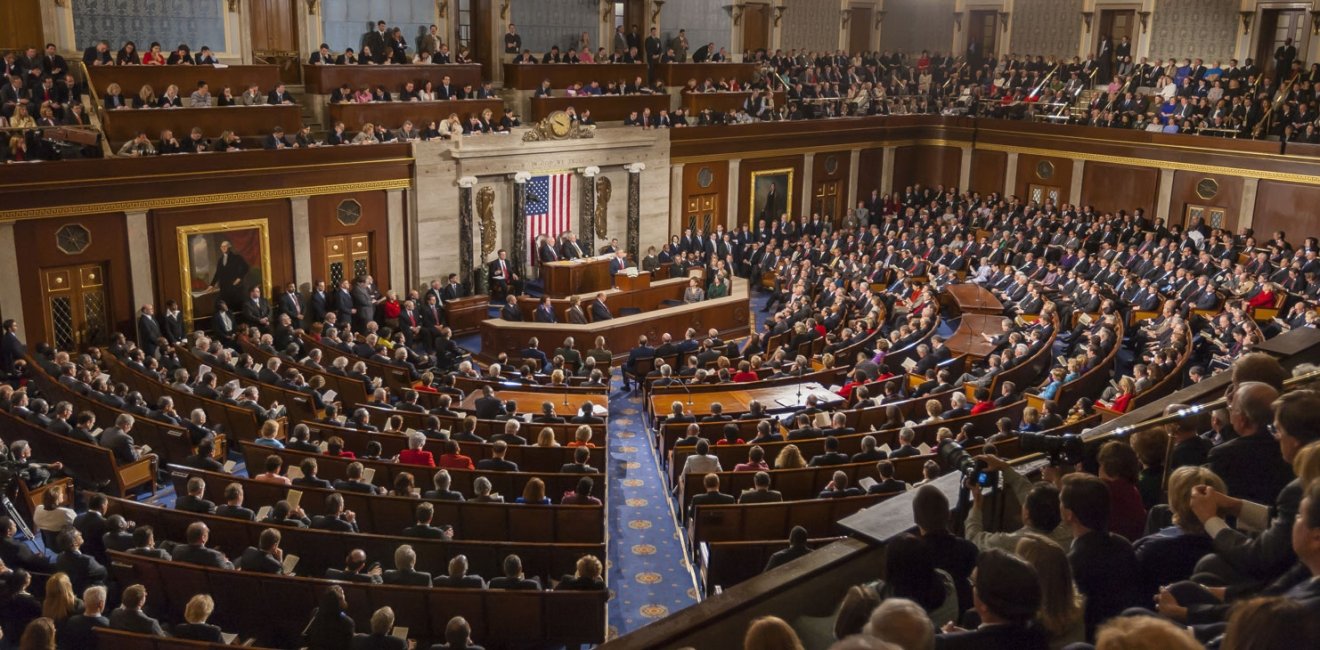

As Congress works to pass various pieces of legislation to address COVID-19, and ensuing economic downturn, revisiting national emergencies of the past can illustrate Congress’ patterns during trying times.

Historically, when a major crisis arises, Congress comes to bipartisan agreements. Partisan quibbles are set aside, and collaborative work creates legislation during catastrophes. Yet these agreements often lead to divisions between Democrats and Republicans once the dust settles. After a crisis, legislation that once passed in a bipartisan way is usually no longer popular with legislators in both parties.

In October of 2001, just weeks after the 9/11 attacks, Congress passed the Patriot Act. This legislation to improve the U.S. government’s response to deter and detect terrorism was approved by overwhelmingly bipartisan margins, despite concerns over civil liberties and government intervention in privacy. In the Senate, the Patriot Act passed 98-1.

Despite a lack of comfort about the legislation, both Democrats and Republicans felt that they needed to act immediately in the face of the crisis. The Patriot Act passed easily because a collective sense of urgency overrode the policy’s intricacies, but Congress did give the provision a time limit.

Senator Ron Wyden, a Democrat from Oregon, fought for the law to have a five-year sunset provision –forcing Congress to actively take up the law again in order for it to remain in place. “These provisions would be more thoughtfully debated at a later, less panicked time,” Wyden said.

Five years later, as the law was about to expire, there was less agreement between parties when Congress took up the measure again. The hysteria following the attacks had subdued, and the passage of time left room for new debates and divisions.

In late 2005 – only weeks before the deadline for the Patriot Act to be reauthorized – Senator Russ Feingold organized a bipartisan group of senators to block a long-term reauthorization of the Patriot Act, and instead, extended it for just six months. This extension was to provide critics more time to debate provisions of the act without having the act expire entirely.

Six months later, Feingold led a filibuster on the Senate floor, arguing for changes to provisions involving government surveillance on Americans. Despite the Senator’s attempts, the act eventually passed with slight modifications over civil liberties that appeased many Senate Republicans in Feingold’s bipartisan coalition. President Bush praised the Senate for “overcoming the partisan attempts to block its passage.”

The fight over the Patriot Act continued into 2015 when Congress failed to come to an agreement, and the act expired in May. A day later, Congress replaced parts of the Patriot Act with the USA Freedom Act, addressing the previously controversial provisions over government surveillance. While the Patriot Act was initially passed swiftly, Congress was not able to continue their bipartisanship years down the road. As policies began to play out in real-time, the opposition over the provisions grew stronger.

The Patriot Act was not the only cause for contention between political parties following the 9/11 attacks. Partisanship deepened after the crisis over interventions in the economy.

The Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act (JGTRRA) was introduced in 2003 with the intention of spurring a sluggish economy in the wake of 9/11. JGTRRA was the second piece of what later became coined as the “Bush tax cuts.” The first was in 2001, just before the 9/11 attacks, and passed the Senate with 12 Democrats joining Republicans in favor. By 2003, however, the Senate was divided, and JGTRRA was tied in the Senate 50-50. The partisan battle ended with Vice President Dick Cheney's tie-breaking vote in favor of the bill's passage. Tax cuts had more significant bipartisan support prior to 9/11, but following the attacks, an invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq, and with a presidential election looming on the horizon, the divisions in Congress solidified.

The Great Recession of 2008 offers another case study in speedy bipartisan action and its subsequent breakdown. Just weeks after Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson asked Congress for legislation to solve the economic meltdown, Congress passed the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). Similar bailout legislation had failed in the House earlier, and TARP was not expected to garner bipartisan support. The crisis was deepening, and the markets had slipped lower than at the time of the first vote. Ultimately, 33 Democrats and 24 Republicans changed their minds and voted for TARP – prompted by deep-seated fears that this recession could be the new Great Depression. Somewhat unexpectedly, both parties came together in the face of an economic collapse.

Congress’ swift bipartisan action in 2008 also had little longevity. Two years later, as the country began a long period of growth after the financial crisis, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was brought to the House floor. This bill consisted of sweeping financial reform, and ultimately created a Financial Stability Oversight Council, a Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and the Office of Financial Research.

Democrats held vast majorities in Congress and the White House at that moment, and they were the main supporters of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street and Consumer Protection Act. The bill ended up passing the House along party lines, while only three Republicans joined Democrats to vote for the legislation in the Senate. The 2008 crisis brought Congress together, but the time allowed policy nuance to form and partisan cracks to harden, making bipartisan agreements far less likely.

This pendulum pattern of bipartisanship is not just a feature of the twenty-first century. When President Franklin Roosevelt was elected in 1932 amid the Great Depression, Congress worked together to pass a series of programs as part of the New Deal. Many progressive Republicans were in support of targeted legislation that would secure the rights of workers to earn better wages, hours, and working conditions. One of the most enduring pieces of legislation to come out of the New Deal was the Social Security Act of 1935. A vast majority of Republicans in both the House and the Senate voted for this legislation.

However, when a recession hit in May of 1937, President Roosevelt began to lose favor among both the conservative wing of his own party and Republicans in the opposing party. During the 1938 midterm elections, Roosevelt’s attempts to campaign against conservative congressional Democrats in the primary failed. After the election, conservative Democrats band together with Republicans to win 80 new seats in the House and the Senate. With a portion of Democrats and Republicans voting together, many of Roosevelt’s proposals were defeated, and the bipartisan battle against the Great Depression ended.

As the U.S. finds itself in the middle of a public health emergency caused by the novel coronavirus pandemic, and a swift economic downturn as the nation battles to halt it, Congress has felt a lot of pressure to act swiftly to provide relief to hospitals, families, and businesses that are experiencing direct effects of this crisis. As it did after 9/11, in the Great Recession and during the Great Depression, Congress rid itself of partisan divisions during a catastrophe and worked together on legislation. Yet history tells Americans to expect that the “crisis” bipartisanship of this moment is unlikely to continue into the future.

Author

Congressional Relations

The Wilson Center’s office of Congressional Relations works to maintain a vibrant relationship with Members of Congress and their staffs. We organize and run a series of educational programs led by Wilson Center experts, ranging from seminars to private briefings, with the purpose of increasing congressional staffers’ knowledge of foreign policy. We also coordinate outreach to Capitol Hill, including testimonies by Wilson Center scholars and briefings specifically for Members of Congress. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Hitting the Reset Button in the Indo-Pacific

How Carbon Measurement Can Benefit America