A blog of the Latin America Program

Unsocial Networks

Gonzalo Baeza // Flickr

Unsocial Networks

What went wrong? WhatsApp, a messaging application owned by Facebook, is immensely popular in South America, with over 130 million Brazilians users. In last year’s presidential election, its popularity made it an ideal platform to spread false and misleading information. Marketers culled phone numbers from Facebook and added them to WhatsApp groups. They then sent out targeted messages, largely to smear Jair Bolsonaro’s opponent, Fernando Haddad of the Workers’ Party. As many as 86 percent of voters received fake news during the campaign.

What did WhatsApp have to say? Last July, to stop the spread of misinformation, WhatsApp restricted the number of times a message could be forwarded. For example, in India, the platform’s largest market, WhatsApp imposed a five-recipient limit on forwarded messages, while globally it limited forwards to 20 recipients. However, WhatsApp’s end-to-end encryption protects user data, making it a challenge to identify individuals spreading misleading information and track their messages.

Did WhatsApp do better for India’s spring elections? India’s elections, held during April and May, were a major test of WhatsApp’s lessons learned from the Brazil mishap. A staggering 200 million Indians use WhatsApp – about 15 percent of the population. After a WhatsApp message containing false information resulted in twenty lynchings last year, WhatsApp restricted the number forwards users can send. For the elections, WhatsApp created a tip line for Indian users to determine the veracity of messages. Despite these efforts, India’s elections still suffered from widespread disinformation campaigns. In all, fake news circulation spiked during the elections by an estimated 40 percent, though WhatsApp reportedly shut down400,000 accounts each month in the run-up to the election.

What’s at stake for Argentina and Uruguay? Given the popularity of WhatsApp, there is significant concern about the app’s (mis)use in the upcoming Argentine and Uruguayan presidential elections. The app has 40 million users in Argentina (91 percent of the country’s Internet users) and 2.7 million in Uruguay (78 percent of the wired population). As in Brazil, many Argentines get their news from social media. Yetmany voters are unfamiliar with fake news and bots, and may not research outlandish stories before they vote – despite Argentina’s groundbreaking fact-checking organization, Chequeado. Already in Uruguay, one failed primary candidate, Juan Sartori, of the Partido Nacional, is accused of spreading misinformation on WhatsApp during his campaign.

A glimmer of hope? To combat fake news and misinformation, representatives of Argentina’s political parties convened May 30 to negotiate an informal agreement on the responsible use of social networks and digital platforms in the presidential campaigns. (In March, we convened senior political figures for a workshop in Buenos Aires on the same subject, in partnership with the Annenberg Foundation Trust at Sunnylands and the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance.) However, given the polarization of Argentine politics, it is still to be seen whether this agreement effectively limits the spread of disinformation.

Why does it matter? Social media is replacing traditional information outlets, such as newspapers and television, as a source for political news. A Pew survey found that14 percent of adults in the United States have changed their views because of social media, and 20 percent of adults reported that social media swayed their opinion on a political issue or candidate in the 2016 election. As Argentina and Uruguay prepare for highly competitive presidential elections this fall, the popularity of social media platforms such as WhatsApp leave the electorates vulnerable to manipulation.

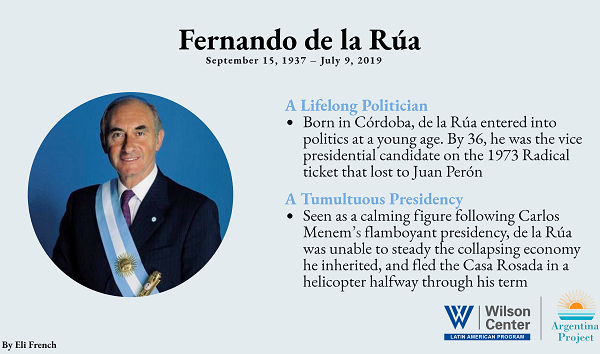

Eli French

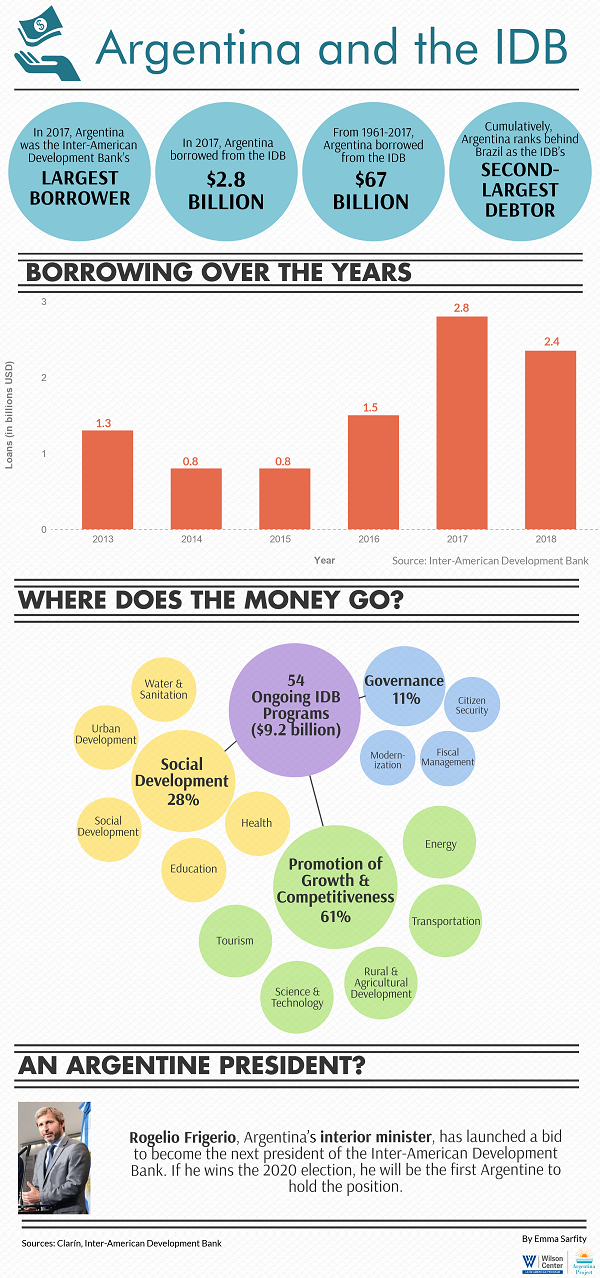

Emma Sarfity

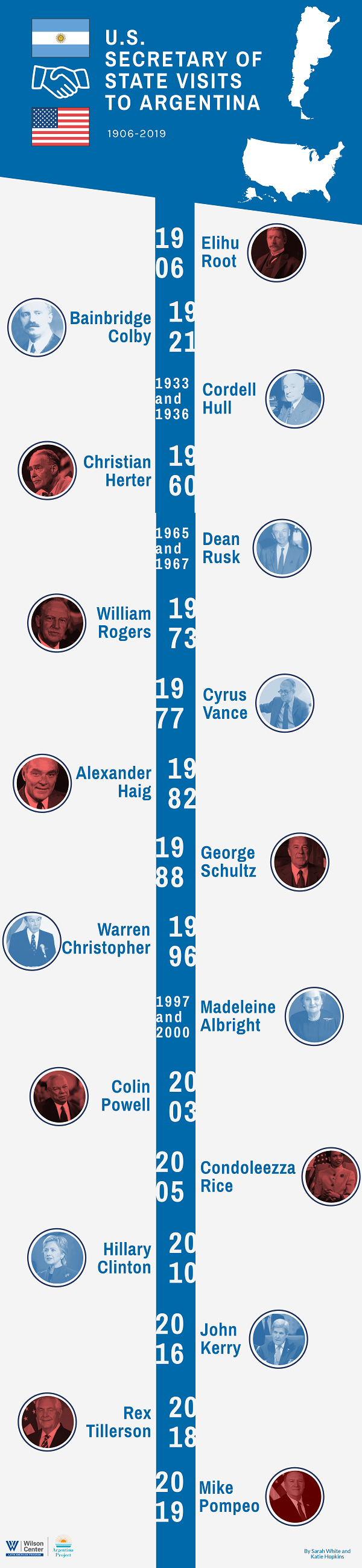

Sarah White & Katie Hopkins

Related Programs

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Argentina Project

The Argentina Project is the premier institution for policy-relevant research on politics and economics in Argentina. Read more