A blog of the Latin America Program

Contagion: Brazil’s COVID-19 Catastrophe Spills Over Borders

More than 90,000 Brazilians have died of the novel coronavirus, and there were more than 2.5 million confirmed cases as of July 30, including President Jair Bolsonaro. Testing and contract tracing have lagged, a consequence of turnover at the Ministry of Health, poor coordination and an absence of national leadership. Public concern is growing as the spread of the virus accelerates. Nonetheless, the Bolsonaro government continues to downplay the severity of the health crisis and push for faster economic reopening.

Brazil’s struggles have implications for its neighbors. Residents along the country’s porous 10,492-mile border are accustomed to easy and frequent crossings that nurture cross-border family and commercial ties. The risks from these contacts are not uniform for Brazil’s neighbors. In southern Brazil, for example, the per capita infection rate is relatively low, just one in 175 in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, which borders Uruguay and Argentina. The northern states are the hardest hit. In Amapá, which borders French Guiana, one in 23 individuals has tested positive for the virus. In Roraima, which borders Venezuela and Guyana, the figure is one in 18. In Amazonas, which borders Venezuela, Colombia and Peru, and is home to Manaus, the largest city in the Amazon, one in 41 people have COVID-19. Although the region is sparsely settled, the high per capita transmission rate has worried Brazil’s neighbors to the north and west, given the region’s limited resources and vulnerable populations, including indigenous communities.

Cross-Border Contagion

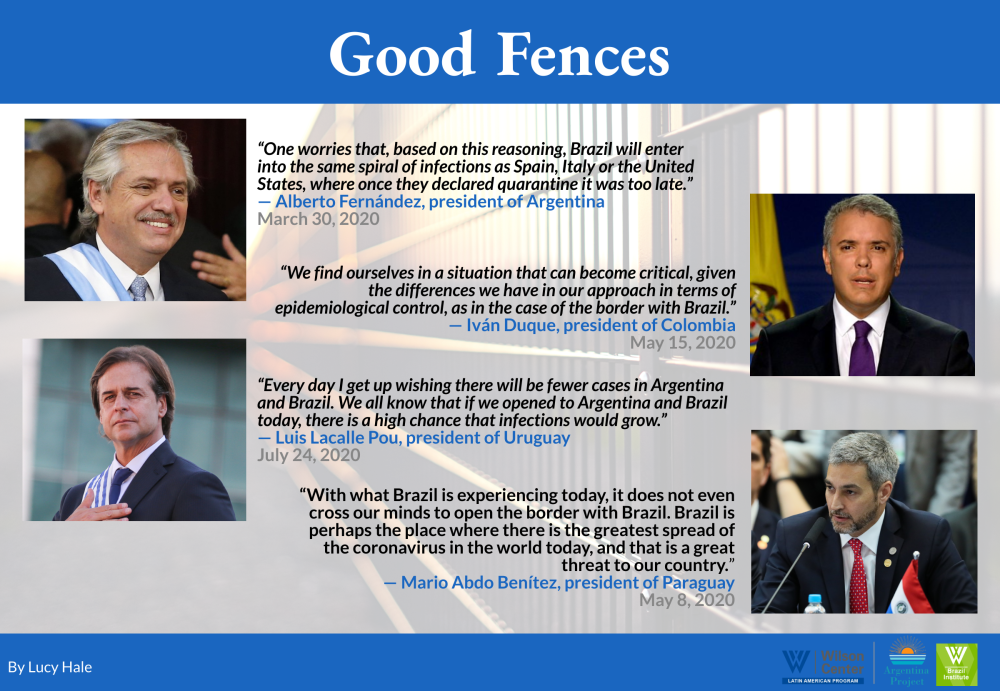

In response, Brazil’s neighbors have taken steps to contain cross-border spread of the disease. Paraguay and Uruguay have closed their borders to Brazil, with Paraguayan officials calling Brazil’s response “chaotic,” and the head of the Paraguayan Health Surveillance Board suggesting Paraguay will not reopen the border until “the wave in Brazil is over.” (“If Brazil sneezes, Paraguay will have pneumonia,” one Paraguayan official said.) In Argentina, President Alberto Fernández said, “Brazil worries me a lot,” and warned of travel to Argentina from São Paulo, “where the infection rate is extremely high, and it doesn’t appear to me that the Brazilian government is taking it with the seriousness that it requires.” The Brazil-Venezuela border was one of the first to shut down. More recently, French Guiana closed its borders to Brazil, after cases began appearing in Saint-Georges, whose population is 40 percent Brazilian.

Nevertheless, there is evidence of cross-border contagion. Tellingly, one of the COVID-19 hotspots in Colombia is Leticia, on the border with Brazil. Colombian Health Minister Fernando Ruiz explicitly attributed the outbreak in Leticia to contagion from Brazil, complaining that Colombia and Brazil have failed to follow “a common strategy, with quarantine and testing, to contain the spread of the disease where we share borders,” a result of turnover at Brazil’s Health Ministry and Brazil’s general lack of urgency to contain the virus. Indeed, the Pan American Health Organization has warned of a “concerning trend towards high transmission in border areas.”

Do Us Part

Before the pandemic, Uruguay and Paraguay were the countries with the deepest economic and cultural ties with Brazil. For both, Brazil is the second-largest export market. In border cities, citizens of both countries work and transit frequently. But Brazil’s uncontrolled COVID-19 outbreak has forced authorities in Uruguay and Paraguay to impose border controls, disrupting commercial and social ties. For public health authorities in both countries, who have so far successfully slowed the virus’s spread, the porous border with Brazil is a weak link. As one Uruguayan health expert observed, “Brazil is the great sword of Damocles hanging over our heads.”

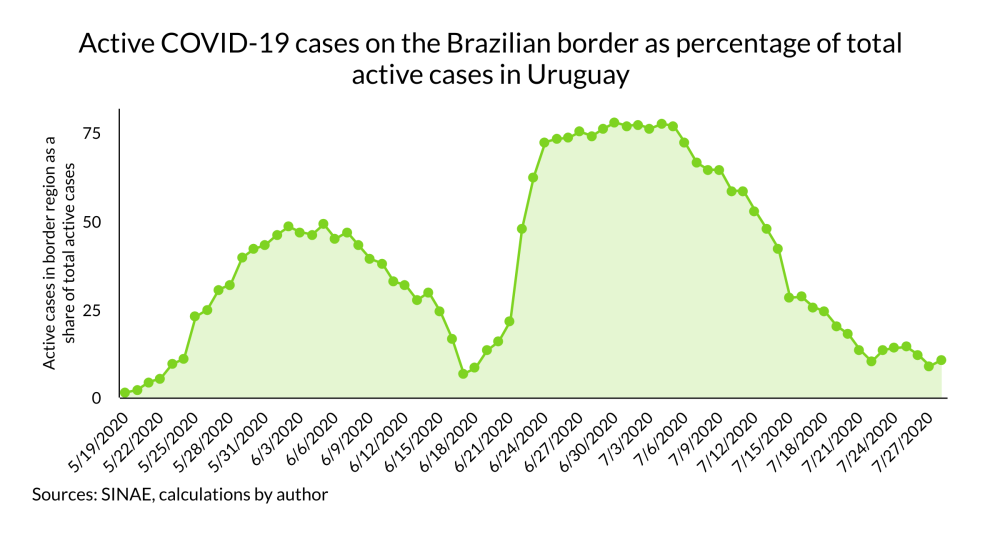

In Uruguay, border controls have sharply reduced the number of crossings from about a million in January to 21,000 between March and June. In shared border towns such as Rivera, where separation is not feasible, Uruguayan and Brazilian authorities have negotiated common pandemic policies. Uruguayan President Luis Lacalle Pou and Mr. Bolsonaro established the first bilateral commission in the region to combat the spread of COVID-19. Nevertheless, there have been at least three outbreaks at the Uruguayan border, a region that accounts for 60 percent of Uruguay’s coronavirus cases. Most Brazilians entering Uruguay now must show a negative COVID-19 test conducted at least 72 hours before entry.

Paraguay’s approach to the border is even tougher. In March, President Mario Abdo Benítez closed all border crossings and imposed one of the region’s strictest quarantines. Four months later, only Paraguayan nationals are admitted into the country, where they spend two weeks in quarantine in a government isolation center. The government has no plans to reopen. The authorities are particularly concerned about Foz de Iguazú, which poses a risk to Paraguay’s Ciudad del Este. Brazil, Mr. Abdo Benítez said, is a “great threat.”

For Argentina, political tensions between Mr. Fernández and Mr. Bolsonaro had already begun to divide South America’s largest nations before the coronavirus. But the pandemic has sped the separation.

Time magazine recognized Argentina’s coronavirus response as among the best in the world, highlighting its prompt and strict national quarantine, imposed March 20 and still in effect. Argentina’s population is twice that of neighboring Chile, but it has registered fewer than 174,000 cases compared to nearly 350,000 across the Andes. The uncontrolled spread in Brazil, however, is imperiling Argentina’s public health achievements.

Given the close economic ties – Brazil is Argentina’s top trading partner – their shared border is bustling despite travel limits. In an interview with the Wilson Center’s Latin American Program, Argentina’s health minister, Ginés González García, emphasized the challenges of managing Brazilian truckers. Lengthy quarantines are not feasible, so Argentina has set up special zones for Brazilian drivers to access rest rooms and unload cargo without interacting with Argentines. So far, most of Argentina’s COVID-19 cases have occurred in the capital region, but the provinces of Misiones and Corrientes are highly vulnerable, given the explosion of cases in the nearby Brazilian states of Santa Catarina, Paraná and Rio Grande do Sul. One of the few coronavirus deaths in Misiones involved a trucker who contracted the virus in São Paulo.

Coordination is also a challenge. Brazil is on its third health minister during the pandemic. Meanwhile, the shared public health threat has not eased tensions between Fernández, a Peronist, and his far-right counterpart in Brazil, whose starkly divergent approaches to COVID-19 is one of several policy disputes, including conflicting visions on free trade.

Good Fences

For Colombia, the border with Venezuela had long been the biggest policy challenge. But now, three states in southern Colombia that border Brazil are some of the hardest hit by the coronavirus: Amazonas, Guainía and Vaupés are majority indigenous, and although together they account for less than 0.004 percent of the country’s population, by mid-July they had registered 1.6 percent of Colombia’s coronavirus cases, the highest per capita rate in Colombia. On July 24, the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia reported that the number of indigenous people infected with the coronavirus was doubling every nine days, affecting 61 different indigenous groups. It called the situation “tragic,” and linked the “high level of vulnerability” to the precarious health conditions that have historically affected indigenous territories.

While five Colombian cities – Bogotá, Barranquilla, Cali, Cartagena and Soledad (Atlántico) – account for over 62 percent of COVID-19 cases, Leticia, the capital of Amazonas state on the Colombia-Brazil border, is an epicenter of COVID-19, with an infection rate 20 times that of Bogotá, the capital. In May, President Iván Duque sent troops to Leticia and other areas along the Colombia-Brazil border. But the long-standing weakness of health, energy, communications and transportation infrastructure has made the outbreak difficult to contain. In late July, UN offices in Brazil, Colombia and Peru issued an “urgent call” for greater international assistance for indigenous communities living along the Amazon River bordering all three countries.

Authors

Senior Director, Albright Stonebridge Group

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Brazil Institute

The Brazil Institute—the only country-specific policy institution focused on Brazil in Washington—aims to deepen understanding of Brazil’s complex landscape and strengthen relations between Brazilian and US institutions across all sectors. Read more

Explore More in Weekly Asado

Browse Weekly Asado

Dengue Haunts South America’s Summers

Lessons from Costa Rica’s Economic Transformation

Women and Latin America’s Digital Revolution