A blog of the Kennan Institute

BY LUCIAN KIM

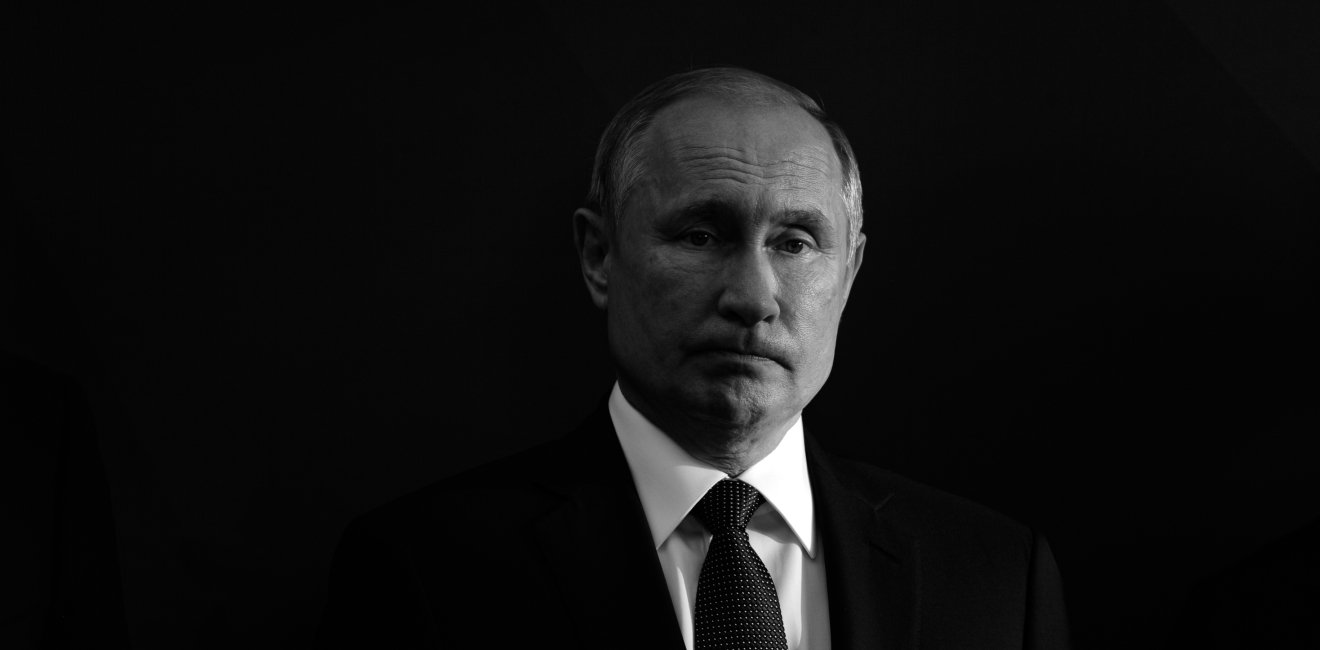

Vladimir Putin has a dangerous hobby.

His obsession with the past and his historical legacy is consuming thousands of lives, wreaking destruction on Ukraine and threatening Russia’s own future.

In Ukraine, Putin is fighting to restore his version of historical justice and to make 2022 a new milestone in world history, on par with the end of World War II in 1945 or the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. But because his grasp of history is highly selective and distorted by politics, Putin’s attempt to reorder the world is doomed to failure, and his only sure legacy is a place in the rogues’ gallery of history’s villains.

In the leadup to his renewed attack on Ukraine, Putin laid out the justification for all-out war in a rambling, one-hour televised speech that started like a history lesson.

“Ukraine is not just a neighboring country for us. It is an inalienable part of our own history, culture and spiritual space,” he said. According to Putin, modern Ukraine was a creation of Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin that included “historically Russian land.”

Putin was rehashing 5,000-word treatise he had published over the summer with the ominous title “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians.” In it, he claimed that Russians and Ukrainians were “one people,” and that the West was busy turning Ukraine into an “anti-Russia.”

Ironically, Putin has done more than any recent Kremlin ruler to drive Ukraine toward the West and foster animosity among Ukrainians. Before Putin’s first unprovoked invasion in 2014, most Ukrainians viewed Russia positively and were largely ambivalent about NATO membership. But after Putin occupied Crimea and instigated a bloody insurgency in eastern Ukraine, Ukrainians naturally began to view Russia as an enemy and to see NATO membership as a sensible goal.

Kyiv, not Moscow, is the cradle of the eastern Slavic civilization shared by present-day Ukrainians and Russians. Putin appropriated parts of this common history to justify his annexation of Crimea, where a medieval Kyivan ruler named Vladimir I—Volodymyr I, in Ukrainian—converted to Christianity in the tenth century. In Kyiv, a hilltop statue of Prince Volodymyr has been one of the city’s beloved symbols for more than 150 years. In 2016, Putin erected his own gargantuan statue of Prince Vladimir just outside the Kremlin walls.

The Kremlin’s TV channels put out the message that everything Russians and Ukrainians have in common proves they are one people, while all attempts by Ukrainians to assert their identity are evidence of Western interference or outright fascism. Ukraine is a failing state, Kremlin propaganda says, and the United States and its allies are interested only in using the country as a staging ground to attack their real target, Russia.

Putin’s certainty that the West won’t come to Ukraine’s defense militarily has untied his hands to unleash deadly, blunt force against his neighbor. Putin equates the struggle for Ukraine with the survival of his regime, and he is showing that no amount of blood and treasure is too dear a price to pay.

Putin seems to have internalized the words of former U.S. national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, who once wrote that “without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be a Eurasian empire.” With its rich agricultural lands and heavy industry, Ukraine was the jewel in the crown of the Russian Empire and later the Soviet Union. Strategically, control of Ukraine allowed Russia to project power across the Black Sea and deep into Europe.

In 2005, Putin famously called the collapse of the Soviet Union the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe” of the twentieth century. His choice of words is revealing. Despite the untold suffering that Nazi Germany had inflicted on the peoples of the Soviet Union, World War II ended in a geopolitical victory for Stalin, whose new empire stretched from Prague to Pyongyang, the absolute zenith of Russian power. For Putin, the breakup of the Soviet Union meant the loss not only of half of Europe but of territories that, after centuries of domination, many Russians had come to see as part of their empire’s heartland.

In the absence of any unifying national idea, Putin chose the Soviet Union’s “great victory” in World War II to rally Russians, holding ever bigger military parades on Red Square to mark the occasion. He turned Russians’ painful memories of World War II into a war cult that is now being mobilized to fight “Nazis” in Ukraine.

Putin’s glorification of the Red Army has made it impossible for Russia to reconcile with its central and eastern European neighbors, which became captive nations in the aftermath of the war. The Kremlin has denounced criticism of the Soviet Union during World War II as the “falsification” of history, stifling an honest reckoning with Stalin’s collusion with Hitler before the Nazi invasion. In December, Russian authorities shut down Memorial, the human rights group dedicated to uncovering the Soviet state’s crimes and preserving the memory of its victims.

If Russians are not allowed to condemn past crimes committed in their name, they will not be able to liberate themselves from the Soviet mindset. And as long as they are not free of the Soviet past, Russians will be unable to accept the paradox that the Soviet Union could be both liberator and occupier of half of Europe—and that they themselves were prisoners in their own country.

In an address to the nation on the first day of the Russian attack, Putin called Stalin’s nonaggression pact with Hitler a mistake, not because it carved up much of eastern Europe between the two dictators but because the agreement ultimately failed to ward off the Nazi invasion. This time, Putin said, Russia would not repeat the same mistake and had no choice but to launch a preemptive strike to “demilitarize” and “denazify” Ukraine.

Putin may think that he’s refighting World War II, but his war on Ukraine is much more of a belated, bloody counterrevolution against the wave of pro-democracy protests he witnessed as a KGB officer in East Germany three decades ago. The velvet revolutions in Prague and East Berlin heralded the end of the Soviet empire.

In 2004, Ukraine experienced its own people-power revolt in the form of the Orange Revolution, and in 2011, mass protests began in Moscow in what would become the greatest challenge to Putin’s rule. After Ukrainians took to the streets once again in 2013–2014 to protest their Kremlin-backed leader, Putin seized Crimea as a first step to stopping Ukraine’s westward drift once and for all.

For Putin, the entire post–Cold War era has been a period of Russia’s humiliation at the hands of a hostile and jeering West. His all-out war on Ukraine is as much meant to punish Ukrainians for choosing their own destiny as it is to avenge perceived indignities by former rivals. Putin uses the vocabulary of past U.S. conflicts, justifying his actions in Ukraine with unfounded accusations of “genocide” of ethnic Russians or Ukraine’s development of “weapons of mass destruction.” Putin is exacting revenge for the time when Russia had to watch helplessly while the United States went to war despite the objections of the Kremlin.

The entire Ukrainian nation has become collateral damage in Putin’s last-ditch effort to bring back Russia’s greatness. Putin has staked all his bets on hard power alone. Even the Soviet Union had an ideology with global appeal, but Putin’s Russia has nothing to offer other countries, not even petrodollars.

Less than a month before attacking Ukraine, Putin laid a wreath at a memorial dedicated to the hundreds of thousands of victims of Nazi Germany’s savage siege of Leningrad during World War II.

Now it is Putin who is besieging cities in Ukraine.

The similarities with World War II are clear—just not the way Putin imagines them.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.

Author

International Crisis Group

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Wilson Center is proud of its historic connection to the Kennan Institute and looks forward to supporting its activities as an independent center of knowledge. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in The Russia File

Browse The Russia File

Chechnya as a Model of Modern Russia

Russia’s Indigenous Communities and the War in Ukraine

Gas and Power in a Changing US–Russia Relationship