedy wrought by violent crime, its detrimental effects on businesses and economies can also devastate communities. Businesses are shuttered, employees flee, investments and tourism dry up, and budgets are skewed towards providing greater security. And while it is difficult to calculate the exact economic cost resulting from violent crime and insecurity, the numbers are certainly high. In 2011, the World Bank’s World Development report specifically documented the manner in which organized crime, ranging from human trafficking to drug smuggling, directly threatens and impedes economic development, especially in Fragile and Conflict-Affected States (FCS). According to the report, “the Mexican Government estimates that crime and violence cost the country 1 percent of GDP from lost sales jobs, and investment in 2007 alone.” This is well before the spike in violent crime in 2010 and 2011. Moreover, when the indirect costs associated with crime and violence are considered, such as trauma and injuries, the costs are “staggering.”

Over the past nine years, Mexico has engaged in a very public battle with international criminal networks involved in illicit trafficking of all kinds; but, they have also faced ever-stronger local criminal networks devoted to extortion of individuals and businesses, kidnapping, and auto theft, among other illicit activities. Drivers of oil tankers are constantly targets of extortion and theft, and Insight Crime reported in February that the state owned oil company (PEMEX) “will cease transporting fully refined gasoline and diesel fuel through its pipelines”, in order to combat pervasive oil theft.

In January 2015, Kathryn Haahr, a specialist in international security threats and risk management, addressed the challenges and concerns facing Mexico’s oil industry at a Wilson Center conference. She also authored a case study for the Mexico Institute titled “Addressing the Concerns of the Oil Industry: Security Challenges in Northeastern Mexico and Government Responses.” In it she noted that “homicide, kidnapping, extortion, attacks on facilities, and organized public unrest challenge regional governance and have the potential to impact a number of stages of the oil and gas value chain.” Despite these challenges, Haahr also expressed optimism about the country’s energy reforms and its inclusion of a specific role for the Mexican military in protecting key oil installations in Veracruz and Tamaulipas. Unfortunately, with the recent embarrassing escape of drug kingpin, “El Chapo” Guzman, and the disappointing outcome in the first round of public sales of shares in Mexico’s oil sector, it appears that organized crime has once again exacted an economic cost on Mexico.

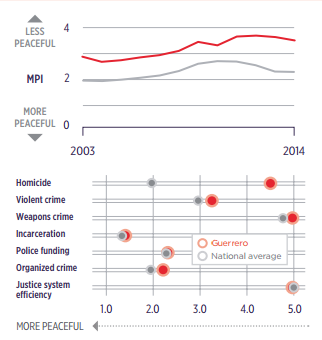

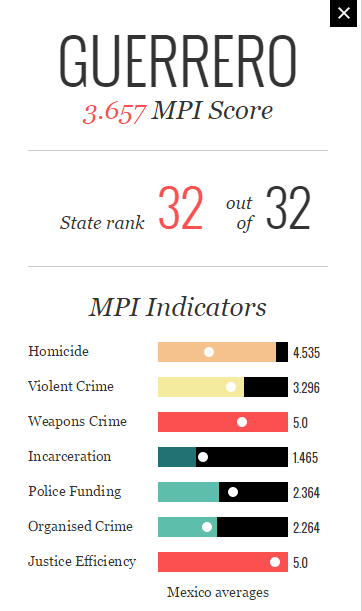

Similarly, in the deeply troubled state of Guerrero, criminal networks have also exacted a heavy toll on local economies and jobs. The 2015 Mexico Peace Index Report ranks Guerrero the least secure and most violent among Mexico’s 31 states and federal district. On June 24th a local Pepsi executive was kidnapped while driving on the highway. According to press accounts from Forbes and many others, this was not an isolated incident but one that “mirrors a string of other kidnappings and killings in the area.” Moreover, Coca-Cola recently decided to shutter its facility in the nearby town of Arcelia, “due to on-going security problems,” while Cemex has reportedly considered shutting its doors in the same area. Overall, Forbes reported that “10% of Iguala’s businesses have shuttered their doors,” according to Zacarías Rodríguez Cabrera, the Chairman of the Iguala chapter of Mexico’s National Chamber of Commerce, Service and Tourism (Canaco-Servytur). Thus, despite the overall decline in violent crime in Mexico in 2014, there are still major security concerns facing communities and businesses in several states such as Guerrero, the State of México, and Michoacán among others.

In Mexico and throughout Latin America the understandable response of the business community has often been to spend more to protect its employees, its facilities, and its investments. This has led to a burgeoning private security sector that in some cases, such as Guatemala and Honduras, has grown to twice and three-times the size of state police forces. Often times the public and business community support private security firms because they are justifiably distrustful of police forces that are weak, poorly trained and remunerated, and easily corrupted by criminal networks. Yet, abandoning the state to create a parallel system of security, which is mostly unregulated, can be tricky and result in many abuses while making reform of the state even harder. At times, private security can contribute to improved security for a business or its clients while the overall security situation worsens.

Not all Mexican businesses and economic elites have responded in this manner. Some have been a voice for reform in their communities. Several examples were documented in the Mexico’s Institute 2014 report, “Building Resilient Communities: Civic Responses to Crime and Violence.” It describes the contributions of businesses and professionals in Ciudad Juarez and Monterrey to improving public security generally, not just for their own private security. While businesses need to take measures to protect their employees and investments, this should be part of a broader approach that contributes to reform of state institutions and public security for all. Otherwise, the crisis of public confidence in local and national governments will only deepen.

The Mexico Institute seeks to improve understanding, communication, and cooperation between Mexico and the United States by promoting original research, encouraging public discussion, and proposing policy options for enhancing the bilateral relationship. A binational Advisory Board, chaired by Luis Téllez and Earl Anthony Wayne, oversees the work of the Mexico Institute. Read more